Powering The Unplugged

Here's the first section of a new paper on electrification in developing countries that I wrote for the Alliance For Responsible Citizenship

I’m pleased to announce that yesterday, the Alliance For Responsible Citizenship published my new paper on how to bring more electricity to developing countries. It’s called “Powering The Unplugged: Overcoming the Barriers to Electrification in the Developing World.” On October 30, I will be in London attending the inaugural conference of the ARC to present my paper and moderate a pair of panels on energy. (The conference is sold out.) I will also be doing podcasts from the conference.

The ARC, created by Jordan Peterson, Dan Crenshaw, Bjorn Lomborg, Philippa Stroud, Arthur Brooks, Alan McCormick, Michael Shellenberger, and several others, is “an international community with a vision for a better world where every citizen can prosper, contribute and flourish. We are inviting you to join us in developing a better narrative in response to life’s most fundamental social, economic, philosophical and cultural questions. We reject the inevitability of decline and instead are seeking solutions which draw on humanity’s highest virtues and extraordinary capacity for innovation and ingenuity.”

In April, the ARC commissioned me to write a paper on the challenge of bringing more electricity to developing countries. It’s an issue I have been writing about for many years. It’s a focal point of my first documentary, Juice: How Electricity Explains The World (which was directed by my friend and colleague, Tyson Culver.) It’s also a theme of my sixth book, A Question of Power: Electricity and the Wealth of Nations. I’m proud of the paper and am pleased to publish the first section of it here on Substack. If you want to read the entire report, it’s available here. I will be publishing additional sections over the next few days.

Now to “Powering The Unplugged”:

Introduction

Electricity is the world’s most important and fastest-growing form of energy. It is also the most difficult form of energy to supply reliably.

Many of the world’s most pressing challenges are tied directly to electricity, including carbon dioxide emissions, women’s rights, and poverty reduction. The electricity sector matters to climate change efforts because it is the single biggest source of global CO2 emissions. Electricity matters because it is one of the world’s biggest industries. Global electricity sales exceed $4.5 trillion per year.That means that the electricity sector generates more revenue per year than global automobile manufacturing, which generated about $3 trillion in 2022. Furthermore, electricity-related investment is the biggest portion of global energy spending. This year, the International Energy Agency (“IEA”) expects that global spending on the power sector, including investment in renewables, nuclear, hydrocarbons, grids, and batteries, will total $1.2 trillion. By comparison, spending on hydrocarbons—coal, oil, and natural gas—will total about $950 billion.

Electricity matters because it is the ultimate poverty killer. No matter where you look, as electricity use has increased, so has economic growth. Having electricity does not guarantee wealth. But its absence almost always means poverty. Indeed, electricity and economic growth go hand in hand. Electricity spurs economic activity, and economic growth spurs electricity use. Westerners take electricity for granted. But nearly everything we touch—almost everything we read, eat, or wear—has in one way or another been electrified.

Policymakers must have a laser-like focus on electricity because hundreds of millions of people in developing countries, including Pakistan, South Africa, and Bangladesh, are suffering from increasing numbers of blackouts and shortages. Even energy-rich countries like Iraq are experiencing regular blackouts. Amidst this backdrop, global power demand is booming. Urbanization, economic growth, population growth, electric vehicles, and soaring use of air conditioning in countries like India—where air conditioner sales are growing by nearly 8% per year—are all fuelling the need for more electricity.

How much more power generation capacity will the world need? Over the past four decades, global electricity production doubled every 20 to 25 years. If that trend continues, global generation capacity will increase from roughly 7 terawatts today to about 14 terawatts by 2050. To put that in perspective, the United States now has approximately 1.1 terawatts of generation capacity. Thus, over the next 25 years, the world’s countries will have to add generators, poles, wires, and electricity meters roughly equal to six grids the size of the existing American grid. That is an enormous challenge. Further, it will require using all of the fuels we have available.

Over the past two decades, climate activists and policymakers, particularly ones based in Europe and North America, have repeatedly claimed that the world economy can run solely on weather-dependent renewables. Investors have responded by pumping enormous amounts of capital into wind and solar projects. According to Bloomberg New Energy Finance, between 2004 and 2021, some $3.7 trillion was spent on wind and solar. Despite that staggering investment, by the end of 2021, those two forms of electricity production were only producing about 10% of global electricity (see Figure 6).

