No U

The nuclear renaissance needs dozens of tons of nuclear fuel. We don’t have it.

Ever since the Arab Oil Embargo of 1973, American energy policy has largely orbited around the hackneyed idea of “energy independence.”

I put that phrase in quotes because the concept has never had a clear definition or concrete goal. The idea of energy independence has been used to justify a myriad of policies including oil shale (not shale oil), corn ethanol, cellulosic ethanol, and many others. As I explained in my third book, Gusher of Lies: The Dangerous Delusions of Energy Independence, the phrase provides a “prized bit of meaningful-sounding rhetoric that can be tossed out by candidates and political operatives eager to appeal to the broadest cross section of voters...With energy independence, America can finally dictate terms to those rascally Arab sheiks from troublesome countries. Energy independence will mean a thriving economy, a positive balance of trade, and a stronger, better America.”

I went on to explain that the concept gained traction after the September 11 attacks and that many Americans got “hypnotized by the conflation of two issues: oil and terrorism” and the claim that buying oil from the Persian Gulf means that “petrodollars go straight into the pockets of terrorists like Mohammad Atta and the 18 other hijackers who committed mass murder on September 11.”

But here’s the rub: over the past 50 years (it’ll be exactly 50 years in October) the dubious concept of energy independence has only been applied to oil. No other energy commodities were given the same weight or consideration. That blindness to our reliance on foreign supply chains for critical energy commodities is about to bite back in a big way.

A looming shortage of enriched uranium and HALEU (short for high assay low enriched uranium), could derail the nuclear renaissance before it gets started. And that shortage will be particularly problematic for the United States, which operates the world’s biggest fleet of reactors and accounts for about 30% of global nuclear electricity generation.

