Fire Sale

Hydrocarbon demand is booming but Mr. Market hates oil and gas stocks.

Last month, in Sevierville, Tennessee, Buc-ee’s opened the world’s largest gas station. The new retail store has 120 fuel pumps and employs about 350 people. The interior space of the new store covers 74,000 square feet. (A football field covers about 57,600 square feet.) It also has a 250-foot-long car wash that will be one of the longest in the country.

Buc-ee’s, which is based in Texas and has about four dozen locations, doesn’t allow 18-wheel trucks at its locations. As a company spokesman explained: “We are set up for the family traveler…we don't have the space or the capacity to hold 18-wheelers in the lot.” All those family travelers who will be stopping at Buc-ee’s to get a refill on brisket, beef jerky, and 20 gallons of dino-juice show why gasoline will stay around for years to come.

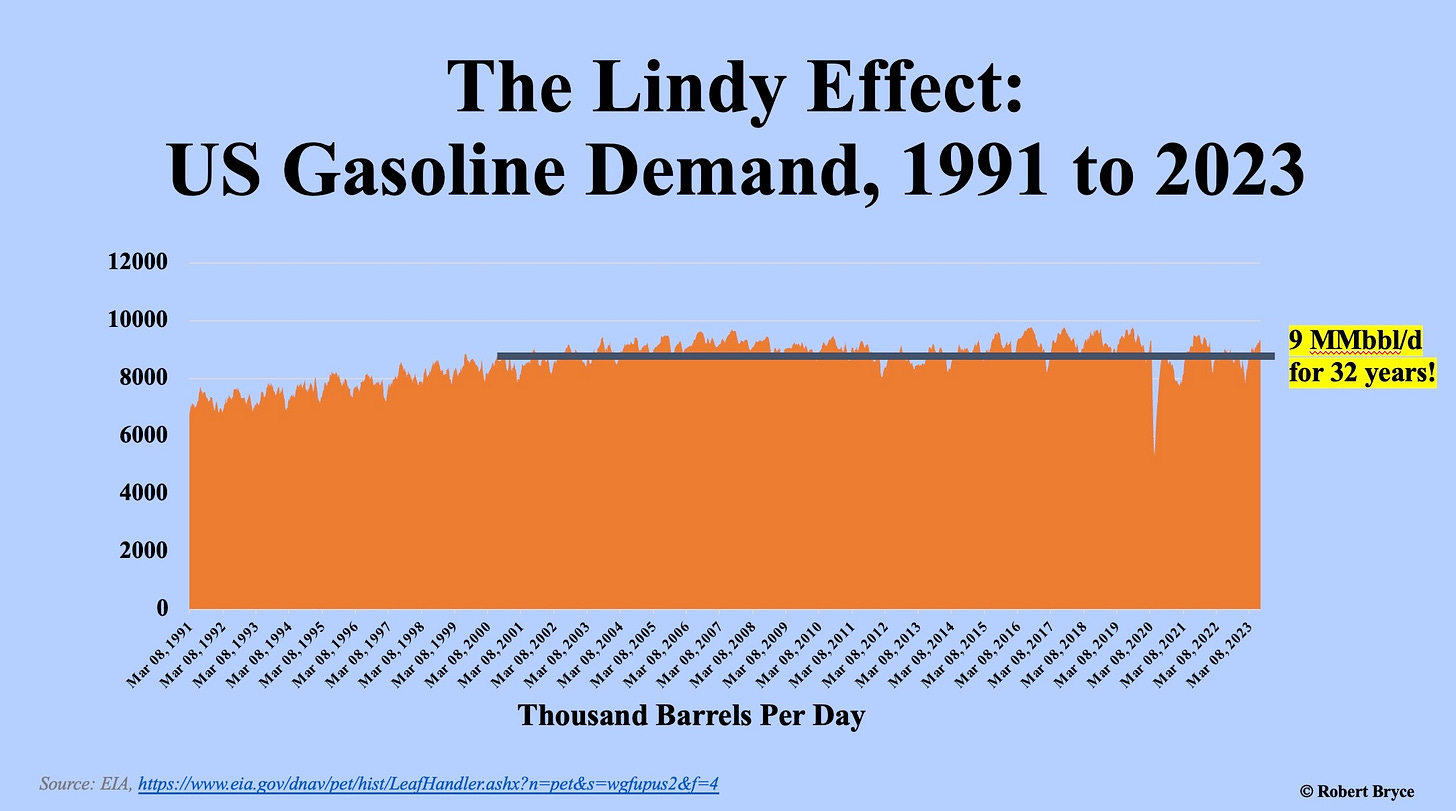

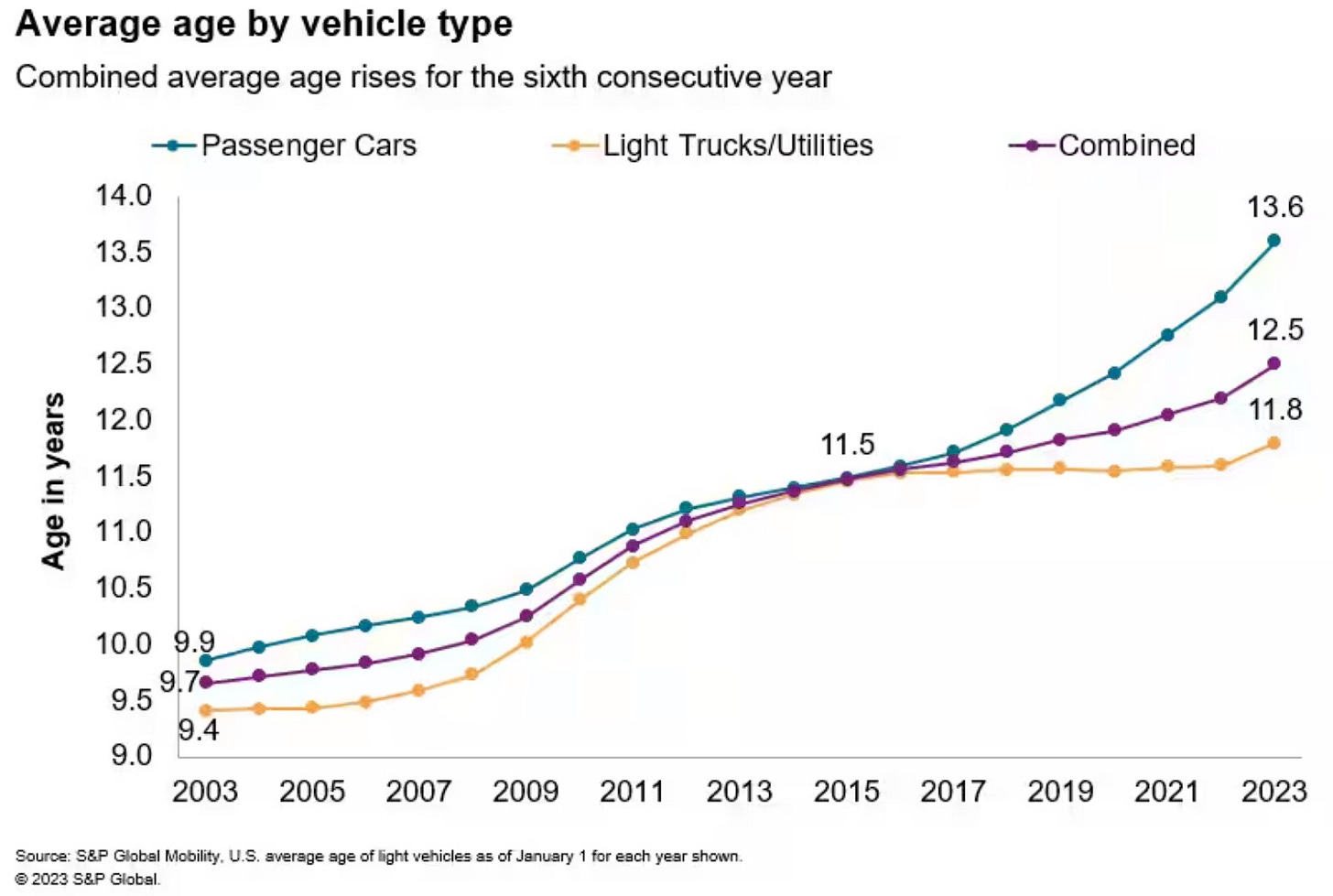

Indeed, wagering on gasoline’s staying power looks like a safe bet. As can be seen in the graphic above, U.S. gasoline demand has been at 9 million barrels per day for more than 30 years. Demand will stay strong because America has a vast fleet of cars and trucks that burn gasoline and they aren’t going away anytime soon. Yes, EV sales are growing. But new cars (EVs included) are expensive. It’s usually cheaper to maintain an older car than to buy a new one. And the longer motorists keep their cars, the longer they are likely to keep them because vehicles built by brands like Toyota, Honda, and Nissan, were designed to last for many years.

