Electrifying Democracy

Rural electrification is America’s greatest infrastructure achievement

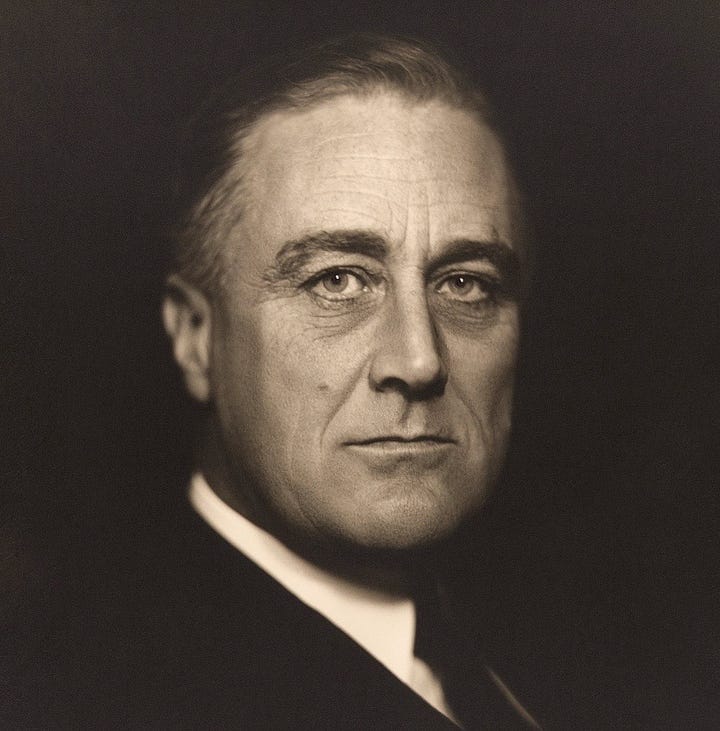

By the time Franklin Roosevelt took office in 1933, the federal government was already playing a significant role in the electricity sector. In 1918, the government began construction of the Wilson Dam at Muscle Shoals, Alabama. The project, which dammed the Tennessee River, was designed, in part, to provide electricity to a nitrate plant which could help supply the US military with explosives. In 1931, federal workers began construction of the Hoover Dam, on the border of Nevada and Arizona. That project would become a critical part of water management and electrification in western states. In 1933, the federal government created the Tennessee Valley Authority which had broad authority to provide flood control, electricity production, and economic development to the people living in the southeastern US, a region that was plagued by poverty and disease.

By 1935, Roosevelt was ready for more aggressive action to stimulate the still-languishing economy, including a full-scale push for federal intervention in the electricity sector. In his State of the Union address, he made it clear that he planned to bust the public utility holding companies, saying it was time for the “restoration of sound conditions in the public utilities field through abolition of the evil features of holding companies.” To beat the big utilities, Roosevelt needed powerful allies on Capitol Hill who would get the legislation passed. He found three, all of whom were as committed as he was. Two of the three — Sam Rayburn from Texas and Burton Wheeler from Montana — were Democrats. The third, George Norris, was a Nebraska Republican. Their names are on the two bills — the Rayburn-Wheeler Act of 1935 and the Norris-Rayburn Act of 1936 — that busted the monopolists and assured lighting and power for tens of millions of rural Americans.

I’m recounting this history today, July 4, because rural electrification is the single most important infrastructure achievement in American history. Yes, the United States has built canals, dams, roads, bridges, and the interstate highway system. But rural electrification fundamentally changed the face and history of America, and it’s essential to understand that it occurred within living memory.

Ronald and Violet Cauthon, two dear friends who grew up in rural Oklahoma in the 1930s and 1940s, vividly remember the hardships of those pre-electricity days. In an email, Ron recalled “My Mother washed clothes for the family of eight by hand. Water was heated in a large wash tub, scrubbed on a washboard, then rinsed in a separate tub of clear water.” He continued, saying that lighting in their home near the small town of Vinita, “was provided by glass lamps fueled by kerosene or as we called it ‘coal oil.’ We purchased the oil from a 55-gallon drum at the small grocery store owned/operated by three of Dad’s cousins.” He said when his family’s home got electricity in the 1940s, it was “an exciting and almost unbelievable event.”

