47,300 Gigawatt-Miles From Nowhere

The NY Times and DOE use a silly metric to promote an impossible-to-achieve expansion of the electric grid.

H.L. Mencken, the dyspeptic journalist and literary critic who had his heyday in Baltimore about a century ago, coined several memorable lines. Among his most enduring: “For every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong.”

Mencken’s line came to mind after reading an editorial in the New York Times called “We Desperately Need a New Power Grid. Here’s How to Make It Happen.” The piece began: “To tap the potential of renewable energy, the United States needs to dramatically expand the electric grid between places with abundant wind and sunshine and places where people live and work. And it needs to happen fast...without new power lines, much of that electricity will continue to be generated by burning carbon.”

It cites a report published by the Department of Energy in February — the “National Transmission Needs Study” — which says the U.S. needs to build 47,300 gigawatt-miles of new power lines by 2035. That would, according to the agency, expand the existing transmission grid by 57%. The Times’ editorial writers claim that this build out can be fostered by putting “a single federal agency in charge of major transmission projects.” That agency, of course, is the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. The editorial then cites a bill introduced in March by Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) and Rep. Mike Quigley (D-IL) that would create a new siting authority within FERC that would “ease” the regulatory process of building new transmission. The Times claims that “shifting decision-making from state and local governments to the federal government would create a single, national forum in which policymakers can weigh the costs and benefits of power projects.”

There’s the “clear, simple, and wrong answer” that Mencken was referring to. Putting FERC in charge of our sprawling electric grid — a network that was constructed over multiple decades — won’t result in the quick construction of tens of thousands of miles of high-voltage transmission lines in less than a dozen years.

The Times’ editorial didn’t include any reference points that put the scale of the challenge — and in particular, how many miles of transmission have been built in recent years — into context. Nor did it mention the vast amounts of steel, copper, wire, and electric transformers that would be needed. Instead, it claimed the U.S. should embark on a massive expansion of the high-voltage grid because, well, you know, renewables and climate change.

“Streamlining regulation to accelerate renewable energy development is a plan that both parties can embrace,” claimed the Times. It went on, saying the U.S. needs “a plan to build a new electric grid,” and “without decisive action” Congress and the Biden administration will “waste a precious chance to limit climate change.”

Try as they might, the Times and the DOE cannot wish away the physical limits of the sprawling network they so desperately want to expand. Their wished-for expansion won’t happen because it can’t happen. I’ll explain why it can’t happen by looking at three things: the historical rate of grid expansion (and that silly gigawatt-mile metric), supply chain constraints, and the lack of skilled labor (read: electric linemen).

Let’s take those in order.

