At Fukushima Daiichi

The cleanup effort is an heroic effort and a sober reminder of the challenges facing nuclear energy.

“That crane weighs 1,260 tons,” explained Kimoto Takahiro, the deputy site superintendent at Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station who was leading our tour of the site. “It’s one of the biggest cranes in Japan.”

I have never seen a bigger crane. The machine was parked immediately west of the ruined Unit 1 reactor. It stood maybe 60 or 70 meters high. Even from our vantage point, which was about 150 meters away, I could tell that the tires on the massive machine were 3 or 4 meters tall. The back side of the crane was stacked with huge counterweights. There were probably 18 of them, neatly arranged in stacks six or seven high. The crane was being used to remove rubble from Unit 1 and to help build a new structure that would be used to remove the fuel from the ruined core of the reactor.

We were standing on a steel-lattice observation deck that Tokyo Electric Power Company had built so that visitors could see all four of the reactor buildings that had been damaged by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami. “We were prepared for a tsunami with waves of 6.1 or 6.2 meters,” Takahiro told us. “The plant got hit with a 15-meter tsunami.”

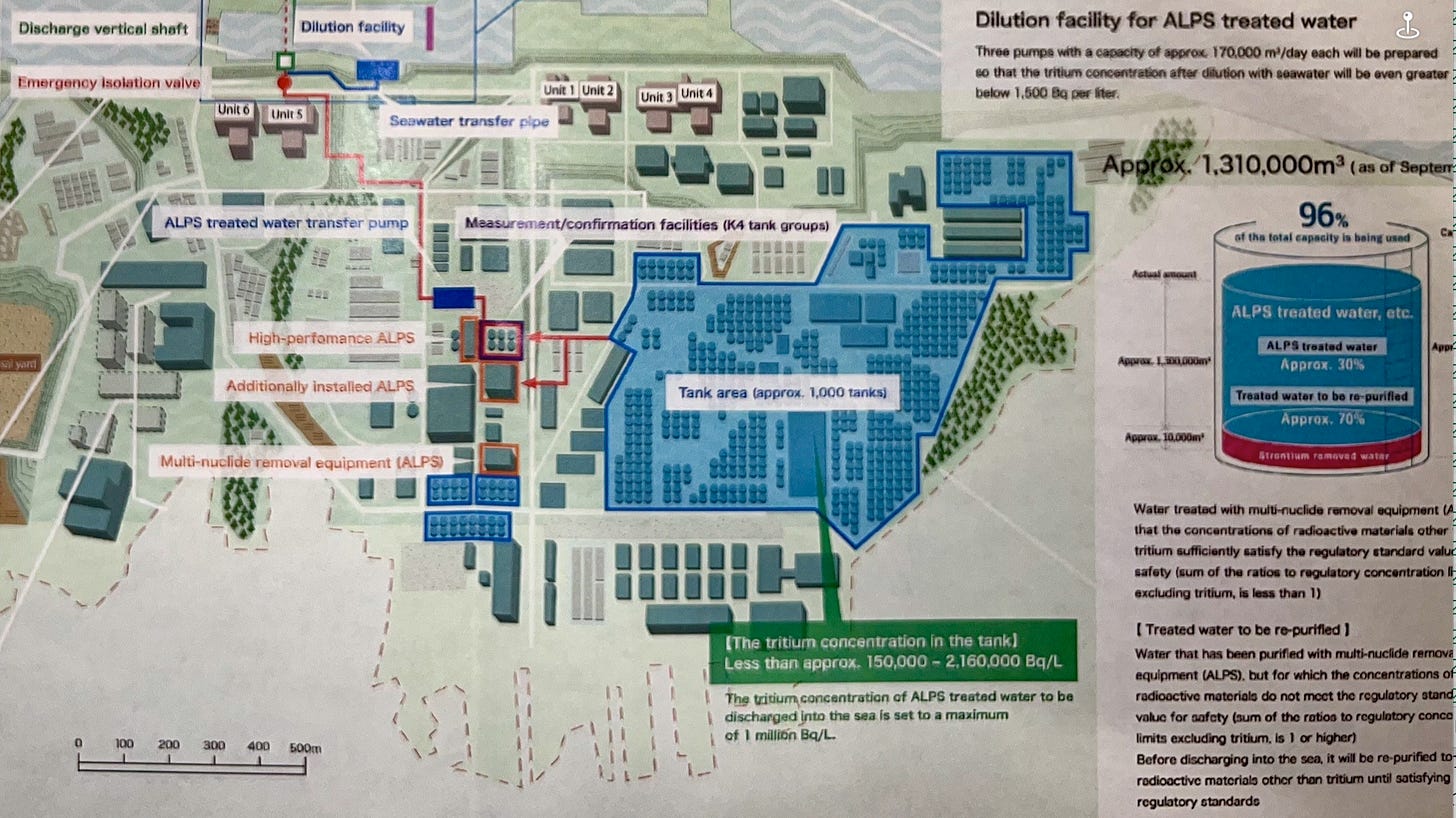

With the calm blue Pacific Ocean in front of us, it was hard to imagine such a massive wave. It was a bright, cool, and cloudless day. Evidence of the devastating accident was all around us. I knew that the cleanup and decommissioning of Fukushima Daiichi was a complex and costly project. I knew that TEPCO was spending vast sums of money on the cleanup. I knew that it was warehousing staggering volumes of water containing small amounts of tritium that it plans to begin releasing into the ocean over the next month or two. I knew that the company had constructed an ice wall that was slowing the infiltration of groundwater into the area underneath the reactors.

But knowing those facts and seeing the physical reality of what is happening in Fukushima Prefecture are two different things. We were not allowed to take photos on the property. And even if we had been, I doubt that a few snapshots would do justice to the magnitude of TEPCO’s job.

The company is storing some 1.3 million cubic meters of treated water in about 1,000 tanks on the site. But saying “1,000 tanks” is a far different thing than actually seeing them. During our one-hour bus tour through the 3.5 square kilometer (860 acre) property, we passed rows upon rows upon rows of tanks filled with water. Our stop at the observation deck was the only time we got off the bus. We got explanations about how the company is stripping contaminants out of the water and why it will be safe to discharge the treated water into the Pacific. One of the quotes that stuck in my head from the tour of the facility was made by Taminami Tatsuya, the site superintendent at Fukushima Daiichi.

He was speaking about the controversy around releasing the treated water into the sea, but he might as well have been referring to public attitudes toward nuclear energy in general. “This is not a technical issue,” Tatsuya said. “It’s a political and social issue. We have to get better public understanding to release the treated water.”