More on Ron and Violet in a moment.

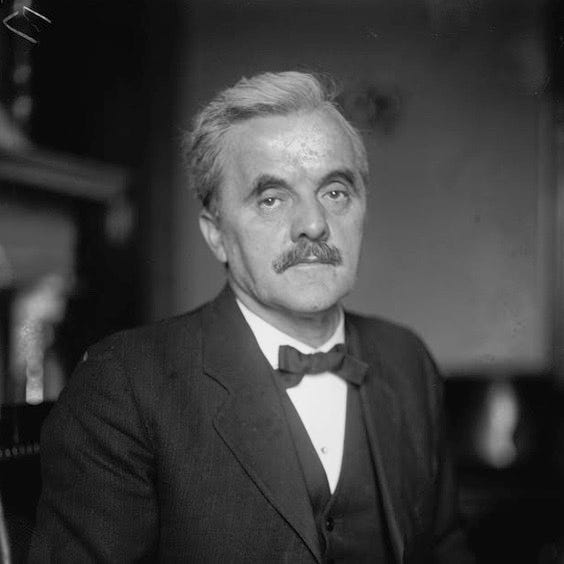

Rayburn and Wheeler were both born in 1882, the same year Edison started producing commercial electricity at the Pearl Street station in Lower Manhattan. Rayburn knew from personal experience the drudgery that came with living in the dark. He’d grown up working on his family’s 40-acre cotton farm near the town of Bonham, a few miles south of the Red River. Rayburn began his stint in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1913 at the age of 30.

Without electricity, Rayburn said, rural farmers and ranchers were merely “unwilling servants of the washtub and water pump.” He also said, “I want my people out of the mud and I want my people out of the dark.” (Rayburn would go on to be the longest-serving Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives.)

Wheeler was — as he later titled his autobiography — a Yankee from the West. Although he represented Montana in the US Senate, he was born and raised in Massachusetts and attended law school at the University of Michigan. In 1905, he settled in Butte, Montana. In 1922, his constituents elected him to the US Senate. By the mid-1930s, Wheeler had been involved in many tough fights on Capitol Hill. But the clash over the holding companies was “the biggest, bitterest, and most extravagant” of his career.

While Rayburn and Wheeler were essential players in the fight for rural electrification, they might not have succeeded without Norris. Born in 1861, Norris was instrumental in creating the structure of Nebraska’s state government, which is the only one in the country with a unicameral legislature. A flinty lawyer who abstained from drinking alcohol his entire life, Norris was an ardent believer in the power of government to help people. He was also deeply suspicious of big business and an enemy of Henry Ford.

By 1935, Rayburn, Wheeler, and Norris were all formidable players on Capitol Hill. That year, they introduced the Rayburn-Wheeler Act — better known as the Public Utility Holding Company Act — the key provision of which was known as the “death sentence.” It required all of the holding companies that “were not parts of geographically or economically integrated systems to dissolve or reorganize themselves” by 1938.

The holding companies reacted to the prospect of Rayburn-Wheeler with fury. They spent some $1.5 million ($33 million in 2023 dollars) trying to defeat the legislation, hired 660 lobbyists to push their case with members of Congress, and convinced supporters to send 250,000 telegrams and 5 million letters to members of the House and Senate. As the fight heated up, Will Rogers weighed in on the debate. In the mid-1930s, Rogers, a Cherokee who was born in Oologah, Oklahoma, was among the most famous people in America. (Rogers is my fifth cousin.) He was an actor, humorist, and trick roper, and his syndicated columns were carried in newspapers that were read by 40 million Americans. Rogers wisecracked that the holding company is “something where you hand an accomplice the goods while the policeman searches you.”

In 1935, despite the holding companies’ campaign to derail the legislation, the Public Utility Holding Company Act became law. In 1936, Congress passed the Norris-Rayburn Act, better known as the Rural Electrification Act. It established the Rural Electrification Administration as an independent federal agency and charged it with providing loans for the construction and operation of generating plants, as well as distribution and transmission lines, for the provision of electricity “to persons in rural areas.”