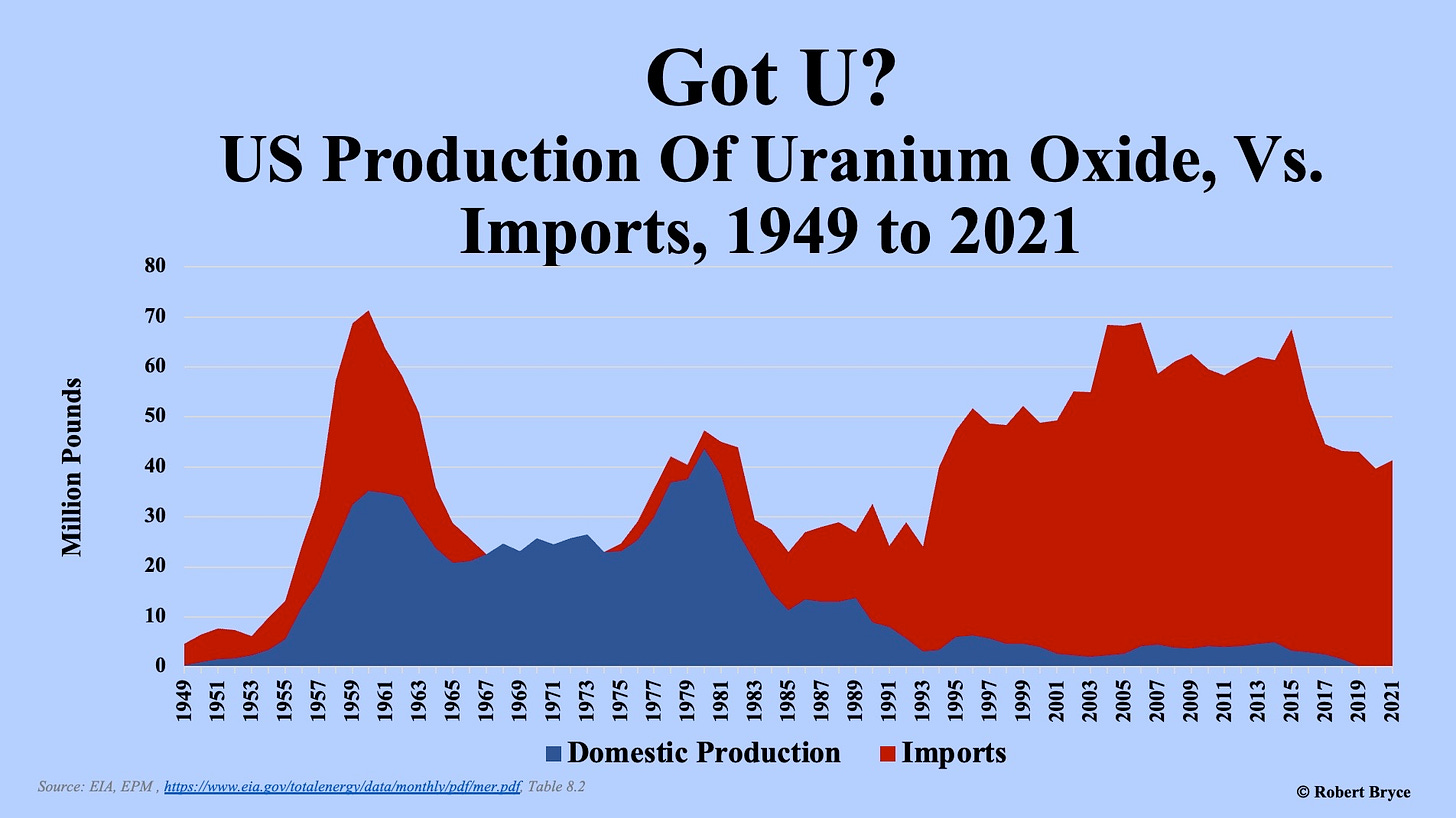

As can be seen in the graphic below, four decades ago, the U.S. nuclear sector was largely self-sufficient in uranium and nuclear fuel supplies. In 1980, the U.S. produced a record 43 million pounds of uranium oxide. Today, it isn’t producing any uranium oxide. Over the past four decades or so, the U.S. went from being the world’s biggest exporter of nuclear fuel to its biggest importer. And much of that fuel (about 14%) is coming from Russia, the world’s biggest enricher of uranium. About 46% of the world’s enrichment capacity is controlled by Russia.

The U.S. wants to get off of Russian suppliers and a bill introduced in the Senate in March, authored by Sen. John Barrasso (R-WY) and three other Republicans, aims to prohibit imports of Russian nuclear fuel. But there are no credible scenarios that will fix the nuclear-fuel supply problem in short order. Reducing our reliance on foreign uranium supplies will likely take a decade or more if – and that’s an enormous if – Congress acts quickly to address the problem.

Before going further, let me be clear, there’s plenty of good news coming from the nuclear energy sector. Consider these recent developments:

In January, NuScale Power — which went public a year ago and now trades on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker SMR — won approval for its SMR design from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

On May 11, X-energy and Dow announced plans to build four of X-energy’s high-temperature, 80-megawatt gas-cooled reactors at the chemical company’s plant in Seadrift, Texas. The companies said they will submit a construction permit application to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and that they expect construction “to begin in 2026 and to be completed by the end of the decade.” (X-energy plans to go public sometime this year.)

On May 29, the Unit 3 reactor at Plant Vogtle in Georgia reached 100% of its designed power output of 1,100 megawatts, making it the first new reactor to come online in the U.S. since 2016. Further, Georgia Power expects fueling of the Unit 4 reactor to begin over the next few weeks. The generator should begin producing juice later this year.

There’s also plenty of positive news coming out of Europe. Last month, in Paris, 16 European countries met in what’s being called a new “nuclear alliance” that aims to reduce their reliance on Russian nuclear fuel. The group includes Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, France, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden, and the U.K. The group, according to one French official, aims to “relaunch” the nuclear industry in Europe. That launch is already underway. Romania, Poland, and Estonia have all announced plans to build new reactors and Britain gave approval for construction of the 3,200-megawatt Sizewell C plant last year and the government is issuing the needed permits.

But those European countries are going to be competing with the U.S. for new supplies of uranium, enriched uranium, and nuclear fuel assemblies. And they will be doing so in a business that’s dominated by a handful of countries: Kazakhstan, Canada, Australia, and Russia. And of those, the U.S. may only be able to count on Canada and Australia.

Kazakhstan, which mines about 43% of the world’s supply of uranium, has a deal to supply China with nuclear fuel and it delivered a second batch of that fuel earlier this month. Furthermore, last month, Kazakhstani authorities allowed a Russian firm to take control of a key Kazakh uranium mine. As reported by OilPrice.com “Once this mine is fully operational, Kazatomprom’s control of the uranium industry in Kazakhstan will be reduced from its current 50% dominance and will ensure that Moscow can acquire at least some of the supplies it needs. Currently, Russia uses more than twice as many tons of uranium as its domestic mines produce, 5,500 tons against 2,500 for last year.”

