Climatism Or Energy Humanism?

Climate catastrophists claim we need to quit using hydrocarbons. These 13 charts show why we need a pro-energy, pro-human outlook

On Saturday, I gave a 10-minute TED-style talk on energy humanism to about 300 high school students. The talk was part of an all-day event at the John Cooper School in The Woodlands called the Summit for Emerging American Leaders. The event was arranged by US Rep. Dan Crenshaw, the Republican and former Navy SEAL who represents Texas House District 2. The caption for my talk is the same as the headline above. In April, I gave a similar presentation to about 50 students at Benedictine College in Atchison, Kansas.

In both lectures, I explained that today’s students are inundated with messaging about catastrophic climate change and claims that we have to quit using hydrocarbons. My aim in the presentations was simple: to remind them that regardless of what they think about climate change, energy poverty is rampant and that the real challenge we face isn’t to use less energy. Instead, it’s to make energy more affordable and more abundant so that we can continue adapting to the weather (whatever it is) and help ensure that more people all over the world — particularly women and girls — can enjoy higher living standards.

Here are some of the slides I used in the presentations.

I began with the photo above. As I explained in my latest book, A Question of Power: Electricity and the Wealth of Nations, Rehena is a resident of Majlishpukur, a tiny agricultural settlement located southeast of Kolkata. When I met her, she was 44 years old. A soft-spoken, elegant woman, she had her first child, a girl, when she was 16. Two other children, a boy and a girl, came shortly afterward. My friend, Joyashree Roy, a senior fellow at the Breakthrough Institute, explained in Bengali that we wanted to discuss electricity. Rehena replied that her modest home had been connected to the electric grid 14 years earlier. In A Question of Power, I wrote:

She immediately began talking about the difference that electricity had made to her children and their schoolwork. Thanks to electricity, her children were able to read books, practice their writing, and manage their school work at night. That had had a clear and positive result: one of her daughters was attending college in Kolkata, a fact of which Rehena was clearly proud. After we’d talked for a while longer, I asked Rehena: “If you had lived in a house that had electricity when you were growing up, would you have gone to university, too?” A brief smile flashed across her face and without a nanosecond of hesitation, she nodded her head to the right, in the way typical of many residents of West Bengal, and said, “Yes. I would have.” There was no remorse. No bragging. No what-could-have-beens in her reply. Only a direct, matter-of-fact response that was almost as if I’d asked her if the sun was going to come up in the east the next morning.

In the book, I continued:

That 15-minute conversation that I had with Rehena and Joyashree made me see the light: Darkness kills human potential. Electricity nourishes it. It is particularly nourishing for women and girls.