In May, S&P Global Mobility reported: “With more than 284 million vehicles in operation on US roads, the average age of cars and light trucks in the US has risen again this year to a new record of 12.5 years,” adding this was “the sixth straight year of increase in the average vehicle age of the US fleet.” S&P continued, noting “the volumes of vehicles ages 6-14 will grow by another 10 million units by 2028, adding to an already favorable volume of vehicles in the aftermarket target range.” (My driveway provides proof of the aging fleet. Our youngest vehicle is a 2012 Acura. The oldest: a 2005 4Runner. We’ll be keeping that vehicle for another decade. Why? We just put a new engine in it.)

The continued demand for gasoline reflects the Lindy Effect. Author Nassim Nicholas Taleb explained the Lindy Effect in his 2012 book, Antifragile: Things That Gain From Disorder. He wrote, “If a book has been in print for 40 years, I can expect it to be in print for another 40 years.” Put another way, the older something is, the more likely it is to be around in the future. Given the growing age of the U.S. auto fleet, as well as the 32-year history of gasoline demand, it’s logical to assume the Lindy Effect will apply to gasoline.

Jet fuel demand is also booming. A report published this month by India-based Fortune Business Insights projected the global aviation fuel market will grow from $352 million in 2022 to about $656 million by 2029. Like jet fuel, diesel fuel remains an irreplaceable transportation fuel. That’s particularly true in developing countries. In May, diesel fuel demand in India hit a new record of 2 million barrels per day.

A few days ago, the International Energy Agency projected that global oil demand will climb by about 2% this year, and reach a new record of 102.1 million barrels per day. The Paris-based agency expects demand to grow by another 1.1 million barrels per day in 2024.

What about natural gas? Demand for that fuel continues to be robust, both here in the U.S. and around the world, and according to McKinsey, it will continue to grow for at least another decade. As I reported here on July 1, in The Energy Transition Isn’t, domestic use of natural gas is booming:

Domestic gas use in 2022 jumped by a whopping 5.4% and hit a record 85.3 billion cubic feet per day. In March, the Energy Information Administration reported that gas consumption set monthly records in 9 of 12 months in 2022. Not only did annual use hit a new record, but the U.S. also set a new record for daily high demand. On December 23, U.S. gas use hit 141 billion cubic feet. The previous record was 137 billion cubic feet per day.

Given all of these facts, why don’t investors like the companies that produce oil and natural gas? And why am I writing about the stock market?

Before going further, let me be clear: I don’t own any of the stocks that are mentioned here. I am not a financial analyst and I am not offering investment advice. The vast majority of my investments are in ETFs. As I have mentioned many times on the Power Hungry Podcast, my biggest holding is the Schwab Dividend ETF.

