Vaclav Smil Calls Bullshit On Net Zero

The reclusive polymath calls it “wishful thinking” and “an impossible task.” Plus, U. of Michigan study says lack of Cu makes electrification of transportation “essentially impossible.”

In a 2019 interview, Vaclav Smil described himself as “just an old-fashioned scientist describing the world and the lay of the land as it is. That’s all there is to it. It’s not good enough just to say life is better or the trains are faster. You have to bring in the numbers.” (Emphasis added.)

Smil has been bringing the numbers for a long time.

A polymath who has written about 50 books, Smil has gained renown for his unflinching analysis of the world in which we live. I own a dozen of his books. My favorite is Creating the Twentieth Century. His influence on my work has been profound. Along with Jesse Ausubel, Smil made me understand the importance of power density, which has become a mainstay of my writing and analysis. (Smil wrote a book on the subject, aptly titled: Power Density: A Key to Understanding Energy Sources and Uses, published in 2015.)

Smil has also gained fame for his dismissive attitude toward the media. He gives very few interviews. And the few he allows are done almost exclusively by email. I know this myself. In 2022, he declined my invitation to come on the Power Hungry Podcast, saying:

I get constant invites for podcasts and video appearances, but accepting one or two would invite a flood, and if I preferred doing that I could have turned myself into a TV talking head (a medium I detest even more than the Net). Privacy is a great value, utterly incomprehensible in Kardashianized America, but I remain an old-fashioned European: one attribute of that is that (contrary to my son's advice: just delete!) I feel obliged to answer all e-mails I get and to explain why I do or do not do something. As I always say, there is surely no shortage of people in America who want to hear themselves talking or displaying themselves on TV.

From there, our email conversation focused on bird feeders and how to defeat squirrels. I haven’t been in touch with him since.

I provide that preamble because it’s essential to put Smil into context. He’s the anti-Kardashian. He is also a slayer of the bullshit about energy and power that has become accepted wisdom in media, academia, and among politicians and policymakers.

The notion of net zero is among the most pungent examples of that caca de toro. In 2021, the Biden Administration released a “long-term strategy” that it claimed would allow the U.S. to reach “its ultimate goal of net-zero emissions no later than 2050.” It continued, saying achieving net zero “will keep a 1.5°C limit on global temperature rise within reach and prevent unacceptable climate change impacts and risks.” In addition, 21 states and about 100 U.S. cities have declared that they will achieve either net zero, or 80% reductions in greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. The total population of those 21 states is about 187 million people.

Smil isn’t having any of the net zero silliness.

In a 48-page report published last month by the Fraser Institute, titled “Halfway Between Kyoto and 2050: Net Zero Carbon Is a Highly Unlikely Outcome,” Smil spotlights the enormous scale of global energy use, the slow pace of energy transitions, labor shortages, and the massive cost of attempting to eliminate hydrocarbon use. In every part of his report, Smil brings the numbers. In fact, he brings them by the truckload. Here’s a (rather long) excerpt:

In terms of final energy uses and specific energy converters, the unfolding transition would have to replace more than 4 terawatts (TW) of electricity-generating capacity now installed in large coal- and gas-fired stations by converting to non-carbon sources; to substitute nearly 1.5 billion combustion (gasoline and diesel) engines in road and off-road vehicles; to convert all agricultural and crop processing machinery (including about 50 million tractors and more than 100 million irrigation pumps) to electric drive or to non-fossil fuels; to find new sources of heat, hot air, and hot water used in a wide variety of industrial processes (from iron smelting and cement and glass making to chemical syntheses and food preservation) that now consume close to 30 percent of all final uses of fossil fuels; to replace more than half a billion natural gas furnaces now heating houses and industrial, institutional, and commercial places with heat pumps or other sources of heat; and to find new ways to power nearly 120,000 merchant fleet vessels (bulk carriers of ores, cement, fertilizers, wood and grain, and container ships, the largest one with capacities of some 24,000 units, now running mostly on heavy fuel oil and diesel fuel) and nearly 25,000 active jetliners that form the foundation of global long-distance transportation (fueled by kerosene)... On the face of it, and even without performing any informed technical and economic analyses, this seems to be an impossible task given that:

We have only a single generation (about 25 years) to do it;

We have not even reached the peak of global consumption of fossil carbon;

The peak will not be followed by precipitous declines;

We still have not deployed any zero-carbon large-scale commercial processes to produce essential materials; and

The electrification has, at the end of 2022, converted only about 2 percent of passenger vehicles (more than 40 million) to different varieties of battery- powered cars and that decarbonization is yet to affect heavy road transport, shipping, and flying.

None of this will come as a surprise to students of energy history as global energy transitions have always been protracted affairs. (Emphasis added.)