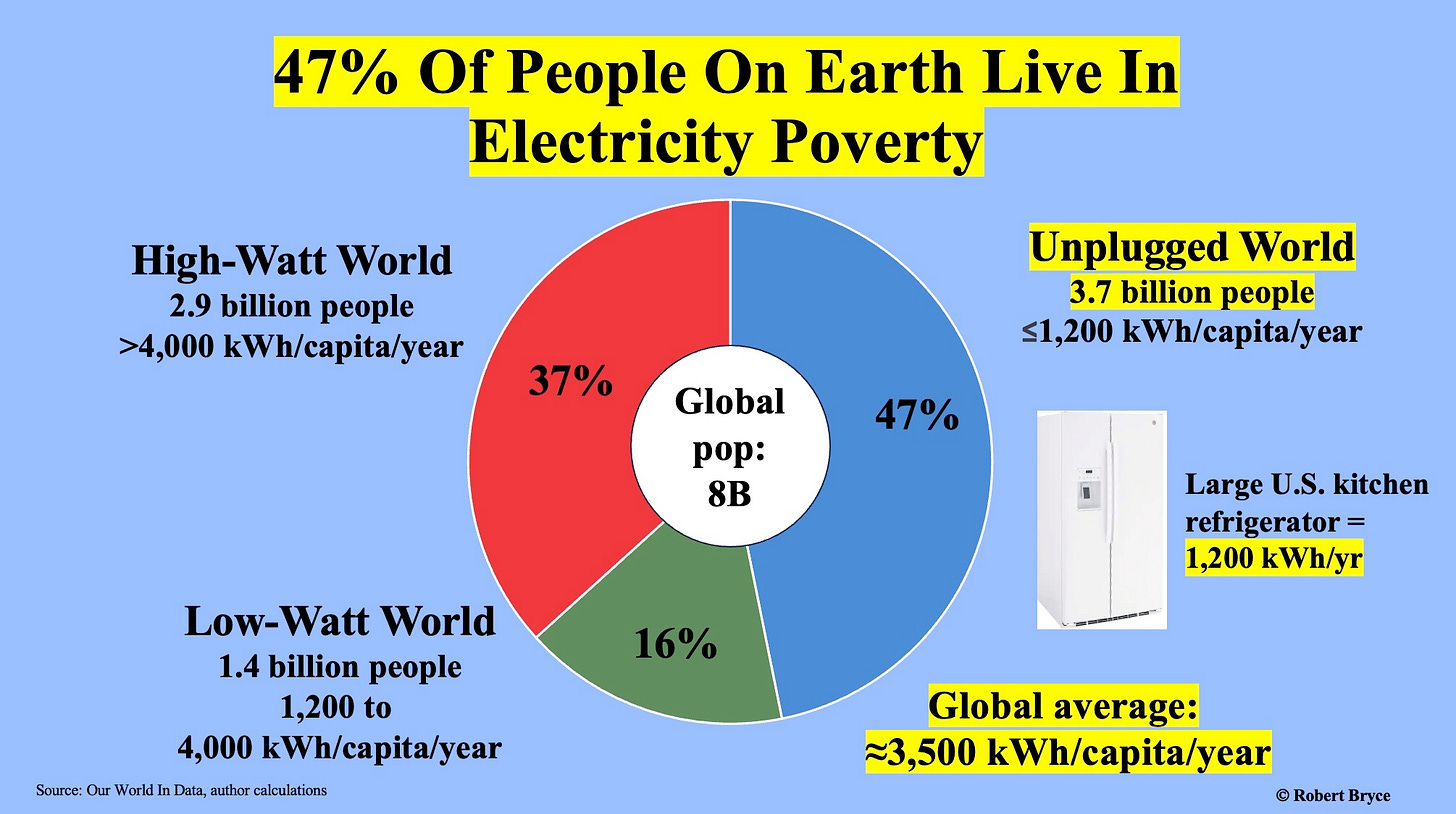

I then showed the students this slide to emphasize that electricity poverty affects some 3.7 billion people today.