In other words, Russia is facing a uranium supply pinch, too. And it’s now competing with China for Kazakh uranium. Per OilPrice: “Kazakhstan may not be able to increase exports to one country without reducing them to another.”

Thus while there’s no shortage of interest, positive media coverage, and capital, the nuclear sector is facing an impending shortage of the fuels needed to run both the existing reactor fleet and the fleet of future reactors, including SMRs.

The best reporting on this topic has been done by Matt Wald, who has written two excellent articles about the fuel-supply issue for the American Nuclear Society. See here and here. On April 14, he wrote, “The American nuclear industry adheres to a philosophy of analyzing every conceivable ‘what if,’ at least for hardware. But at the moment, with nuclear fuel, the industry is in what the engineers might call an ‘unanalyzed condition.’”

Wald came on the Power Hungry Podcast last week and told me that the lack of fuel “has certainly delayed” the nuclear renaissance because so many of the new generation of reactors need HALEU. “There’s no place to get it,” he said. “It’s not a technical problem, it’s a commercial problem and especially a problem of commercial inertia.”

The lack of HALEU has already led to at least one public announcement of a delay. In December, TerraPower, a nuclear startup that plans to build an advanced reactor in Wyoming on the site of an old coal plant, said it was delaying the expected start of its reactor for two years due to the lack of fuel. “Russia’s invasion of Ukraine caused the only commercial source of HALEU fuel to no longer be a viable part of the supply chain for TerraPower, as well as for others in our industry,” said Chris Levesque, the company’s CEO. “Given the lack of fuel availability now, and that there has been no construction started on new fuel enrichment facilities, TerraPower is anticipating a minimum of a two-year delay to being able to bring the Natrium reactor into operation.”

Two years? Given current conditions, it will more likely take four years, or even longer.

In February, Centrus Energy, the only domestic producer licensed to produce HALEU, said that “A full-scale HALEU cascade, consisting of 120 individual centrifuge machines, with a combined capacity of approximately 6,000 kilograms of HALEU per year, could be brought online within about 42 months of securing the funding to do so.” But Centrus hasn’t secured the needed funding. And six metric tons won’t be nearly enough to meet demand. The Department of Energy estimates that more than 40 metric tons of HALEU will be needed by 2030.

This week, I talked to a nuclear engineer who has spent decades in the industry and asked not to be named. “It’s a classic chicken-and-egg problem,” said the engineer. “You can’t produce the HALEU without solid orders for new reactors. But you can’t get reactor orders if you can’t be sure you’ll have fuel.”

Congress has recognized the problem. The Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee held a hearing on nuclear fuel in March. At that hearing, Joseph Dominguez, the CEO of Constellation Energy, the biggest producer of nuclear electricity in America, was blunt, saying the U.S. is “on the verge of a crisis in conversion and enrichment” of nuclear fuel. Constellation operates 23 reactors in five states with a total capacity of 21 gigawatts. On June 1, it bought NRG’s stake in the South Texas Project. (Austin Energy owns 16% of STP.)

Dominguez said “It is critical that we re-shore our capability to overcome global dominance by Russia in these areas. We do not have time to wait...Congress must authorize and fund a $3.5 billion investment as part of a public-private cost-share partnership with conversion and enrichment suppliers.”