I’m writing about the stock market because the discounts on oil and gas stocks reflect a belief that oil and gas are going away. But there’s scant evidence to support that claim. As I have said many times, if oil didn’t exist, we’d have to invent it. It’s a miracle substance. Commerce requires transportation. Transportation requires oil. If there’s no oil, there’s no commerce. Put short, as Art Berman has said, oil is the economy.

Given these facts, why are oil and gas stocks selling at such a discount to the broader market? I’ve been discussing this with my brother, Wally Bryce, for months. Wally is an above-average brother. He’s also a CPA, a savvy number cruncher, a longtime insurance executive, and an avid stock market observer. His analysis: “Mr. Market is saying this stuff is going away.” (Mr. Market is an allegory invented by Benjamin Graham to describe the workings of the stock market and as Wikipedia explains, “the danger of following groupthink.”)

The discounts are also occurring because some institutional investors are divesting from hydrocarbons. To cite just one example, in 2021, Harvard University announced it would quit investing in fossil fuels. As Wally explained it, “A lot of investors are saying ‘I won’t buy these stocks at any price.’ They are refusing to buy them. A lot of the big endowments, pensions, and foundations are saying ‘we won’t touch it.’ There are fewer buyers in the market. And the buyers aren’t buying even though by most financial metrics, these stocks are incredible bargains.”