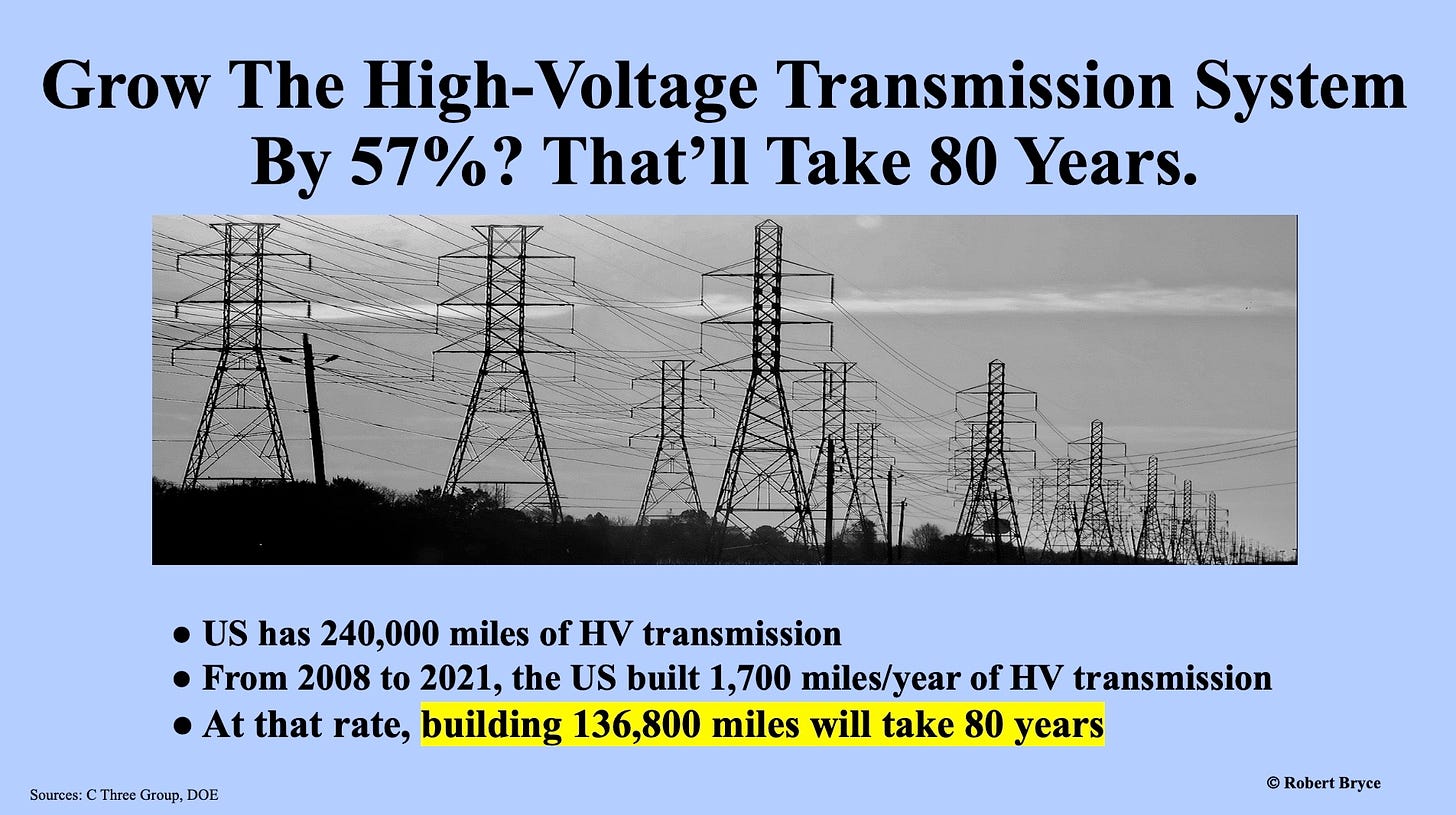

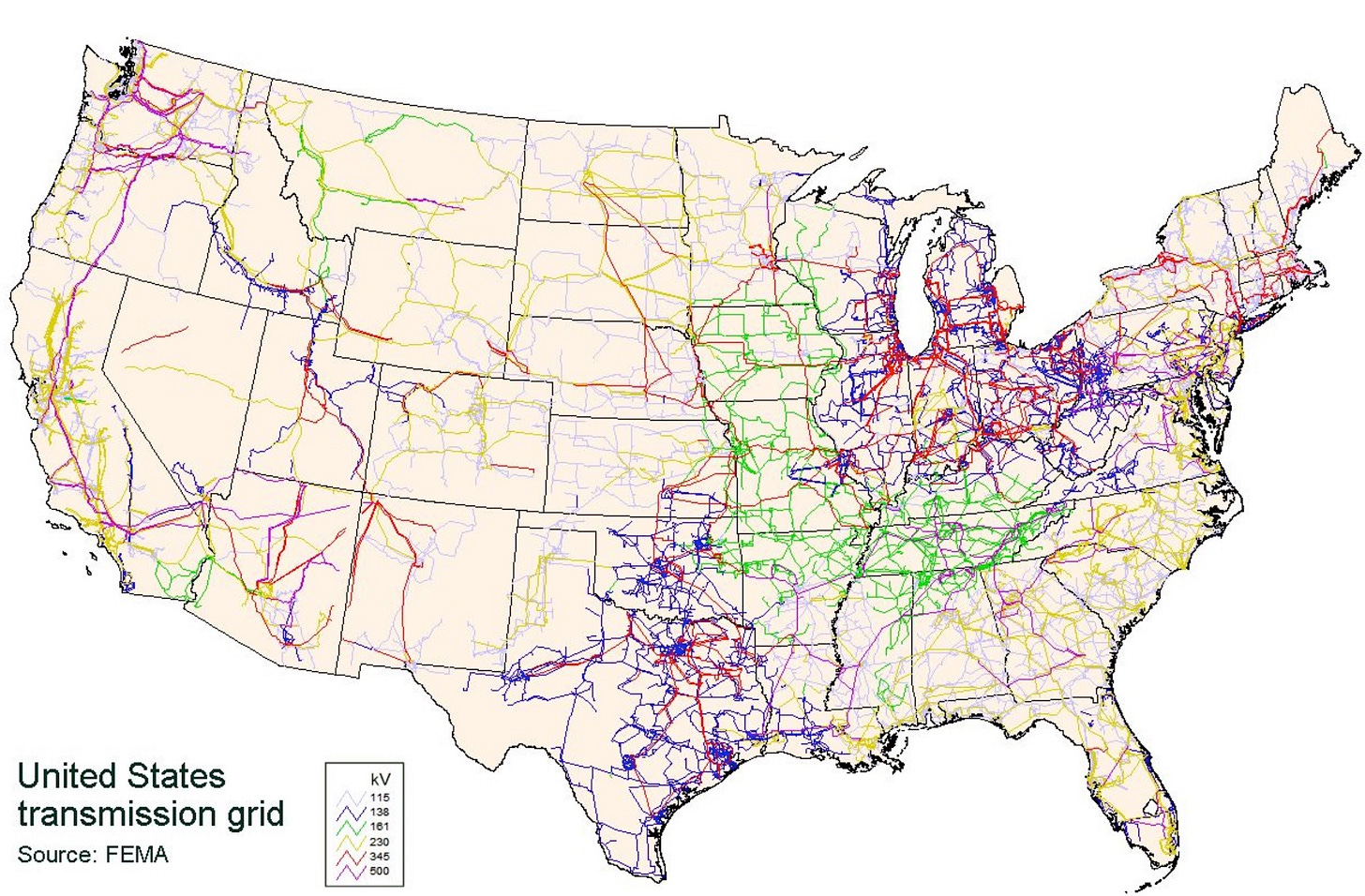

As I reported in these pages in February, in “Out of Transmission” our high-voltage power system has been growing very slowly over the past few years for many reasons including land-use conflicts and permitting challenges at the local, state, and federal levels. Since 2008, according to data from the C Three Group, the U.S. has been adding an average of just 1,700 miles of HV transmission (230 kV and above) per year.

The Times and DOE claim we need 47,300 miles of new transmission lines by 2035. But they have muddied the waters by using a bastard metric — gigawatt-miles — which the agency notes “is a convenient unit for capacity expansion models but is not a common practice in industry.” There’s an understatement. Mixing SI units and imperial units is a no-no. (Gigawatt-miles is akin to saying something like “liter-inches.”) The DOE’s report includes an explanation (page 88) of how to convert the capacities of varying powerlines (230kV, 345 kV) into gigawatt-miles. But the explanation is impenetrable gobbledygook that contains an obvious typo. Furthermore, on the very same page, the agency introduces yet another bastard — terawatt-miles — which makes their calculations even more confusing.

In trying to track the metric down, I searched for technical papers or references that used gigawatt-miles as a metric and were published before the DOE report. I got only two hits. Surely artificial intelligence could help me. So I asked ChatGPT: “What is a gigawatt-mile?” The AI oracle replied: “I apologize, but it seems that ‘gigawatt-mile’ is not a commonly used unit of measurement or a well-defined term. It could potentially be a combination of two separate units, gigawatts and miles, but without further context or clarification, it is difficult to provide a specific meaning for the term.”

I asked ChatGPT: “What is a gigawatt-mile?” The AI oracle replied: “I apologize, but it seems that ‘gigawatt-mile’ is not a commonly used unit of measurement or a well-defined term. It could potentially be a combination of two separate units, gigawatts and miles, but without further context or clarification, it is difficult to provide a specific meaning for the term.”