Furthermore, numerous factors are constraining the growth of wind and solar, including land-use conflicts. As shown in the Renewable Rejection Database, local communities across the United States are fighting the encroachment of large wind and solar projects. Since 2015, there have been more than 400 rejections or restrictions of wind projects and more than 170 rejections or restrictions of solar projects. Similar land-use conflicts can be seen across Europe, as well as in Israel and Australia. In addition, the lack of high-voltage transmission capacity is hampering weather-dependent renewable projects. That capacity is necessary to move electricity from rural areas with the best wind and solar resources to urban areas where electricity demand is highest.

Although wind and solar are getting enormous subsidies and have staunch political support, the hard facts show that the global electricity sector continues to rely heavily on the incumbent sources—hydrocarbons, hydropower, and nuclear—which together provided about 87% of the world’s electricity in 2021.

Given these facts, policymakers must regard the electric sector as a critical part of the economy and focus on measures that help ensure their electricity grids can supply affordable, reliable, and resilient power to their people, factories, and water treatment plants. Furthermore, they should focus on electrification first. Concerns about decarbonisation should come second. Before addressing how to bring more power to the unplugged, we must understand the importance of electricity and the enormous disparity between the electricity rich and the electricity poor.

Mind The (Power) Gap

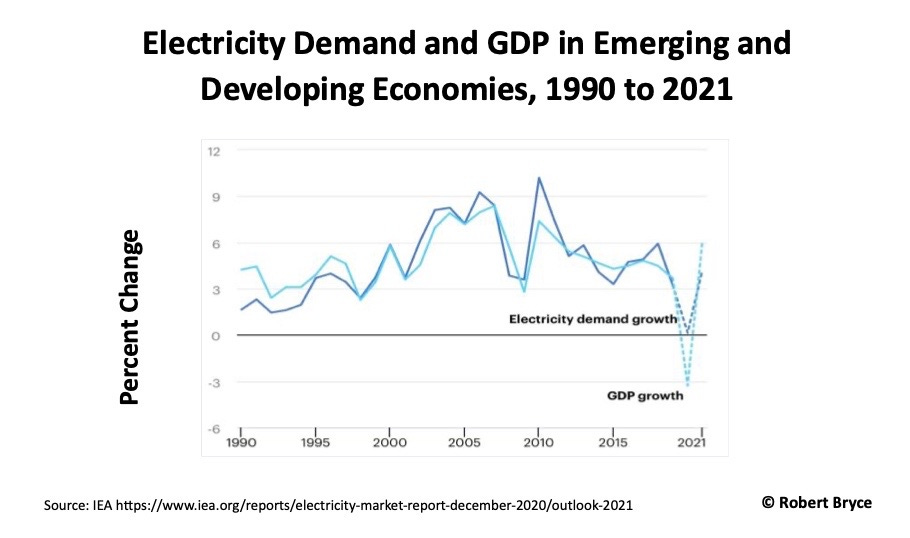

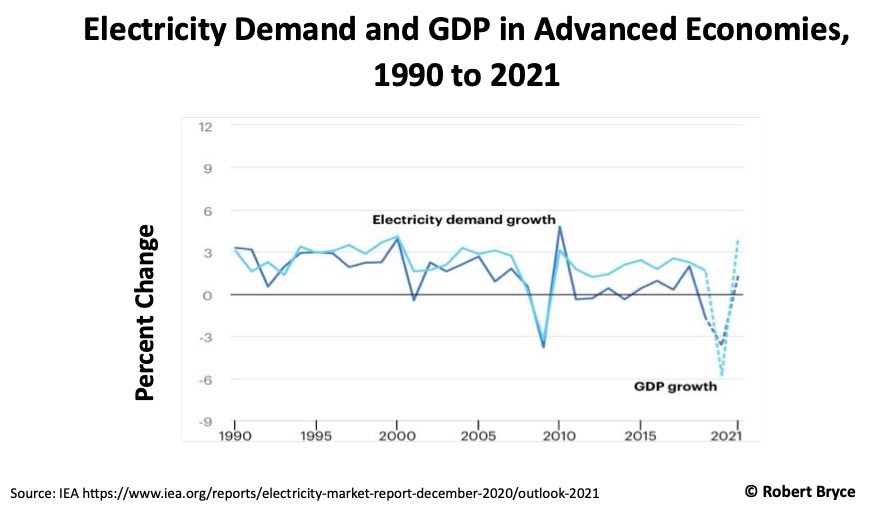

Electricity is an essential driver of economic growth. That is true in developing countries and advanced economies alike. In 2020, the IEA published two charts that demonstrated the close correlation between electricity demand growth and gross domestic product growth. As seen in the two graphics below, electricity use and GDP rise and fall in a close tango. (Note: the dark blue line is electricity demand growth. The light blue line is GDP growth, and the dashed lines are estimates.)