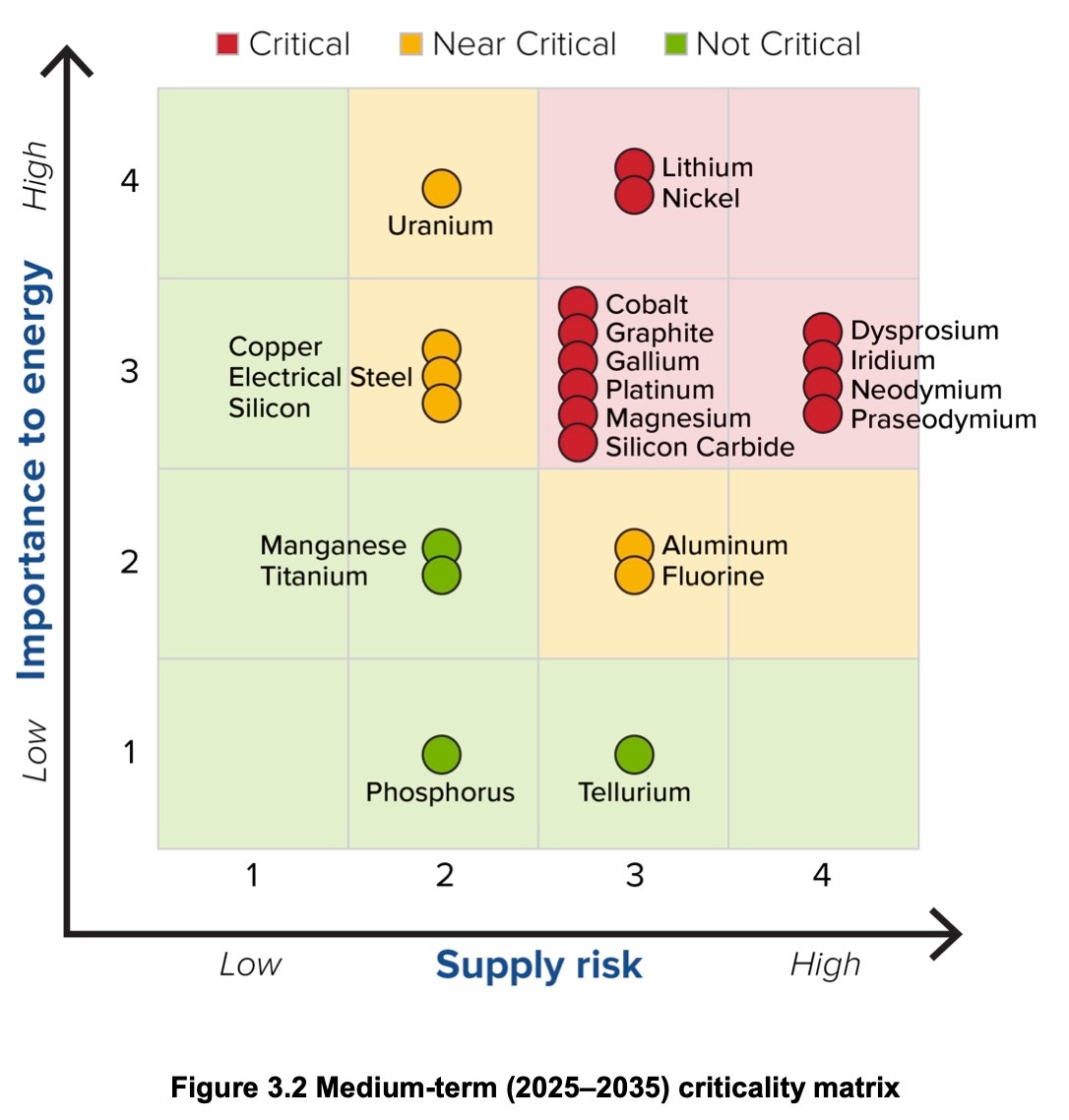

The DOE appears to be waking up. The agency released a report last month called the “Critical Materials Assessment, 2023.” It ranked uranium as a “near critical” material that is facing substantial supply risk. On Monday, the agency said it is seeking “feedback” on two requests for proposals to acquire HALEU. In a June 5 press release, it noted that last year’s Inflation Reduction Act provided $700 million for the HALEU Availability Program which was authorized under the Energy Act of 2020. But $700 million won’t be nearly enough. A full-scale enrichment project to produce HALEU will likely cost about $5 billion.

Furthermore, the U.S. doesn’t just need enrichment, it needs to be mining for uranium. But, as can be seen in the graphic below, domestic uranium mining has collapsed. Of course, lots of other countries have bigger uranium reserves than the U.S. Nevertheless, the U.S. ranks 16th in overall reserves, with about 102,000 tons. And the U.S. has large undeveloped deposits including the Coles Hill Uranium Project near Chatham, Virginia.

But even if investors wanted to mine for uranium in the U.S., the Biden administration has shown it’s unwilling to permit any new mines, of any kind, anywhere.

In January, it blocked a copper and nickel mine in Minnesota by withdrawing more than 200,000 acres near the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness from mining for 20 years. Also in January, it blocked a gold and copper mine in Alaska’s Bristol Bay. Last month, it halted plans for a copper mine in Arizona. This month, it revoked a permit for the proposed NorthMet copper-nickel mine in northeastern Minnesota. As Isaac Orr noted in a piece for the Center of the American Experiment, the move means the project “is effectively dead for the immediate future.”