In 1945, in his memoir, Fighting Liberal, Norris wrote that federal backing for rural electrification “constitutes one of the largest organizations of a governmental nature ever undertaken in the United States. Its benefits to the rural population have been of mammoth proportions and will grow constantly as electricity is carried to thousands more farms in all areas of the country.”

The wiring of rural America after the New Deal not only helped set the stage for America’s emergence as an economic superpower, it also helped assure that women and girls were not stuck on rural farms and ranches doing menial labor. The desire to help farm women was one of the reasons Norris pushed so hard for rural electrification. “From boyhood, I had seen first-hand the grim drudgery and grind which had been the common lot of eight generations of American farm women.”

In the early 1930s, before Roosevelt, Rayburn, Wheeler, and Norris took on the holding companies, nine out of 10 US farms lacked electricity. By 1950, those figures were reversed, and nine out of ten farms in America were connected to the grid.

Cheap electricity from rural coops and federally funded hydropower projects fueled a rapid increase in living standards. Between 1940 and 1970, electricity production in the US grew nine-fold to more than 1,600 terawatt-hours. Over that same three-decade period, US gross national product increased nearly ten-fold, going from $100 billion to $977 billion.

For Violet Cauthon, the impact of electrification was real. “For years, my grandmother (born in 1885) used a big black pot filled with water and hung it over a fire for her laundry,” she explained by email. “That same black pot was used to make hominy from dried corn as well as lye soap. When mother was growing up, she and her next-oldest sister carried dirty clothes about a mile to a creek. They built a fire, filled a big pot with water and did all the laundry at the creek.”

She continued, “I remember visiting Cherokee relatives in eastern Oklahoma who were without electricity in the WWII years. They shared a nice stone springhouse built into the side of a hill with a Cherokee neighbor. That’s where butter and milk was stored on benches. The cold spring water flowed over the benches keeping food cool.” Today, Violet told me, we “take electricity for granted, of course. But I remember how rural families and ranchers were ‘over the moon’ when the REA was ordered by FDR.”

We hear a lot about the need to upgrade America’s electric grid. But the difficulty of making that happen is due, in part, to its diffused ownership. Our electric grid contains hundreds of living remnants of the New Deal, including about 850 electric coops and 2,000 publicly owned utilities. Add in a handful of federal power agencies and some 180 investor-owned utilities, and you find that the U.S. has about 3,400 electric providers. For comparison, Japan has 10 and France has seven.

We have many reasons to celebrate Independence Day in America. Yes, we face myriad challenges in our politics and our infrastructure. But our electric grid and the wealth and prosperity it delivers to urban and rural Americans remains one of the wonders of our history.

A final note for July 4: Today, we released a new episode of the Power Hungry Podcast. My guest is Peter St. Onge, an economist with the Heritage Foundation who has become a phenom on TikTok and Twitter. St. Onge predicts hard times are coming for the U.S. economy. But he is also bullish on the U.S. over the long term because “the Constitution is our superpower.” It is, he said the “North Star” for our culture.

I agree.

I invite you to listen to that episode, and all the other episodes of the Power Hungry Podcast, including the one we published last week with my friend, Lisa Linowes. And while you are on YouTube, please subscribe.

Before you go:

Please click the ♡ button.

This article is adapted from my latest book, A Question of Power: Electricity and the Wealth of Nations which recently came out in paperback. Remember, you don’t have to read it, you just have to buy it!

If you haven’t done so, please subscribe to this Substack and share it.

Happy Independence Day.

The women of the 3rd world face the same killing drudgery Robert describes in the US prior to electrification. They are the “utility workers” gathering wood and dung and water for the family. They are enslaved to these tasks. These folks need reliable 24X7 electricity. Not intermittent, weather dependent electricity which makes Westerners feel good.

Growing up in the fifties our electricity was always referred to as the REA . My Dad was so happy to finally make the dairy operation all electric. Today my electricity provider is a coop. Just got notice of rate drop starting Aug 1. no need for State Utility board to approve since it is member owned .