3 Reasons Why Natural Gas Prices Will Go Up, 3 Stocks To Buy If They Do, And 3 Reasons Why Natty Could Stay “Perpetually Cheap”

Will AI, LNG exports, and increased power burn mean higher prices?

In September 1918, a few miles north of Amarillo, drillers working on the Hapgood-Masterson No. 1 hit natural gas at 2,605 feet. The well, which produced 5 million cubic feet of gas per day, was the first to tap what would become known as the Panhandle-Hugoton Gas Field, a monster gas-producing region stretching some 275 miles long and as much as 90 miles wide.

The Texas Panhandle was soon producing so much gas that the city of Amarillo spent $60,000 on an advertising campaign to attract customers. The offer: free gas for five years to any industrial outfits who moved to Amarillo.

Free wasn’t good enough. Not a single company took the city up on the offer. More than a century later, free still isn’t good enough.

On May 6, 2024, next-day natural gas prices at the Waha trading hub in Pecos County, Texas, hit negative $2.72 per million Btu. Thus, the companies sending their gas through Waha had to pay $2.72 per MMBtu to get rid of their fuel. That wasn’t unusual. For the entire month of April, gas at Waha sold for a negative $0.26 per MMBtu.

Why are Permian gas producers paying to get rid of their gas? They are being overwhelmed by “associated gas” — the term for methane that comes out of wells with oil — and there aren’t enough pipelines to handle all that gas.

In fact, today, the Permian produces about 18 billion cubic feet of gas per day, and it produces that staggering quantity of fuel even though not a single driller in the region is drilling for gas. Put short, there’s too much gas and too little pipeline capacity to move it to market. Furthermore, the Permian gas glut will likely worsen over the coming years as the wells in the prolific hydrocarbon basin get older. Why? As the oil in the Permian wells gets depleted, the wells will produce increasing volumes of gas, and there’s not enough pipeline capacity in the works to move all of it to market.

