Wisconsin Town Fights Big Solar (And Climate Corporatism)

Chicago-based Invenergy wants to cover about seven square miles of the tiny town of Christiana with solar panels. The town and local residents are suing to stop it.

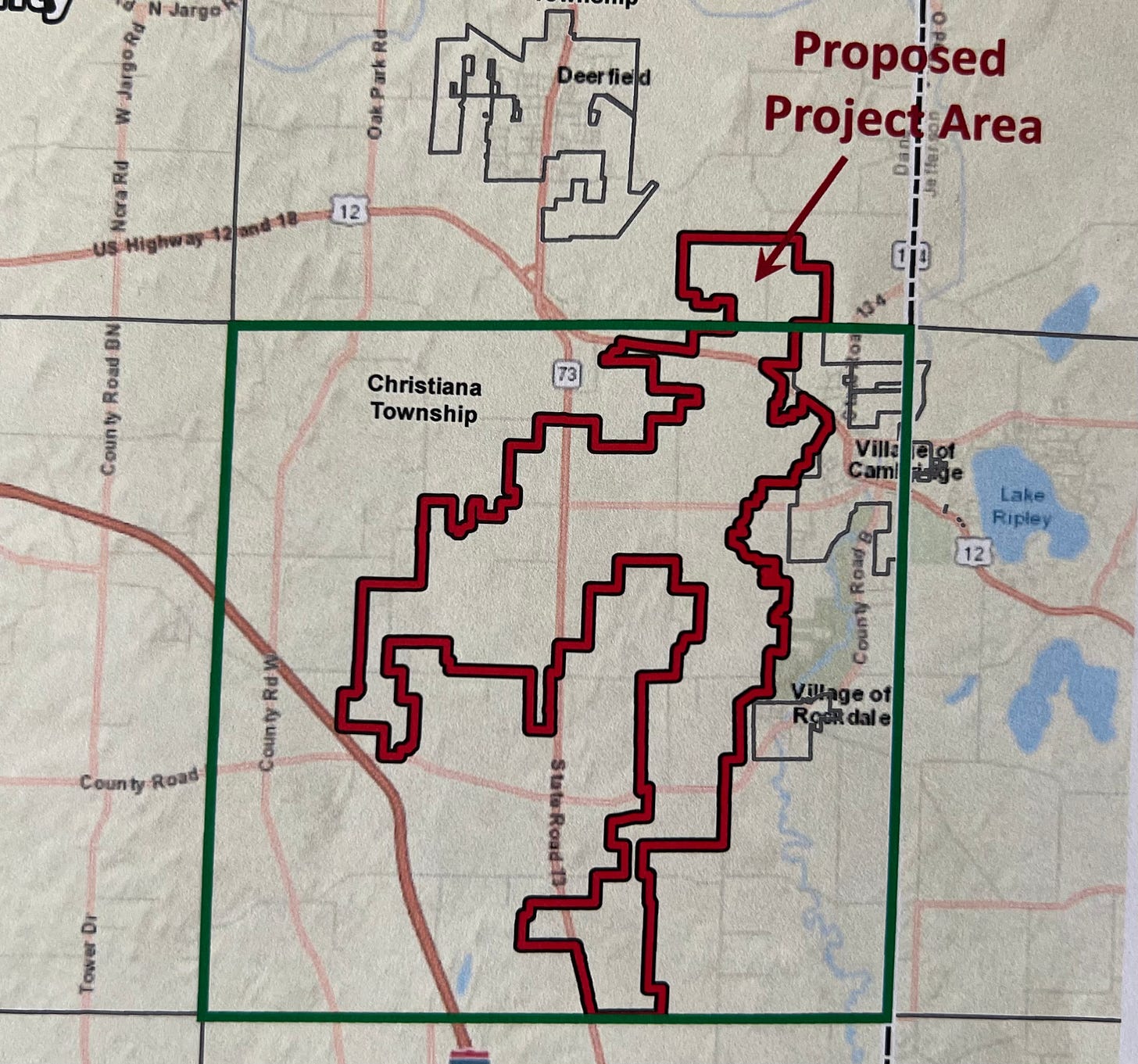

When I arrived at the Christiana Town Hall yesterday afternoon, Mark A. Cook, the town chairman, and two local landowners, John Barnes, and Roxann Engelstad, were ready and waiting. They had multiple maps and charts showing the footprint and details of Invenergy’s proposed 300-megawatt Koshkonong Solar Energy Center.