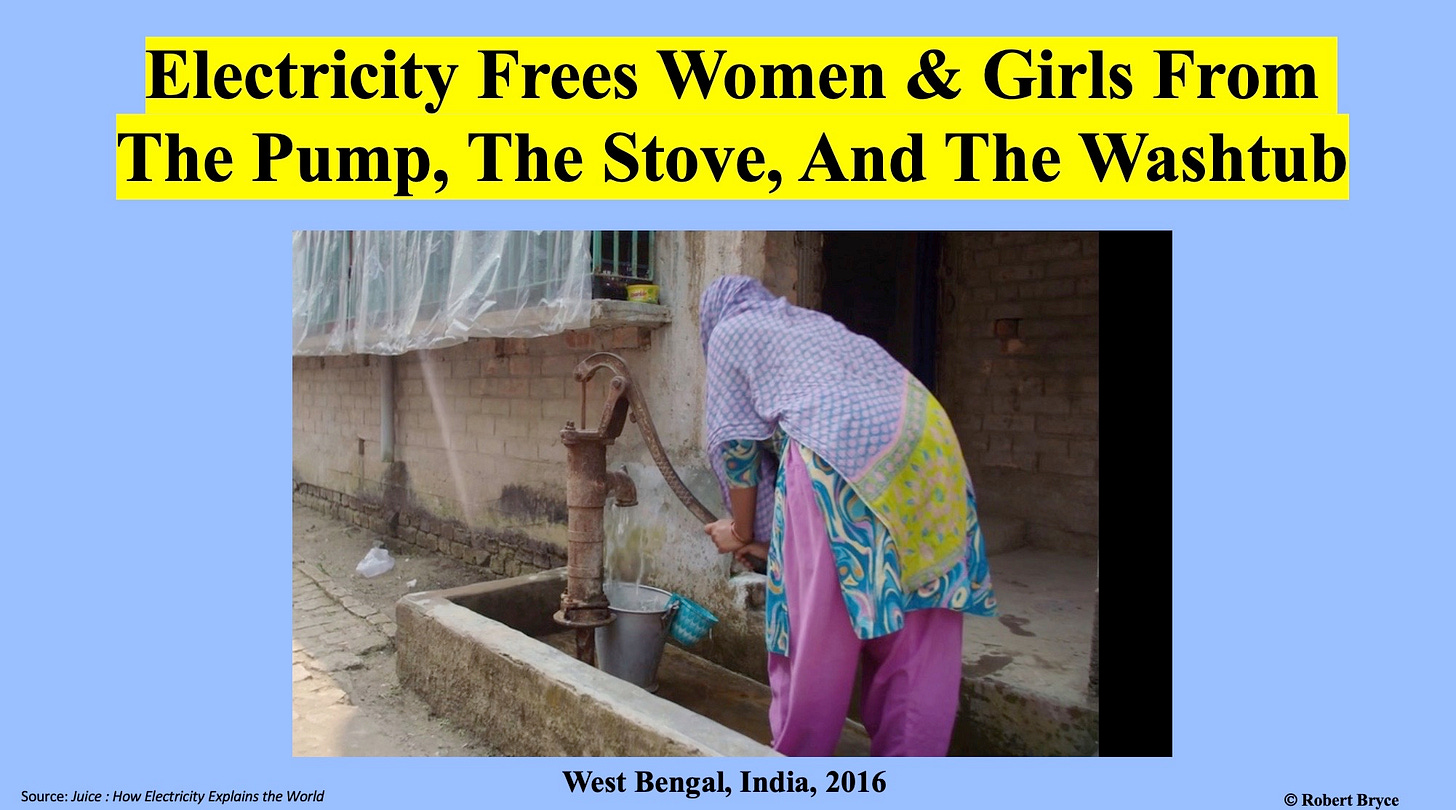

My colleague Tyson Culver shot the image of this woman pumping water by hand in Majlishpukur, the same village where I talked to Rehena Jamadar. My interview with Rehena and this image are featured in our first documentary, Juice: How Electricity Explains The World. You can watch it for free on YouTube by clicking here.