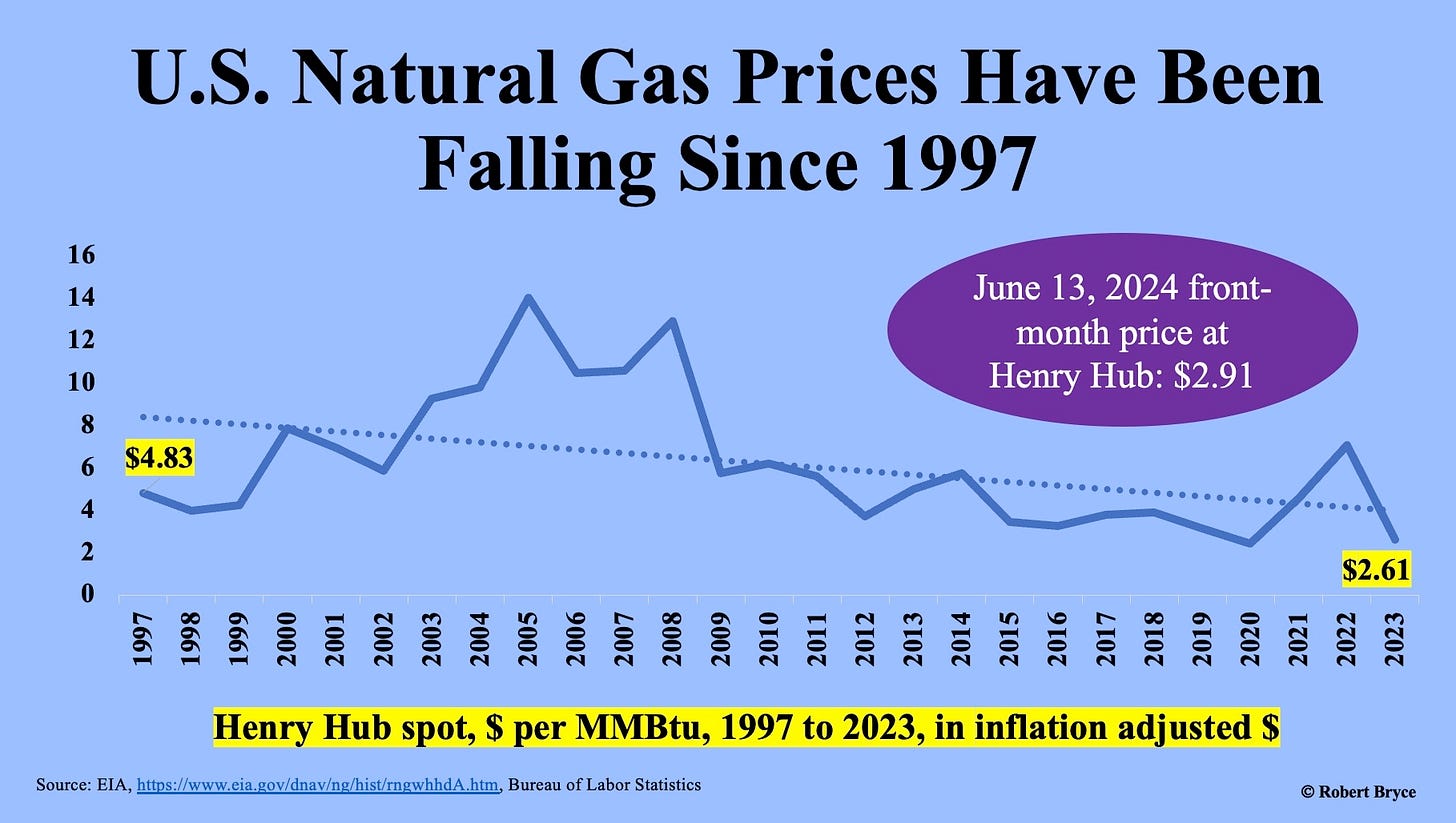

As I explained a few weeks ago in “Natty Nation,” the U.S. is a gas superpower. We produce and use more gas than any other country on the planet. And that cheap gas has benefited the entire economy. This ongoing abundance of natural gas is one of many reasons the U.S. economy has been so resilient. As seen in the graphic below, the inflation-adjusted price of natural gas has been falling since 1997.