Figure 1

Figure 2

The transformative power of electricity has been the subject of numerous academic papers. In 2010, two academics at the University of Karachi published a paper that examined the “causal relationship between energy consumption and economic growth” in Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan. The analysis studied data between 1971 and 2008. While the analysis did not focus specifically on electricity, the conclusion of the authors, Kashif Imran and Masood Mashkoor Siddiqui, was clear: “Energy serves as an engine of economic growth and economic activity will be affected in the result of changes in energy consumption…GDP is basically determined by energy.” In 2014, two Turkish researchers, Yilmaz Bayar, and Hasan Alp Ozel, analyzed about two dozen published papers on electricity and economic growth. They found “unidirectional causality between electricity consumption and economic growth.”

While electricity drives economic growth, it is also clear that greater wealth increases electricity consumption. Energy writer Roger Andrews spotlighted this bi-directional effect of wealth and electrification in a 2015 study in which he concluded that in developing countries, “wealth creates electricity and not the other way round. There is no question, however, that once a country gains wealth it cannot sustain it without electricity. When the electricity disappears, the wealth goes with it.”

Another way to understand the correlation between electricity use and wealth is to look at nighttime luminosity—that is, the amount of light emitted by a region at night. In 2010, William Nordhaus, an economist at Yale University, published a paper that determined nighttime luminosity—measured by using images captured by satellites orbiting the Earth—has a close correlation with personal incomes. Nordhaus, who won the 2018 Nobel Prize in Economics, determined that luminosity is not particularly effective for analysing wealthy countries. But it is useful in analysing wealth in developing countries where traditional statistical information is not readily available. In 2012, three researchers from the National Bureau of Economic Research used a similar technique in their paper titled, “Measuring Economic Growth From Outer Space.” That paper concluded that nighttime luminosity provides “a very useful proxy for GDP growth over the long term and also tracks short-term fluctuations in growth.”

The punchline here is obvious: increased electricity use fosters economic growth, which, in turn, means better living conditions for humans. Electricity use also provides a reliable barometer for the health and wealth of individuals and societies. The IEA has called electricity “crucial to human development” and has said that electricity use is “one of the most clear and undistorted indications of a country’s energy poverty status.” Put another way, electricity bolsters economic growth and economic growth bolsters electricity demand. Together, those things help people escape poverty. As Paul Collier, the author of The Bottom Billion: Why the Poorest Countries are Failing and What Can Be Done About It, famously put it, “Growth is not a cure-all, but lack of growth is a kill-all.”

While people in the United States and other wealthy countries have come to expect cheap, abundant, reliable electricity as a birthright, the IEA recently estimated that about 800 million people still have no access to electricity. But that figure does not account for the billions of people who only use small quantities of power. Nor does it provide context for the challenge facing policymakers.