The punchline here is clear: the U.S. cannot hope to decarbonize its electric sector without nuclear energy and lots of it. Yes, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, and its cumbersome and over-long approval procedures, are a major hindrance. (NuScale Power got its reactor approved in January, but the approval process took six years and cost the company more than $500 million.) But the nuclear renaissance will not happen if the U.S. is wholly dependent on imported uranium and imported nuclear fuel.

In short, Congress is going to have to formulate a comprehensive national industrial policy focused on nuclear energy. That policy will have to include domestic mining for uranium. It will also have to, as Wald said on the Power Hungry Podcast, create the nuclear equivalent of the Strategic Petroleum Reserve so that the U.S. nuclear fleet is assured of fuel security. Affordable, reliable, and resilient electricity from our reactor fleet should be seen as a national security imperative. Having a secure source of nuclear fuel for our most important energy network, the electric grid, isn’t a luxury. It’s essential.

Wald has another good idea: Congress should fund a program that creates a floor price for enriched fuel so that domestic producers can be assured that the bottom won’t fall out of the market and leave investors in enrichment facilities with worthless assets. I’d go a step further and provide a floor price for domestically mined uranium. As Wald concluded in his May 19 article for the American Nuclear Society, the events of the past few years, combined with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, have created a “new consensus: that institutions bigger than corporations — namely, governments — should be involved.”

Getting Congress to act — and act quickly — on these issues will be difficult. But it is increasingly clear that the future of nuclear energy in America must have strong, decades-long, bipartisan support from Congress and whoever is sitting in the White House. It will also require some rethinking about the meaning of energy independence.

Clarification: Much of this article focused on the need for HALEU. I neglected to note that some of the SMR designs now aiming for commercialization don’t need HALEU. Instead, they will use low-enriched uranium, or LEU. As my friend, Rod Adams notes there are about half a dozen new reactor designs that use LEU instead of HALEU. He explains those reactors “won’t put a significant new burden” on the available supplies of nuclear fuel and should be able to build first-of-a-kind reactors and early commercial units using existing supply chains.

Before you go:

Please click the ♡ button. (It’s not radioactive.) And if you haven’t done so already, please subscribe and share.

Want me to speak at your next event? Email me: robert (at) robertbryce.com

Thanks.

I dont have access to the kinds of details that you do, but I have a few generalized comments picked up from having been investing in the sector for 20 years or longer......

There is no shortage of available uranium in the earth's crust, estimates are that we have enough known ore resources to last humanity for about 10,000 years......

For several decades Russia became the number one source for enriched uranium primarily because most of what they were providing was being salvaged from nuclear weapons that were being retired.

Uranium mining in Kazakhstan is a recent phenomenon ...only the past 12 years or so.......I've got this lovely chart from Youtube not too long ago....https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K6zL9N81NzI .... the rest of the world has not declined so much as total world production has been increasing rapidly......

The USA does have good but not great known reserves. In most places in the USA, uranium mining is banned.....for example I know of three locations in Virginia which have very rich ore right at the surface but uranium recovery is completely banned in the state ....

The Cigar Lake mine, owned and operated by Cameco Corp, in northern Saskatchewan, has huge quantities of ore that is ten times more concentrated than any other mine on earth....however the mine has always been plagued with severe water intrusion problems .... and Cameco has found it is more profitable to participate in joint mining efforts in Kazakhstan, so they have a hand in that, its not just Russian as you imply.....

The process of purifying ore to pure uranium is pretty straightforward and low tech.

But the process of separating out U235 from U238 is the tricky one. The tech and the equipment and the time involved are the hard parts. People in the USA just dont want to do it, but they also dont really want Iran or Pakistan or Kazakhstan doing it, so thats where politics come in.

For the past few months, Cameco has been trading as if it were an Artificial Intelligence stock, I have never seen anything like the jumps its been taking. So at least some people are starting to wake up to the importance and the need.......

Robert, This is an outstanding article with good research! It is ironic that Admiral Rickover invented nuclear power generation for the Nautilus which was then adapted for commercial applications starting at Shippingport and the U.S. manufacturers Combustion-Engineering, Babcock & Wilcox, Westinghouse, Allis-Chalmers and a few others for the crucial Supply-Chain provided this gift to the world. Then along comes the MSM with their attacks on nuclear after Three Mile Island (no one was killed at TMI) and certain politicians sell off Uranium One to the Russians not too many years ago. Your article is informative. Wish it would make the MSM News! Thank you!