Cook got right to the point. Christiana, he said, has been “based on agriculture since people settled here. This project will completely kill ag in this town for generations.” The solar project is targeting “our very best farmland. It’s not like they are taking the crap land. This is the cream of the crop.” He went on, saying that the company is targeting farmland because it’s relatively flat and therefore will be easy to cover with panels. In addition, Christiana is near a gas-fired power plant that is connected to the high-voltage transmission grid. That location will make it easy for the proposed solar project to get its electricity onto the grid.

About 1,800 people live in Christiana, which is located 70 miles west of Milwaukee. It sits amid picturesque rolling hills and farms that mostly grow corn and soybeans. The landscape is marked with thickly wooded patches of trees and shrubs that have grown back in the areas that aren’t under the plow. The soil is a rich, dark brown. Under cloudy skies, the tilled land looks almost black.

Cook, who is also the president of the Cambridge Area Fire and EMS Commission, told me Christiana operates on a budget of about $3.8 million. It has already spent about $200,000 in legal fees fighting the Invenergy project. It has filed one lawsuit to stop the $650 million project and will soon file another suit against the Wisconsin Public Service Commission. The town is claiming the agency violated the Wisconsin Constitution and the commission’s own rules when it granted a permit for the project last year. More about the legal details in a moment.

The fight in Christiana provides yet another snapshot of the land-use conflicts over renewables that are raging all across the country. People like Cook, Barnes, Engelstad, and the other people in Christiana, are not NIMBYs, the slur that project developers and many climate activists like to use when describing people who are fighting big renewable projects.

Instead, their efforts to protect Christiana and its farmland from the energy sprawl that comes with large-scale renewable projects are directly in line with the views of an overwhelming majority of Americans. In March, a new media outlet called Heatmap (“focused on the biggest story in the world: the great climate and energy transition”) published the results of a poll of 1,000 adult Americans.

The poll, which included people from all 50 states, found that “79% of Americans said that new renewable energy should be rolled out ‘slowly’ rather than ‘quickly’ and that the conservation of land and wild animals should be prioritized above rapid greenhouse-gas reductions.”

Heatmap’s Robinson Meyer, continued, explaining that “only 21% of Americans agreed with the statement that ‘we should roll out renewable energy quickly to lower emissions as fast as possible, even if it means harming natural land or wild animals.’” Meyer added a line that you won’t read in the New York Times or NPR: “In other words, you don’t necessarily need recourse to astroturfing schemes or secret fossil-fuel connections to explain why so many Americans oppose new renewable projects.”

“79% of Americans said that new renewable energy should be rolled out ‘slowly’ rather than ‘quickly’ and that the conservation of land and wild animals should be prioritized above rapid greenhouse-gas reductions…In other words, you don’t necessarily need recourse to astroturfing schemes or secret fossil-fuel connections to explain why so many Americans oppose new renewable projects”

Indeed, as can be seen in the Renewable Rejection Database, huge numbers of rural Americans from Maine to Hawaii are opposing wind and solar projects. Since 2015, local communities and jurisdictions have rejected or restricted wind or solar projects nearly 500 times. Rural Americans are fighting these projects because they are concerned about their property values, and rightly so. A 2020 study in Rhode Island found that prices of homes located close to solar projects went down by as much as 7%. A study released last month by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory concluded that solar projects can reduce the value of nearby properties by as much as 5%.

The story I heard yesterday in Christiana echoes what I’ve heard from people in dozens of other communities over the last decade. The scenarios are almost always the same: a big, out-of-state renewable energy company comes into a rural community, quietly obtains leases from a handful of large (often absentee) landowners, and then lets the local government know that it plans to cover big swaths of land with wind turbines or solar panels. Once the news spreads, residents get organized to fight the projects. They are always outgunned. They never have enough money and thus, can’t match the financial muscle of the big corporations. Sometimes they are successful in keeping the projects at bay. Sometimes they are not.