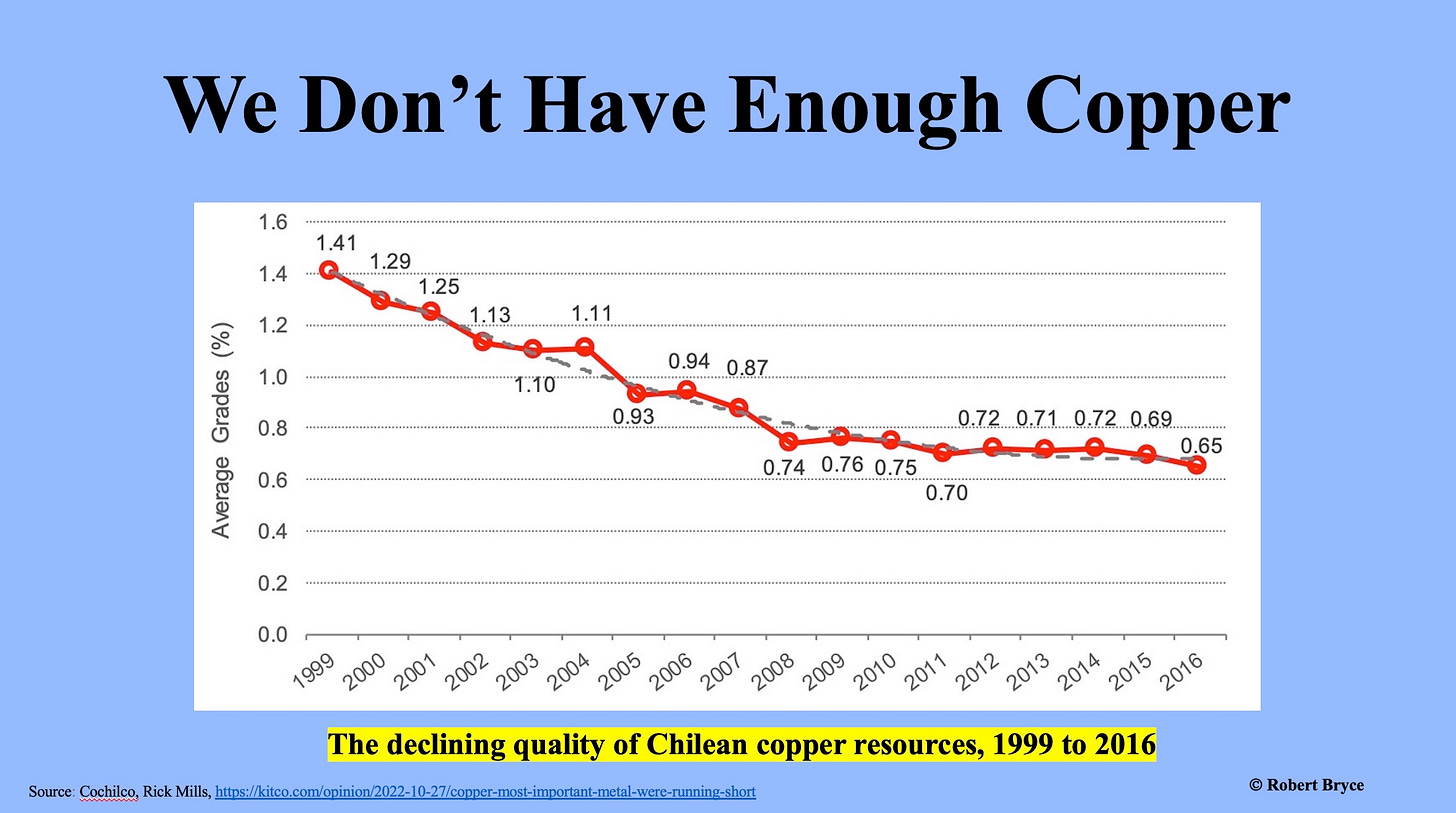

Smil takes a deep dive into the metals and minerals needed to displace hydrocarbons, including a special focus on copper. Again, he brings the numbers:

Replacing today’s 1.35 billion light-duty gasoline and diesel vehicles with EVs and supplying the expanded market (estimated at 2.2 billion cars by 2050) would thus require nearly 150 million tons of additional copper during the next 27 years. That is an equivalent of more than seven years of today’s annual copper extraction for all of the metal’s many industrial and commercial uses...Copper offers a stunning example of these environmental externalities. The metal content of exploited copper ores from Chile, the world’s leading source of the metal, has declined from 1.41 percent in 1999 to 0.6 percent in 2023, and further quality deterioration is inevitable. Using the mean richness of 0.6 percent means that the extraction of additional 600 million tons of metal would require the removal, processing, and deposition of nearly 100 billion tons of waste rock (mining and processing spoils), which is about twice as much as the current annual total of global material extracted including harvested biomass, all fossil fuels, ores and industrial minerals, and all bulk construction materials. Extracting and dumping such enormous masses of waste material exacts a very high energy and environmental price.