My visit to Japan––which is being sponsored by the Federation of Electric Power Companies of Japan and facilitated by Washington Policy and Analysis––has also made me understand that how we talk about nuclear energy in Japan is being contaminated by imprecise language.

We use “Fukushima” as an abbreviation for nuclear accidents in the same way we use “Chernobyl.” Yes, the damage at Fukushima Daiichi was disastrous. But the casual lumping of Fukushima with Chernobyl together ignores this key fact: no one in Japan died from radiation released by the accident at Fukushima Daiichi on 3/11. The other often-ignored fact is that about 19,000 Japanese people died from the tsunami and earthquake in the prefectures of Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima, and of that number, more than 90% of them drowned. About 40,000 evacuees lost their homes. And yet those facts, that staggering loss of life, seldom gets mentioned. Big swaths of Fukushima Prefecture have been abandoned. Empty and derelict homes and buildings were a common sight.

Yes, the disaster at the nuclear plant is important and TEPCO will be spending about $1.5 billion per year for the next 30 or 40 years to clean up the mess. But we must not forget how deadly the tsunami was and how many lives it claimed.

For more than a dozen years, I have been promoting nuclear energy as the obvious way forward if we are going to provide more electricity to the people of the world while also trying to decarbonize our economy. It is also clear that the Japanese government has taken a brave move by declaring its intent to extend the lives of its existing reactors and build new nuclear plants. Seeing what is happening at Fukushima Daiichi and the heroic effort that TEPCO has undertaken to decontaminate and decommission the plant, provided a vivid reminder of how significant Japan’s recent decision to re-embrace fission truly is and how high the stakes are for the future of nuclear energy around the world.

Visiting the plant this afternoon did not change my mind about nuclear energy. We must embrace fission. We have to make fission happen on a global scale––at the gigawatt and terawatt scales––for many reasons, including climate change. But we have to hurry up and start making and deploying the next generation of nuclear reactors that are smaller, faster, lighter, cheaper––and yes, safer––than the ones we have now. We cannot afford another disaster like the one that happened at Fukushima Daiichi.

Its amazing how the circle of life works.

Tepco screwed up and put the emergency power apparatus down beside the reactors instead of up on the hill and so they flooded, no emergency power meant kaboom.

From that Germany and others made the decision to begin closing their reactors, saying they would switch to renewables but in reality the main switch was to Russian natural gas.

And here we are in 2023.

An example of how bad situations produce bad policy.

Good work, Robert. No path to decarbonizing electricity without it without wrecking living standards and keeping 6.5 billion people from reaching ours.

Stay the course.