Christiana residents face a formidable foe in Invenergy. The company, which is controlled by billionaire Michael Polsky, (estimated net worth: $1.5 billion) is the world’s largest privately held renewable energy company. Invenergy has gained a reputation as one of the most aggressive and litigious companies in the renewables business. Last year, the company sued Worth County, Iowa as part of an effort to force the county to accept a wind project the county doesn’t want. The company also sued Fulton Township, Michigan last year, shortly after it denied a permit that would have allowed the company to 12 wind turbines in the township.

Julie Kuntz, who describes herself as “a fifth-generation Iowa farm girl” told me last year on the Power Hungry Podcast, that Invenergy has been using “nefarious tactics” to try to convince rural landowners in Iowa to sign leases. (That interview is also available here.) Kuntz, a resident of Grafton, Iowa, said she had received emails from one of Invenergy’s lawyers that she felt were aimed at intimidating her. “That’s kind of the way that this company works...is by intimidation.”

Now back to Koshkonong. Invenergy’s proposed project will cover about 6,400 acres or 10 square miles. As can be seen in the map above, if the project is built, it will cover about a third of the town of Christiana. In addition to the solar panels, which could cover some 7.2 square miles of farmland, the project plans also include a 165 MW (667 MWh) battery storage system that, if built, would be located a few hundred feet from a local elementary school.

In May 2022, the Wisconsin PSC granted what’s known as a certificate of public convenience and necessity to Invenergy. That permit effectively prevents Christiana from enforcing any zoning rules that would stop the project. But here’s the rub: Invenergy got the permit from the PSC, but it plans to sell the Koshkonong solar project to two utilities: Milwaukee-based WEC Energy Group and Madison Gas and Electric.

Frank Jablonski, a Madison-based lawyer who is representing Engelstad and her husband, Edward Lovell, in their lawsuit against the PSC, told me by phone that what the PSC is doing on the Koshkonong project is allowing Invenergy and the two utilities that plan to buy it, to “circumvent state rules that would require more stringent analysis.” He added that if WEC Energy Group and Madison Gas and Electric had sought to build the project themselves, they would have had to go through a much more stringent regulatory and environmental review process.

In short, what’s happening in Christiana is yet another example of climate corporatism. Earlier this month, I wrote about Jamie Dimon, the head of America’s biggest bank, J.P. Morgan, who recently suggested that governments should use the power of eminent domain more frequently so that more wind and solar projects could be built. Dimon failed to mention that his bank is one of the biggest players in the lucrative business of tax equity finance, a $20-billion-per-year industry that plays a pivotal role in the development of wind and solar projects. As I explained in that piece, climate corporatism is the use of government power to increase the profits of big corporations at the expense of consumers—and in particular, at the expense of small (and mostly rural) landowners—in the name of climate change.

The use of government power to allow Invenergy and the two utilities to make more money is clearly what is happening in Christiana. Indeed, that’s one of the main claims in Engelstad’s case against the PSC. It says that by giving Invenergy the certificate of public convenience and necessity, the PSC is allowing the utilities to “evade detailed regulatory disclosures and analysis that would be required” under Wisconsin state law. It also claims that Invenergy’s plan to sell the Koshkonong project to the two utilities allows it to gain a “competitive advantage over potential bona fide merchant developers, violating state policy favoring competition that the PSC is charged with implementing.”

One of the many opponents of the Koshkonong project is Carissa Lyle, who lives in a century-old farmhouse in Christiana with her husband, Nathan, and three small children. If built, the Koshkonong project would surround their three-acre property on three sides. Last year, Lyle, who is also the town clerk, sent me an email. She wrote: “To anyone reading this who wants to dismiss our concerns and fears, I ask you to put yourself in our shoes...We don’t know what our family’s future will look like. As of right now, we face some difficult decisions. If this project is approved, we must decide if we want to risk staying at this location. If we decide it’s not worth the safety of our family and we need to move, will we be able to sell? And if we sell, how much of a loss will be taking?”

On Wednesday afternoon, I met Lyle in person at the Christiana Town Hall. We talked while her three young children, Carter, Miles, and Brinley raced among the tables and chairs in the town hall’s meeting room. “This is about class,” she told me. “It’s big landowners and cities and big business trying to tell us what to do.”

How stupid is to put solar in a part of the country with months of snow and rain? I’d rather have the food than the totally unreliable power. Build a nuke plant that covers less grown and produces lots of reliable power instead.

When are “the powers that be finally admit that a nuclear, hydro, fossil fuel mix is the ONLY wave of the future!!!