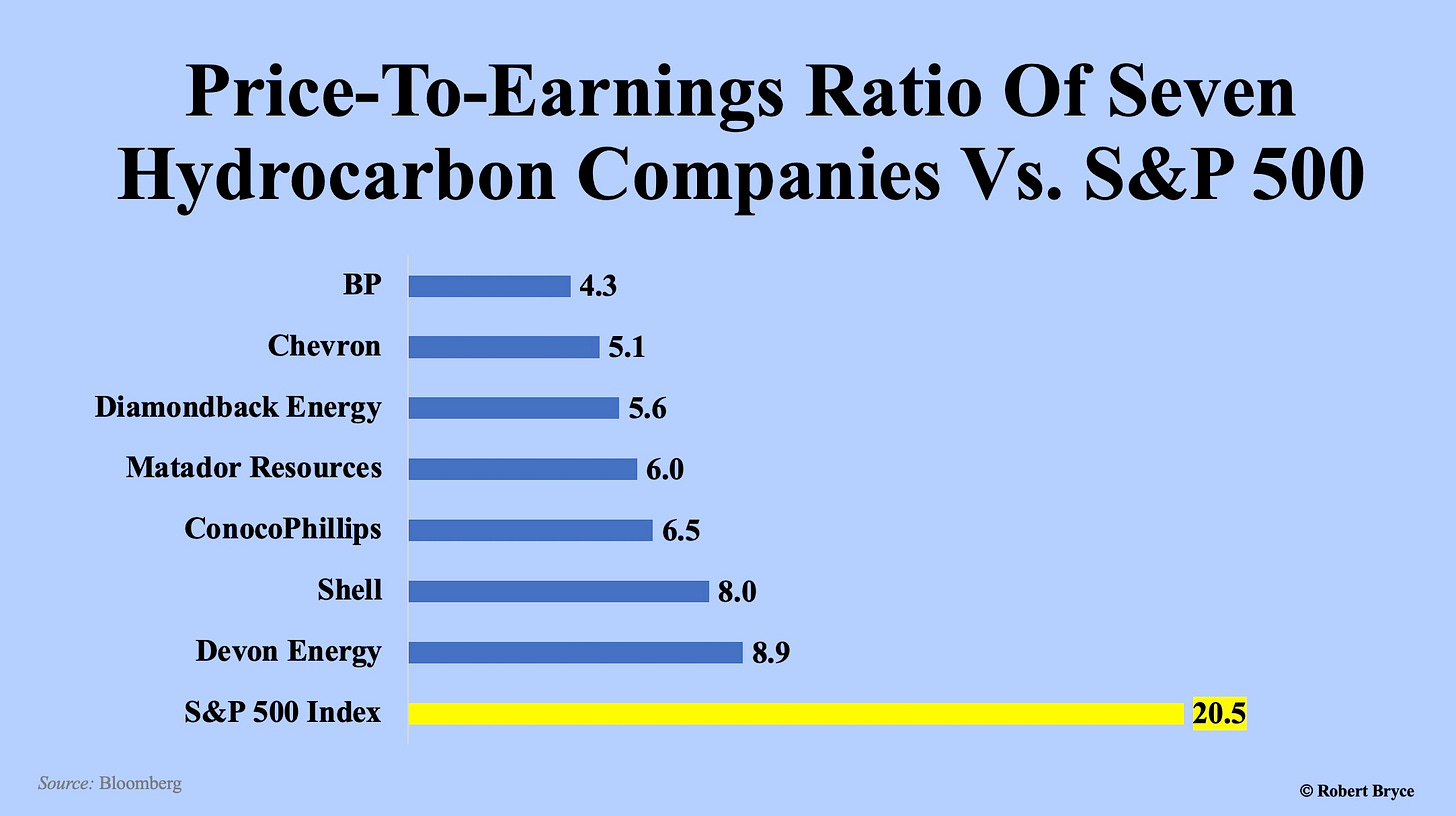

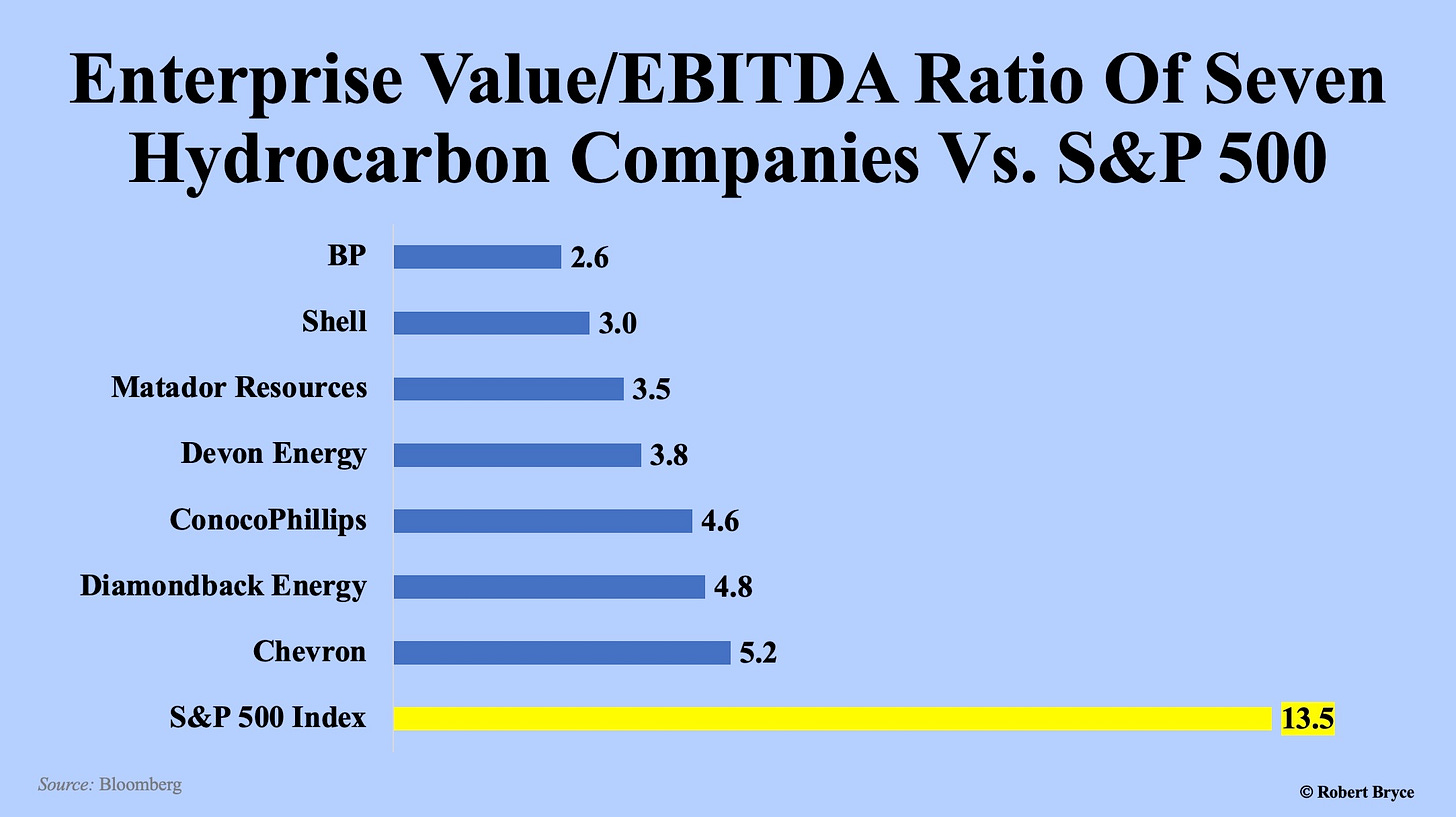

To get a snapshot of the discounts, I asked my favorite investment analyst to do a quick analysis of the companies that are trading with the biggest discounts relative to the broader stock market. My analyst (who’s based in Fort Worth and asked that I not use his name) used his Bloomberg terminal to screen oil and gas companies and find the ones selling at the steepest discounts to the broader market. He included supermajors and independents. He did two screens, one for the price-to-earnings ratio (P/E), and another for enterprise value divided by earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization, (EV/EBITDA).

The P/E is the ratio of a company's current stock price to its earnings per share. It is often used for valuing companies and to find out whether they are overvalued or undervalued. In theory, the lower the P/E, the more undervalued the company. EV/EBITDA is another widely used valuation metric. A company’s enterprise value is the sum of its market capitalization, plus its total debt, minus its cash on hand. EBITDA is a measure of a business's ability to generate cash. In short, EV/EBITDA shows the likely payback period of an investment in a given company. If a company has an EV/EBITDA of 5, it will take about 5 years for you to recover the cost of acquiring it through its EBITDA.

My analyst’s screens, which used numbers from the last 12 months, turned up seven companies. As can be seen in the graphic above, British supermajor BP is selling at a huge discount to the S&P 500. BP has a P/E of 4.3, which is a major discount to the S&P Index average of 20.5. Oklahoma City-based Devon Energy has a P/E of 8.9, which is less than half the average of the S&P 500. Need another comparison? EV maker Tesla Inc. has a P/E of 84!

Now to EV/EBITDA. The lower the EV/EBITDA figure, the more undervalued the company. Investopedia says a company with “an EV/EBITDA value below 10 is seen as healthy.” As can be seen in the graphic below, the supermajors are all selling at big discounts to the S&P 500. So are the independents, including Devon and Diamondback.

Is this the time to buy energy stocks? Maybe. Oil and gas companies are returning big chunks of their profits to shareholders and many analysts see them as value stocks. The companies are aggressively buying back their stock and boosting dividends. But they are also being challenged by fears of an economic slowdown. Furthermore, the industry faces significant political risk from the Biden Administration. I don’t say that as a partisan. I’m not a Republican or a Democrat. I am disgusted.