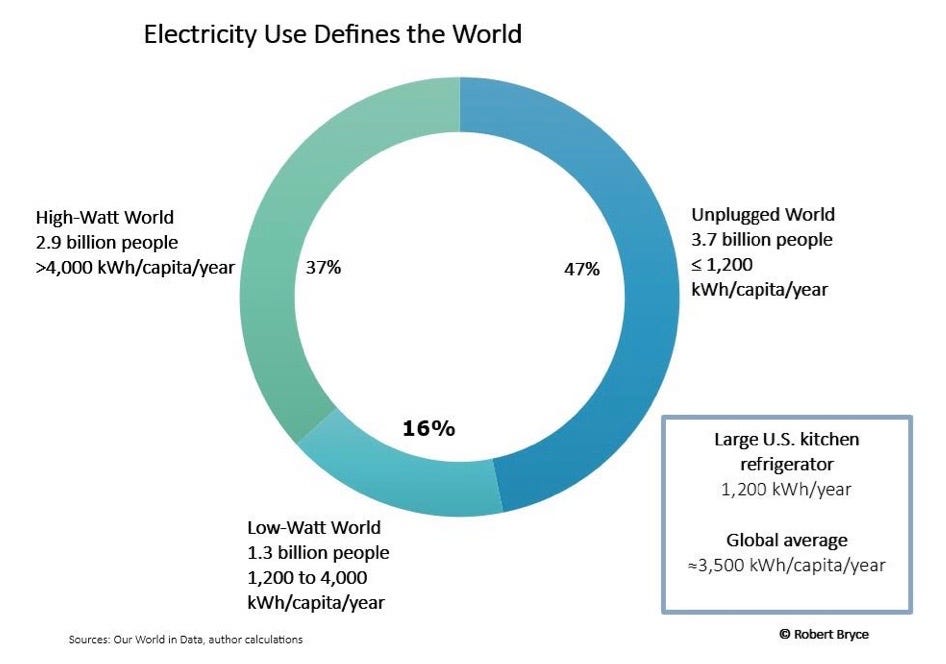

To get a better focus on the vast disparity in global electricity use, I needed good figures for per capita electricity use. Finding no recent sources, I devised a method to get those numbers. My methodology was simple. I used country-level 2021 population numbers published by Our World in Data. I combined the population data with 2021 electricity generation figures from the same source. I then trifurcated the global population into three segments: the Unplugged World, the Low-Watt World, and the High-Watt World. I did so using these demarcations:

The “Unplugged” countries, where per capita electricity use is less than 1,200 kilowatt-hours per year.

The “Low-Watt” countries, where per capita electricity use is between 1,200 and 4,000 kilowatt-hours per year.

The “High-Watt” countries, where per capita electricity use exceeds 4,000 kilowatt-hours per year.

Figure 3

Those demarcations were chosen on purpose. The 1,200 kilowatt-hour-per-year was used as the cutoff for the Unplugged World because that is the average electricity consumption level in India, a country that has long been plagued by energy poverty. Although India has made great strides in recent years, the country still struggles to increase electricity availability and consumption.

To put that quantity in perspective, 1,200 kilowatt-hours of use per person is about one-third of the global average. It is also about the same amount of energy as what is used annually by a large kitchen refrigerator in the United States. As seen in the graphic above, about 3.7 billion people—about 47% of all the people on the planet—are now living in the Unplugged World. The Unplugged countries include El Salvador, the Philippines, and Bolivia.

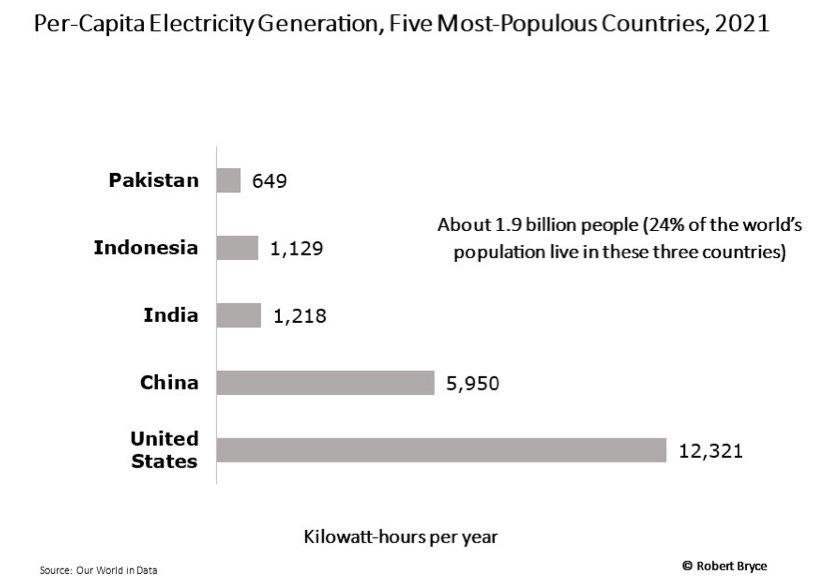

Figure 4

Further, as shown in Figure 4, three of the world’s most populous countries are in the Unplugged World. Together, Pakistan, Indonesia, and India contain about 1.9 billion people. That means that about 24% of the world’s population is, effectively, Unplugged. In those three countries, per capita electricity use is far less than one-third of the global average of 3,500 kilowatt-hours per year.

The Low-Watt designation applies to the locales where per capita annual electricity use is between 1,200 kilowatt-hours and 4,000 kilowatt-hours. About 1.3 billion people—approximately 16% of the world’s population—are living in the Low-Watt World. The countries in this segment include places like Brazil, Argentina, and Turkey. These locales are not necessarily poor, but they are not among the wealthiest.

Finally, about 2.9 billion people, or 37% of the world’s population, live in the High-Watt World, the segment where per capita electricity use is 4,000 kilowatt-hours or more, per year. The countries in this segment include the United States, Britain, Germany, and Israel.