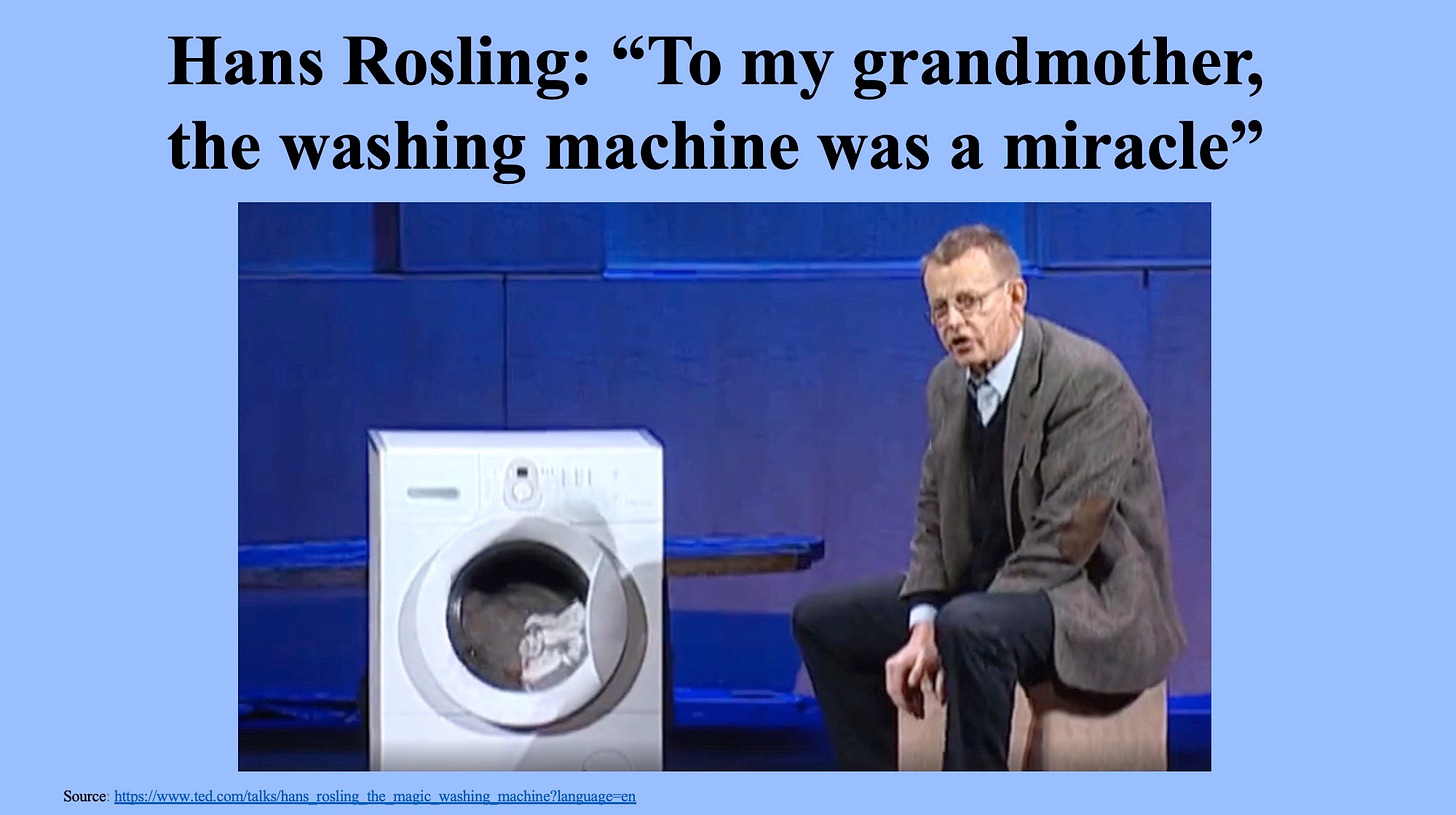

A few years ago, the late demographer Hans Rosling estimated that some five billion people are wearing clothes that have been washed by hand. That means that about 2.5 billion women and girls are doing that washing.

On Saturday, I gave the students a homework assignment. I told them they had to go home and watch Rosling’s fantastic 2010 TED talk.

I then focused on indoor air pollution and the problem of low-quality cooking fuels.

I’ve looked at these numbers many times and still find them shocking. Further, as I explain in nearly every lecture I give, these aren’t my numbers, they are the numbers. In this case, they come from the World Health Organization.

Again, the numbers are shocking. I explained to the students that most of those 3.2 million deaths per year could be prevented if developing countries had enough propane and butane stoves. Clean-burning LPG could replace the wood, straw, dung, and charcoal that is now being used. That, in turn, would ease the indoor air pollution problem and save untold numbers of women and girls from contracting respiratory ailments and, in many cases, from premature death.

Despite rampant energy poverty around the world, it is clear, as I wrote in May, that “Environmentalism In America Is Dead.” It has been replaced by climatism and renewable energy fetishism.

The groups pushing this anti-energy messaging are spending staggering sums of money to demonize hydrocarbons and push claims that we must only use alt-energy like wind and solar.

I then cited Rob Henderson’s powerful work. His memoir, Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social Class, was published in February and has been a smashing success. Henderson writes here on Substack. In a sharp piece called “The Grand Canyon-Sized Chasm Between Elites and Ordinary Americans,” he laid out his thesis on “luxury beliefs.”

During my presentation at Benedictine College, I reminded the students that the Catholic Church “proclaims that human life is sacred and that the dignity of the human person is the foundation of a moral vision for society. This belief is the foundation of all the principles of our social teaching.” The US Conference of Catholic Bishops continues, saying, “We believe that every person is precious, that people are more important than things, and that the measure of every institution is whether it threatens or enhances the life and dignity of the human person."

Regardless of whether or not you are Catholic, it is beyond dispute that energy enhances the life and dignity of the human person. If we are to be humanists, we have to be energy realists. That led to my final two slides.

As always, I ended my presentations by mentioning the decarbonization strategy I’ve been pushing for 15 years, N2N: natural gas to nuclear.

It’s a joy and a privilege to talk to students. I told them they don’t have to trust me or what I’m telling them. I encouraged them to do their own research. When one of the students asked about climate change, I repeated what I’ve said many times: Yes, climate change is a concern. It is not our only concern. We have to balance whatever efforts we make on decarbonization with the other needs in society, including, in particular, ensuring that we keep our energy and power systems affordable, reliable, and resilient. That's the humanist view.

I hope my presentations convinced some of the students to adopt a pro-energy, pro-human outlook.

Before you go, please do me a favor:

Click on that ♡ button, share, and subscribe. Thanks.

I would have asked some of the girls in the audience to come up front and wash clothes for 10 minutes while you gave the lecture in the dark. It would have required you to write the information on a chalk board (since your power point won't work in places without electricity). Having been to India, I get your point. I am not sure kids get it. The experiential learning is best. Maybe have a whole day where kids walk to school, have food cooked over an open fire, no electricity and cell phones and tablets and walk home. Then bring them to the ER and let them see all the lifesaving measures made possible by crude oil. And their car that needs fuels for oil and break lines and electrical wires to run the car radio, don't forget that!

A drop of reason in a desert of lunacy