China Runs The Table

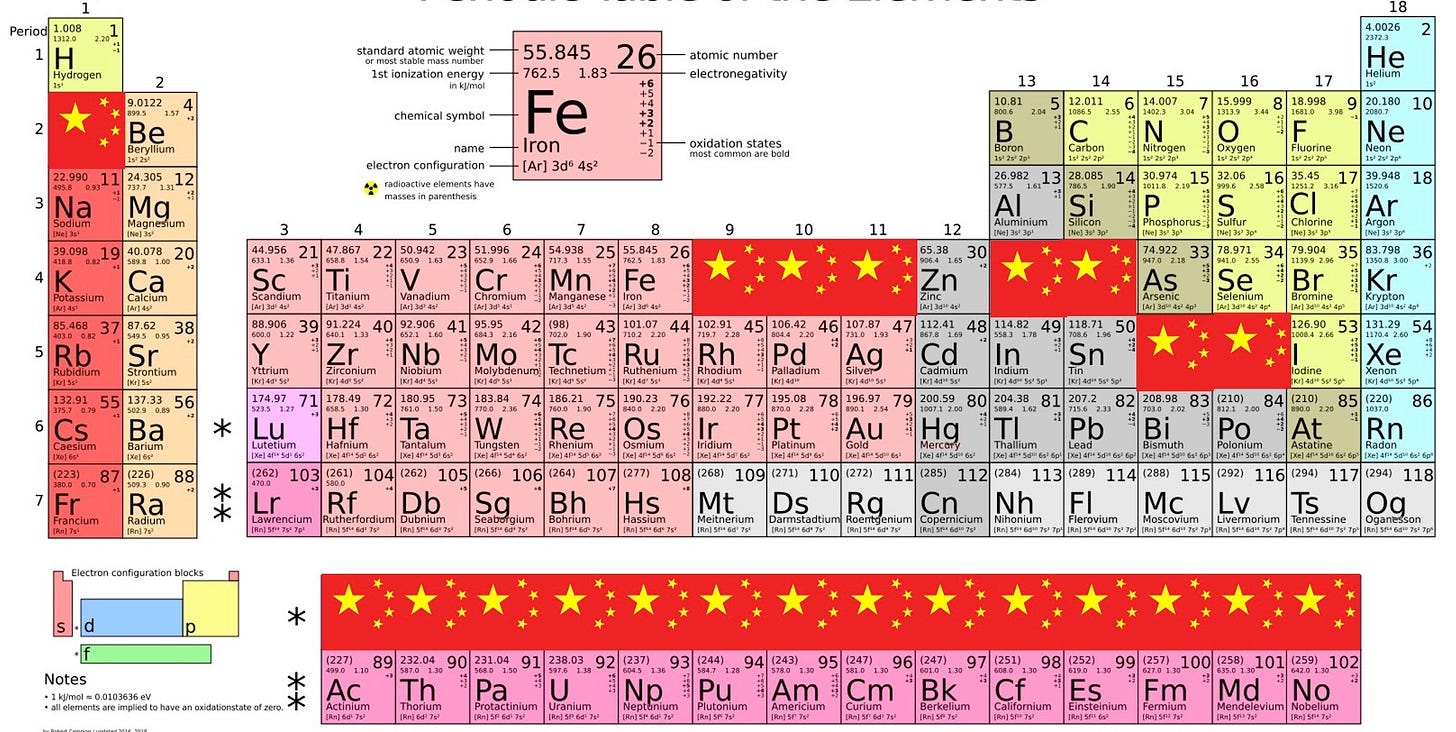

On Tuesday, Beijing banned exports of antimony, gallium, and germanium to the US. China now dominates supplies of nearly two dozen strategic elements on the Periodic Table.

On Monday, the Biden administration issued new restrictions on the export of key semiconductor equipment and software to China. On Tuesday, China retaliated by banning the export to the US of three strategic elements — antimony, gallium, and germanium — that have multiple military and civilian uses. It is also restricted the export of graphite to the US.

The two countries are now locked in a trade war over key technologies and the strategic commodities used to fabricate everything from batteries to missile guidance systems. As two analysts at the Center for Strategic and International Security put it, “critical mineral security is now intrinsically linked to the escalating trade war.” The latest salvo in the trade war provides yet another reminder that the US has, for too long, ignored its strategic vulnerability to Chinese supply chains. If China is willing to cut off the flows of antimony, gallium, germanium, and graphite to the US, it could also ban, or reduce, the exports of other strategic metals, minerals, and magnets, and, in doing so, inflict significant damage to American industry and US security.