But this fact is simply true: the Biden Administration is the most anti-hydrocarbon administration in American history. I could cite numerous examples to prove that point. I’ll give you just two: On his first day in office, Biden canceled the Keystone XL Pipeline. In May, his EPA issued a proposed rule that could hamstring nearly all of the coal-fired, and gas-fired power plants in the country. As I noted in my piece, EPA v. The Grid, the agency:

announced a proposed rule that could force the closure of every coal-fired power plant in America as well as most of the natural gas plants if they cannot cut their emissions by 90%. Here’s how Politico reported on it: The new rule will require, “most fossil fuel power plants to slash their greenhouse gas pollution 90% between 2035 and 2040 — or shut down.”

While the political risk from Biden and the ESG crowd is real, the bigger problem may be the industry’s remarkable ability to find and produce hydrocarbons. The oil and gas sector has a century-long history of boom and bust in which it has repeatedly been victimized by its success. While it’s true that the global supply of hydrocarbons is finite, it’s also a truism that the more oil and gas we find, the more oil and gas we find. And the more oil and gas that gets produced, the more efficient drillers get at pulling it out of the ground. The decades-long problem for the oil industry hasn’t been too little oil, it’s been too much. That fact gave us prorationing under the Texas Railroad Commission for 40 years, until 1973, when that job was seized by OPEC. (Which, by the way, copied the TRC’s prorationing model.)

Ten years ago, the average new-well oil production per drilling rig in the Permian Basin was about 200 barrels per day. Today, according to the Energy Information Administration, the average new-well production per rig in the Permian is about 1,000 barrels per day. That increase in efficiency means the industry needs fewer drilling rigs and fewer roughnecks, which means lower costs. That’s great for consumers, but it can be hell on investors. In short, there are many wildcards at play including the global economy (and therefore energy demand), the future of the ESG movement, and maybe most important, the sector’s ability to cut costs and boost output.

A final note: Buc-ee’s recently broke ground on a new location outside of Luling, Texas. When it opens later this year, it will seize the crown of the world’s largest gas station from the Sevierville location. The Luling store will have 75,000 square feet of shopping space.

Before you go:

Please click that ♡ button.

I’ve had lots of great guests on the Power Hungry Podcast lately, including Chris Keefer, Arjun Murti, Jusper Machogu, and Peter St. Onge. I also had a challenging chat with climate activist Bill McKibben. Check them out here.

Speaking of podcasts, I was on Jordan Peterson’s podcast about 10 days ago. I had a great time and am getting good feedback. I hope to go back on Jordan’s podcast when our new documentary comes out this fall. (More on that later.)

Thanks.

Great article, Robert. Hydrocarbons continue to be an amazing energy carrier. This is illustrated by asking the question, "How far can a Prius go with a full tank of gas?" Google just informed me that

"With a full tank of gasoline and a full charge, the 2021 Toyota Prius Prime achieves a total driving range of up to 640 miles combined. The plug-in hybrid car also has an electric-only range of 25 miles in EV Mode." Jan 26, 2021 If air pollution reduction was the goal instead of virtue signaling, governments would be pushing hybrids in addition to the currently-fashionable EV promotions.

Goehring & Rozencwajg (G&R) are contrarian analysts. Their June 15, 2023 article, "Hubbert's Peak is Finally Here" https://blog.gorozen.com/blog/hubberts-peak-is-finally-here is relevant thought-provoking reading after reading Robert's "Fire Sale" analysis. I suggest downloading their Q1 2023 newsletter via the link part way down the page. (They request your email address etc.) G&R discuss a dataset back to 1900 examining periods when commodities are undervalued in the second essay. Note also their analysis of natural gas price trends later on in their newsletter. G&R were one of the first analysts to predict significant increases in the price per MW for wind and solar. They understood that the cost of energy to produce those generating means was often overlooked. Declining energy costs were one reason why solar and wind costs began to decrease circa 2010. Since about 2020, solar and wind costs have been rising, even with China's use of Uyghur slave labor to construct solar panels. (As a consequence of its high energy density, nuclear fission power is much more insulated from these challenges.)