Smil also exposes the insane cost of net zero. Using a McKinsey study that estimated net zero would cost about $275 trillion between 2021 and 2050, Smil says that the actual costs will be at least 60% higher due to the inevitable cost overruns. Adding in those overruns, he writes:

Would raise McKinsey’s estimate of the cost of global decarbonization to $440 trillion, or nearly $15 trillion a year for three decades, requiring affluent economies to spend 20 to 25 percent of their annual GDP on the transition. Only once in history did the U.S. (and Russia) spend higher shares of their annual economic product, and they did so for less than five years when they needed to win World War II.

The U.S. currently has a GDP of about $25 trillion. If we assume net zero will cost 20% of our GDP, the U.S. would have to begin spending about $5 trillion per year on decarbonization efforts. For reference, the 2025 budget for the Department of Defense will be about $850 billion. Needless to say, allocating $5 trillion per year — or even a quarter of that sum on decarbonization — will not happen.

Smil’s entire report is a must-read document for anyone interested in a sober look at our energy and power systems. I will conclude with the sentence that he uses in his summary:

To eliminate carbon emissions by 2050, governments face unprecedented technical, economic and political challenges, making rapid and inexpensive transition impossible.

Copper Needed For Switch To EVs Is “Essentially Impossible For Mining Companies To Produce”

There are many reasons we won’t all be driving Teslas or Ford Lightnings anytime soon. The list includes high purchasing cost, time needed to charge, limited range, and the lack of recharging stations. But the more fundamental reason is simple: There isn’t enough copper.