So let’s ignore the phony-baloney gigawatt-mile metric and use real numbers. The U.S. has about 240,000 miles of high-voltage transmission lines. A 57% increase in the size of that network would require building 136,800 miles of new lines. Thus, at the current rate of expansion (1,700 miles per year), it will take 80 years to achieve the target being promoted by the Times and DOE.

In addition to the permitting and land-use issues, any major expansion of the grid will have to grapple with the global supply-chain crunch, including the ongoing shortage of electric transformers, an issue I covered in a March 31 piece, called “Untransformed.” Delivery times for distribution transformers, like the ones you see on power poles in your neighborhood, are now a year or more. Pad-mounted transformers are also in short supply. So, too, are the large power transformers (LPTs) that will be needed to upgrade the high-voltage transmission system.

Those LPTs have repeatedly been identified as a critical weakness in the U.S. grid. A 2020 report by the Commerce Department on LPTs, (large parts of which were redacted), noted that “the U.S. market is mature, and demand for transformers is largely based on upgrades and replacements of aging infrastructure…The average transformer in the United States is 38 years old, with 70 percent of U.S. transformers older than 25 years.” In addition, the report found that the U.S. is importing about 82% of the LPTs it needs.

A 2022 DOE report said that “aging LPTs cause higher failure risk. This fact combined with challenges in the LPT supply chain and potential bottlenecks to rapid grid expansion raised concern about the vulnerability of the domestic electric infrastructure. LPTs are expensive, difficult to transport, and highly custom devices that often have long lead times.”

One of the causes of the transformer shortage is the lack of grain oriented electrical steel or GOES, a paper-thin, hard-to-manufacture metal that contains about 3% silicon by weight. Used in transformers, EVs, EV chargers, and generators, there isn’t enough GOES to go around. GOES accounts for just 1% of global steel production and wait times for some customers are now approaching a year. China, Japan, and South Korea produce more than 80% of the world’s supply of electrical steel. Only one company in the U.S., Cleveland-Cliffs, makes GOES.

This week, some of Washington’s biggest trade groups, including the National Association of Home Builders, Edison Electric Institute, American Public Power Association, National Rural Electric Cooperative Association, and the Alliance for Automotive Innovation, sent a letter to President Biden saying they are “increasingly concerned about the skyrocketing demand and limited availability of domestically produced electrical steel” and that shortages are “contributing to significant and persistent supply chain challenges across our industries.” The groups want Congress to provide more incentives for electrical steel production. They also asked for an electrical steel “summit” with Biden.

The final challenge in trying to expand the electric grid may be the most difficult: finding enough skilled workers. Over the past month or so, I’ve talked to utility leaders in South Dakota, Florida, Texas, and Iowa. All of them told me the same thing: there aren’t enough linemen. One of them said that thinking we can quickly string tens of thousands of miles of new high-voltage transmission within a decade or so is “batshit crazy.”

Policymakers don’t “understand how hard it is to get a transmission project built,” said the executive, who recently retired from a large utility and asked not to be named. Even if a given project has all the permits, the utility sector doesn’t have enough linemen. “You can’t train them fast enough...It takes about seven years to train a high-voltage transmission lineman,” to the journeyman level. And as soon as lineman gets to the journeyman level, said the executive, they often leave in search of better pay.

An article published last December on Linemancentral.com, claimed there will be about 21,000 lineman job openings this year alone. The site says the labor crunch is due to three factors: baby boomers leaving the workforce, fewer people enrolling in technical and trade schools, and utilities that need more workers to help them upgrade existing transmission and distribution lines.

Pike Electric, a North Carolina-based company that does engineering, construction, and maintenance for electric utilities, is desperately short of linemen. The company’s website shows seven openings for linemen here in the Austin area. Nationwide, it has about 590 job openings, including more than 200 for linemen and workers involved in “electric overhead construction.” They also have numerous openings for field technicians, engineers, welders, mechanics, equipment operators, and truck drivers.