Three decades ago, the Chinese ruler Deng Xiaoping said, “The Middle East has oil. China has rare earths. We must take full advantage of this resource.” Today, China has an effective monopoly on all of the rare earth elements and in particular, two heavy rare earths: dysprosium and terbium. It has also taken a mercantilist approach to a slew of strategic elements in the Periodic Table, including nickel, cobalt, copper, lithium, and tellurium. In addition, it has a near-monopoly on the production of neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) magnets, which are used in electric vehicles, wind turbines, and numerous consumer and military applications.

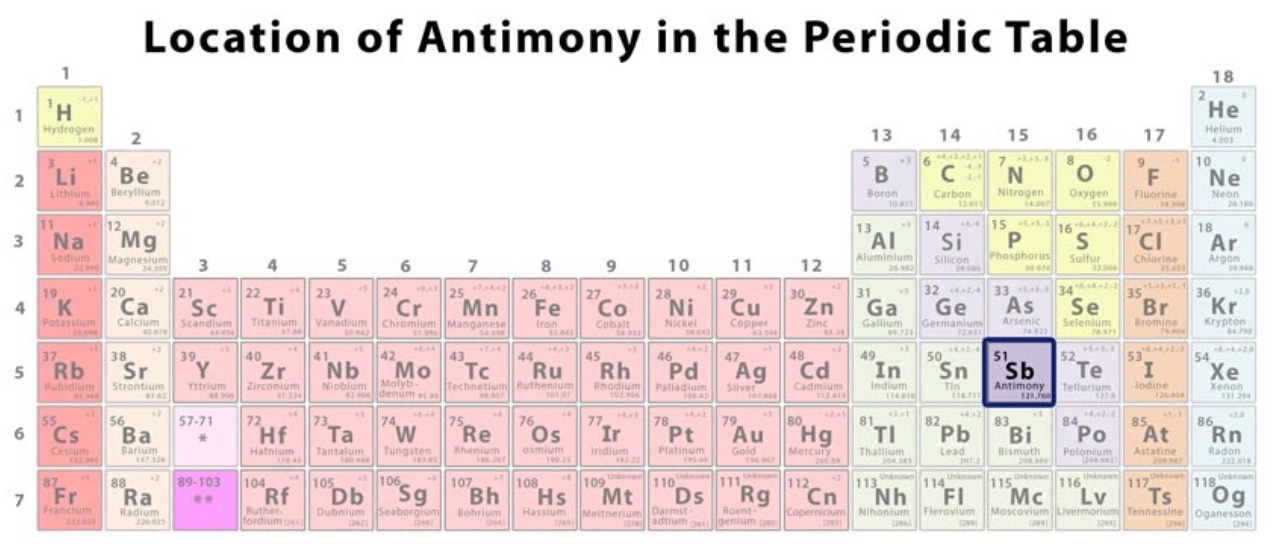

If you skipped chemistry class in high school, antimony (Sb) is one of many strategic elements in the Periodic Table, and China produces more of it than any other country. Antimony is used in lead-acid batteries to improve the strength and castability of the battery’s grids. Antimony is also critical in multiple military applications, including bullets, missiles, nuclear weapons, and night-vision goggles. On Friday, I talked to an executive at a major US manufacturer of automotive and industrial lead-acid batteries. (He asked me not to use his or his company’s name.) He said his company had secured supplies of antimony through mid-2025, but after that, “we don’t know.” He said Trump’s threat of tariffs on all Chinese goods and the looming shortage of antimony are giving him “a lot of sleepless nights.”

The executive said that prices for antimony have more than tripled over the past few weeks to $17 per pound. He said the US has taken antimony — which is considered a critical mineral by the Interior Department, along with rare earths, cobalt, and uranium — for granted for too long. The last major antimony mine in the US, the Stibnite Gold Mine in Idaho, was closed in the 1990s. Today, the US imports 100% of the antimony it needs from overseas suppliers, and China accounts for about half of that supply. Now that it has control over antimony and other key elements, the executive told me, China is “putting the screws to us.”

Can the US get unscrewed from China’s stranglehold on strategic metals and magnets? Let’s take a look.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Robert Bryce to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.