Four thousand kilowatt-hours of electricity use per annum is a key demarcation line because that quantity of energy is considered the minimum for living a long, high-quality life. In 2000, Alan D. Pasternak, a chemical engineer who worked at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, published a paper that analysed per capita electricity consumption in 60 countries and then correlated that electricity use with indicators of human health and welfare. Using data from the United Nations Human Development Index (“HDI”), which ranks countries based on measures like life expectancy, nutrition, health, mortality, poverty, education, and access to safe water and sanitation, Pasternak calculated a score for each country, with 1.0 being the maximum. Pasternak found that less than 15% of the world’s population enjoyed an HDI of 0.9 or greater. Further, Pasternak wrote that “there is a threshold at about 4,000 kilowatt-hours per capita, corresponding to an HDI of 0.9 or greater, in the relationship between HDI and electricity consumption.” In other words, Pasternak (who died in 2010) found that the 4,000 kilowatt-hours mark was the key dividing line.

“As electricity consumption increases above 4,000 kilowatt-hours, no significant increase in HDI is observed,” he wrote. Conversely, he found that the lower the electricity consumption, the lower the HDI. In a summary of his findings, Pasternak was blunt, saying that neither the HDI nor the economic output “of developing countries will increase without an increase in electricity use.” Pasternak continued, “What is of interest is the fact that large populations of the world are significantly below the electricity threshold level associated with a Human Development Index typical of developed countries.” Those low rankings, he continued, “reflect short life expectancy and low educational attainment—measures that are far more compelling than the purely economic metrics usually associated with energy consumption.” Therefore, he said, “there is a compelling need for increased energy and electricity supplies in developing countries.”

The essential point of Pasternak’s paper is this: small amounts of electricity are not effective at alleviating poverty. Sure, small amounts of power are better than nothing. But Pasternak’s paper shows that if the world’s poverty-stricken people are going to come out of the dark and into modernity, we are going to need vastly more electricity than what is now being produced.

Why is there such a vast disparity in electricity use around the world? There are many ways to explain the reasons for the disparity. Before doing so, it is essential to understand who suffers the most due to the lack of electricity.

I also made a short video about the paper. It’s on the ARC’s YouTube channel:

Please subscribe, share, and by all means, click that ♡ button.

Need a speaker for an upcoming event? Email me: robert (at) robertbryce.com

Check out the Power Hungry Podcast. My latest guest: Jimmy Glotfelty, a commissioner at the Texas Public Utility Commission, talking nuclear energy in Texas.

Finally, I was on the Rio Grande Foundation podcast, with my friend, Paul Gessing, talking about EV mandates. Check it out.

Excellent summary. Robert didn't have the space to point out that Michael Shellenberger, one of the ARC cofounders, wrote about the relationship between energy (not just electricity) and poverty in "Apocalypse Never: Why Environmentalism Hurts Us All."

Something that neither Robert nor Michael noted is that prosperity reduces fertility, so if you're worried about overpopulation, you should be gung-ho for energy. Last year, Japan had twice as many deaths as births. For the first time in its history, it's accepting legal permanent resident immigrants, mostly from China and Korea, on one condition: They must become farmers. European fertiliuty, including European Russia, is below replacement. But for immigration the United States would be below replacement.

Beyond land-use conflicts, there are inescapable physical reasons that the world's electrical system cannot run on renewables alone. In https://tupa.gtk.fi/raportti/arkisto/42_2021.pdf, Simon Michaux shows that the ell-electric all-renewable program promoted by the IEA would require five times more copper, ten times more nickel, 26 times more cobalt, ... than are known to exist in forms that can be exploited (and my estimates are more pessimistic). In the United States alone, the cost for batteries to provide firm power, assuming 100% charge-discharge efficiency, and not counting installation, would be more than four times total GDP every year. Pumped-storage would require 8,200 of Australia's Snowy 2.0 projects; we currently have forty. Analysis of data from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission shows that, statistically, Kansas is indeed as flat as a pancake. Towing rocks up mountains or abandoned mine shafts would require about 15 million devices. "Green Hydrogen" has end-to-end efficiency below 22%, and hydrogen poses intractable storage and safety problems (synthetic fuels make more sense).... If we must abandon coal and natural gas (and that's a big IF) then nuclear power is the only alternative.

Read a preprint of my new book "Where Will We Get Our Energy?" at http://vandyke.mynetgear.com/Whence-Energy.html

“There is no question, however, that once a country gains wealth it cannot sustain it without electricity. When the electricity disappears, the wealth goes with it.”

See; Germany