Jacob Williams, the CEO and general manager of the Florida Municipal Power Agency, a joint action agency that supplies electricity to 33 municipally owned utilities that serve about 4 million Floridians, told me “there aren’t enough linemen to do the basic maintenance work” that utilities have to do, much less embark on a major grid expansion. Further, he said most of the linemen “grew up on farms and ranches. They are used to working with big equipment. They don’t come from urban centers.” He continued, “You don’t just train up anybody to be a lineman.”

Before I close, a few more points. First, even if the U.S. could solve the supply chain and labor issues to expand the high-voltage system, it’s unlikely that any major expansion will happen quickly because of the diffused ownership of the American electric grid. Japan has just ten electric utilities to serve its population. France also has just ten electric utilities. The U.S. has more than 3,000 electricity providers, including investor-owned utilities, coops, publicly owned outfits like Austin Energy, as well as independent power producers, and government agencies like the Tennessee Valley Authority.

It's naïve to assume that if FERC had the authority to ease federal permitting, it could coordinate a massive buildout of the domestic grid and do so in just a decade when it will have to coordinate with so many different electricity providers. On top of that, the agency will have to deal with state utility commissions and regional transmission organizations like MISO, PJM, and ERCOT.

Second, neither the Times nor the DOE bothered to mention the staggering cost of trying to build so much transmission. But we can do some quick estimates based on the cost of projects now being proposed. The 345-kV Cardinal-Hickory Creek transmission line aims to move juice from Iowa to Wisconsin. That 102-mile project could cross the Upper Mississippi National Wildlife and Fish Refuge. It has been delayed by multiple legal challenges and is expected to cost $500 million, or roughly $5 million per mile. At that rate, building 136,800 miles of new transmission would cost about $684 billion. But with inflation raging across all utility products, including wire, transformers, and other hardware, it’s reasonable to assume the final cost will exceed $1 trillion — all of which, of course, would have to come out of ratepayers’ pockets.

The takeaway here is a point I have made before: We won’t see a massive expansion because of the physical limits on the system. Given these limits, policymakers aiming to decarbonize the electric sector should be looking at ways to utilize existing infrastructure, including wires and transformers, by building new nuclear plants on the sites where coal- or gas-fired power plants are being retired. That’s what TerraPower hopes to do in Kemmerer, Wyoming and other locations.

In short, the electric grid we have today is largely the electric grid we are going to have. We should not be spending hundreds of billions of dollars to build a grid designed to accommodate the low power density of weather-dependent renewables like wind and solar. Instead, we should be building high-power-density, weather-resilient generation that can exploit our existing grid. That, of course, means nuclear energy.

Alas, I’m not expecting to read that on the editorial page of the New York Times.

Before you go:

A hat tip to Dwight Yoakum.

If you like this piece, please hit the ♡ like button. And if you haven’t done so already, please subscribe. (And share.)

This week on the Power Hungry Podcast, I talked with Ashley Nunes of the Breakthrough Institute about EVs. Nunes made a lot of good points about why EVs won’t result in huge reductions in emissions. Check it out on my YouTube channel.

Lasch strikes again:

——

“The thinking classes are fatally removed from the physical side of life… Their only relation to productive labor is that of consumers. They have no experience of making anything substantial or enduring. They live in a world of abstractions and images, a simulated world that consists of computerized models of reality – “hyperreality,” as it’s been called – as distinguished from the palatable, immediate, physical reality inhabited by ordinary men and women. Their belief in “social construction of reality” – the central dogma of postmodernist thought – reflects the experience of living in an artificial environment from which everything that resists human control (unavoidably, everything familiar and reassuring as well) has been rigorously excluded. Control has become their obsession. In their drive to insulate themselves against risk and contingency – against the unpredictable hazards that afflict human life – the thinking classes have seceded not just from the common world around them but from reality itself.“

This is what real journalism looks like. A refreshing contrast to the pixie dust and regurgitated press releases we get from our "mainstream" media. No wonder so many Americans are so gullible.

Robert needs to appear in a nationally syndicated column.