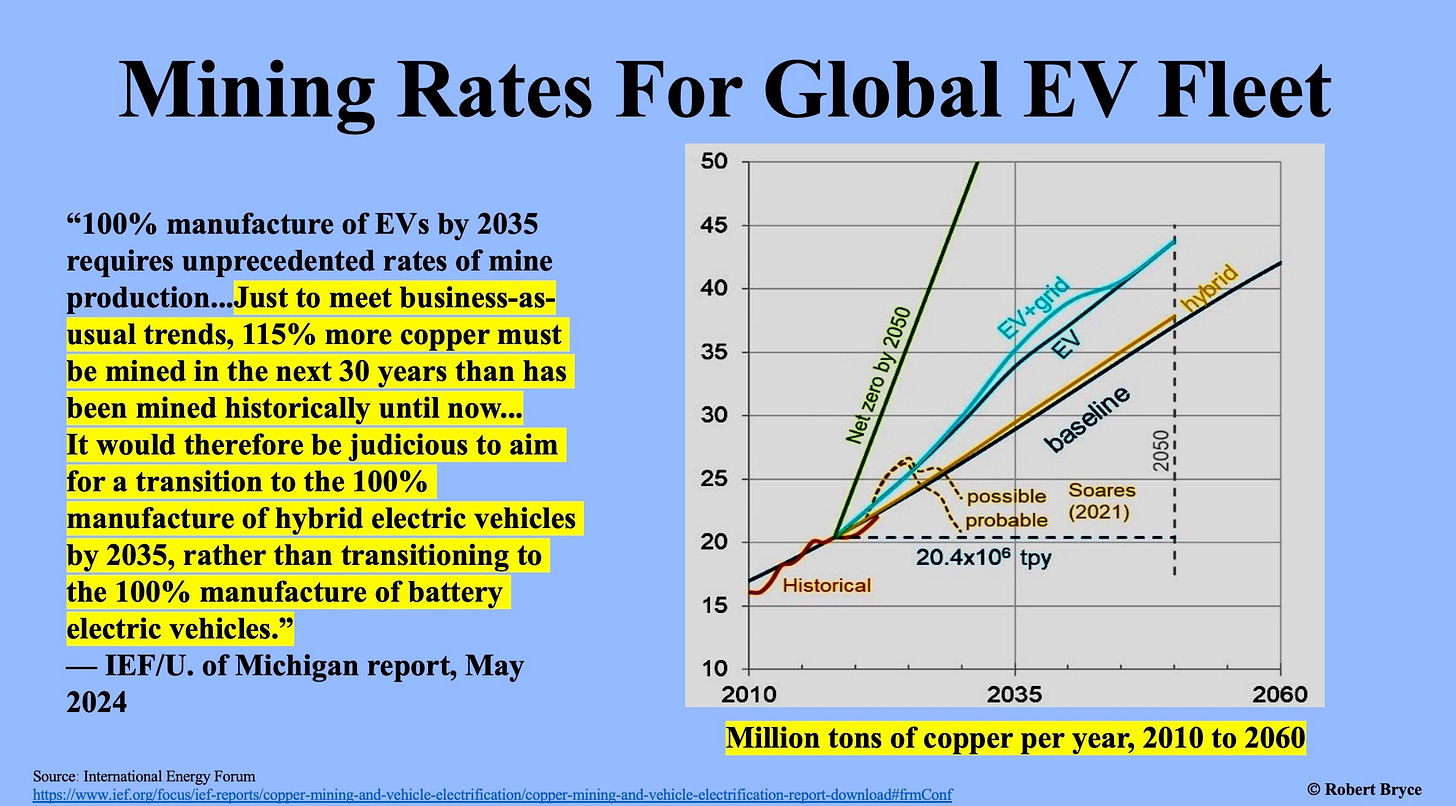

Earlier this month, a study done by researchers at the University of Michigan for the International Energy Forum found that the amount of copper needed to electrify transportation is according to Adam Simon, an author of the study, “essentially impossible for mining companies to produce.”

In their report, “Copper Mining and Vehicle Electrification,” Simon and his co-author, Lawrence Cathles of Cornell University, explain that an EV requires about 200 pounds of copper. That’s five times what’s needed for a conventional vehicle. As a press release on the report explains, “The study examined 120 years of global data from copper mining companies, and calculated how much copper the U.S. electricity infrastructure and fleet of cars would need to upgrade to renewable energy. It found that renewable energy’s copper needs would outstrip what copper mines can produce at the current rate.”

Simon and Cathles found that to supply alt-energy and EVs would outstrip what copper mines can produce at the current rate. Between 2018 and 2050, the world will need to mine 115% more copper than has been mined in all of human history up until 2018 to meet current copper needs, and that sum doesn’t include the over-hyped “energy transition.” Simon said the study shows we need a “complete mindset change about mining among environmental groups and policymakers.”

Several previous studies have come to the same conclusion. In 2019, I published a piece on this topic in The Hill. I used an analysis by Richard Herrington, the head of earth sciences at the Natural History Museum in London, to calculate how much copper and other metals would be needed to electrify U.S. transportation. In June 2019, Herrington and his colleagues sent a letter to the British government that calculated the amount of metals that would be needed to convert all the United Kingdom’s 31 million motor vehicles to electric drive. I wrote:

The U.S. has about 276 million registered motor vehicles, or roughly nine times as many vehicles as the U.K. Thus, if Herrington’s numbers are right, electrifying all of U.S. motor vehicles would require roughly 18 times the world’s current cobalt production, about nine times global neodymium output, nearly seven times global lithium production, and about four times world copper production. (Emphasis added.)

In 2021, Simon Michaux, an associate professor of geometallurgy at the Geological Survey of Finland, published a 1,000-page report about the mining required if the world attempts to quit using hydrocarbons. He estimated that the amount of copper needed to produce one generation of technology units to phase out fossil fuels would be 4.3 billion tons. At current rates of production, that much copper would take 180 years. (Michaux was on the Power Hungry Podcast in November 2022. The transcript is here.) One of Michaux’s key quotes agrees with Smil’s point in his net-zero paper about the declining quality of copper ore. Michaux said, “We’re not running out of copper ore. The entire Andes mountain range is one big giant copper deposit. What we’ve got is a very low-grade ore, where all types and grades [have] been decreasing. Where we are facing challenges is in `our ability to extract that copper.”

The need for copper is only part of the boom in global commodities. Copper prices have surged since the beginning of the year and as the price of that metal increases, so, too, will the cost of attempting to electrify everything. I’ll be writing more about commodities over the coming weeks.

Please click that ♡ button. And please subscribe and share. Thanks y’all.

I'd like Vaclav Smil or someone to bring their numerical talents to the largely ignored environmental costs of attempting Net Zero. For instance, destruction of the Mojave, Colorado, and Sonoran Deserts in California, Nevada, and Arizona by vast solar farms has been happening over at least two decades. This is about money not the environment. These States and the rest of the USA need to recognize what's happening. A desert road trip along I-10, I-15, Hwys 14, & 40 will show what damage can be seen from easily accessible paved roads. Google Earth displays the full extent of the destruction. A solar farm starts by clearing the ground of plants and animals, the area is fenced-off, and roads and panels are installed. It's a nearly complete destruction of a fragile environment whose impact will last for centuries.

"There are many reasons we won’t all be driving Teslas or Ford Lightnings anytime soon. The list includes high purchasing cost, time needed to charge, limited range, and the lack of recharging stations. But the more fundamental reason is simple: There isn’t enough copper."

The Nut Zeroes know that. They don't care. The ones that don't know don't care, either. The still more fundamental reason we won't all be driving EVs is because we're not intended to go anywhere. We're intended to sit in our 15-minute cities and exist as livestock on UBIs. That's for those who survive the shutdown of fossil fuel power. The rest are intended to die: a 500 million global population is the goal. Nut Zero, when you get all the way down, is a death cult of self-hating, life-hating sociopaths.