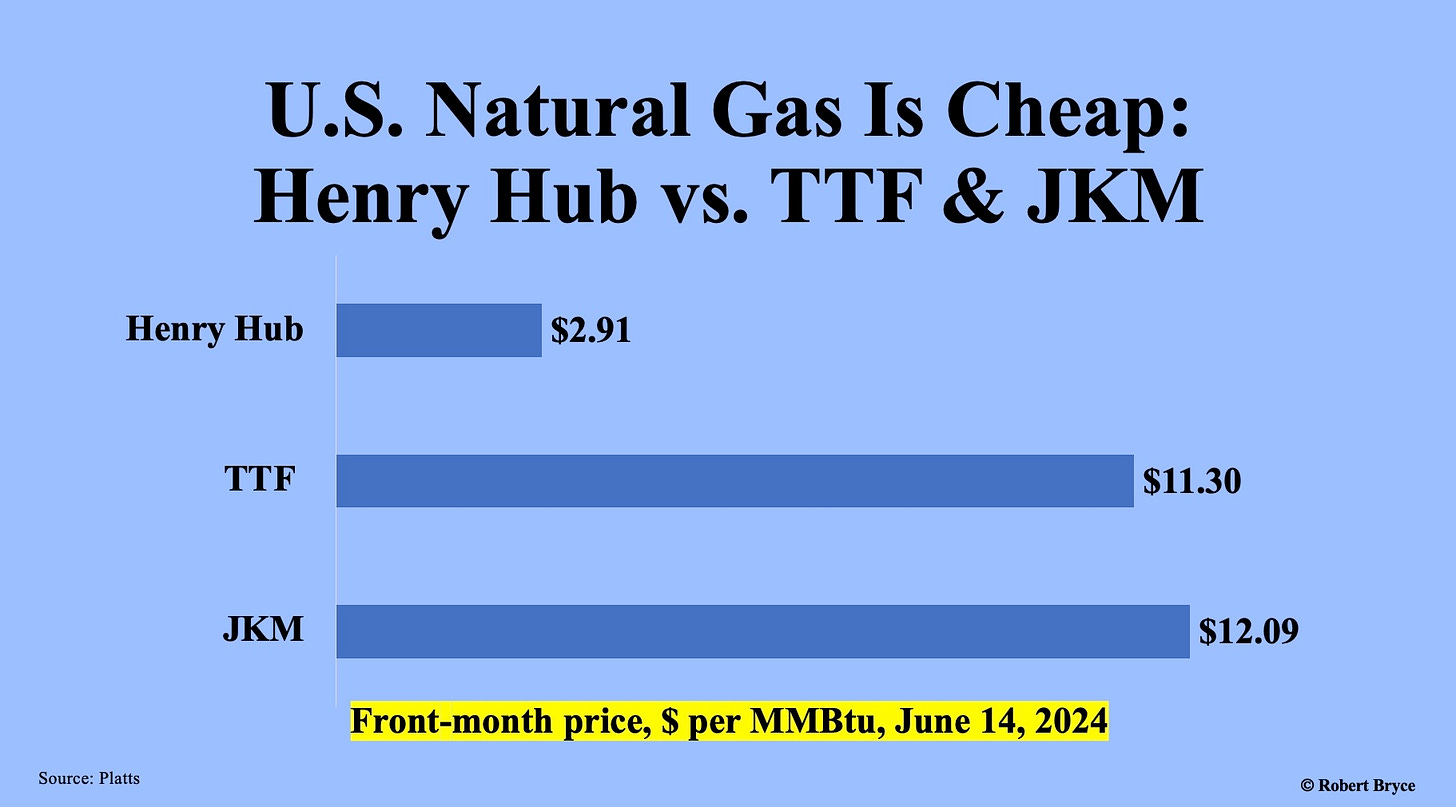

At the same time the Permian is being flooded with gas, Europe is desperately trying to find more methane to replace the fuel it used to get from Russia. The U.S. has a significant price advantage over the rest of the world. Natural gas traded at the benchmark Henry Hub terminal in Louisiana sells for less than $3 per MMBtu. That’s about a quarter of the price being paid by consumers who buy at the TTF trading hub in the Netherlands or in the form of LNG delivered into the Asian market, which is priced by the JKM marker.

But will U.S. gas stay cheap? Prices have been trending upward since March. Will surging electricity demand from the data centers needed for artificial intelligence, increased LNG exports, and rising power demand from things like EVs and heat pumps create a tight market and lead to higher prices? Put short, is it different this time? And if so, which publicly traded gas drillers should investors consider buying?

I’ve been thinking about those questions for several weeks. I’ve posed them to more than a dozen people in the energy industry. (I’ve also had about two dozen conversations with my older — and smarter — brother, Wally Bryce, about these questions. Wally is a CPA and avid stock market watcher.) The consensus of all those conversations: there was no consensus. About half of the people I talked to were bullish, and the other half were bearish. Thus, here are three reasons why natural gas prices may go up, the three companies that could make big profits if they do, and three reasons why natural gas, as one Colorado-based friend who’s worked in the gas industry for decades told me — will stay “perpetually cheap.”

Before I continue, here’s a quick disclaimer, which I stole from a fellow Substacker, Quoth The Raven, who published a delicious takedown last month of beleaguered investor Cathie Wood. Raven said:

This post represents my opinions only. In addition, please understand I am an idiot and often get things wrong and lose money. I may own or transact in any names mentioned in this piece at any time without warning. (Emphasis added.)

I’ll add to that disclaimer by pointing out that the gas market is insanely complicated. As can be seen with the negative prices at Waha last month, the price of gas varies widely depending on where it’s being produced and whether or not the producer owns (or has purchased) enough pipeline capacity to move their fuel to the market. Prices can also have huge swings depending on the weather and the supply-demand situation in a particular location on any given day.

With that out of the way, here are three reasons natty prices could increase.

Demand is about to surge. There have been scads of bullish calls over the past few weeks. As I explained last month in “The EPA’s Emissions Rules Will Strangle AI In The Crib”:

Tudor Pickering & Holt, a Houston investment banking firm, estimated that AI could require, in its base case, around 2.7 billion cubic feet per day of incremental natural gas. But the figure could also be as high as 8.5 Bcf/d by 2030. In mid-April, an analyst at Morningstar estimated the power burn for AI at 7 to 16 Bcf/d by 2030. Also last month, Rich Kinder, the executive chairman of pipeline giant Kinder Morgan, estimated AI would require 7 to 10 Bcf/d of new gas consumption.

Those are huge increases. Another top energy analytics firm, Enverus, in its fast growth scenario, estimated that gas burn by Big Tech could grow by more than 10 Bcf/d by 2035. Add in exports of LNG which J.P. Morgan estimates could grow by more than 9 Bcf/d by 2030, and it’s clear that gas demand could grow dramatically over the next decade.

LNG exports will be a crucial driver of gas demand. As shown in the graphic above, European and Asian consumers are paying about four times more for their gas than their counterparts here in the U.S. Natural gas bulls believe that those exports will mean domestic gas prices will rise. In a May 31 research note, Goehring and Rozencwajg, a New York-based investing firm, claimed that domestic prices “will converge with the global price.”

Reason number two: shale gas production won’t grow as fast as it has in the past. I will again quote Goehring and Rozencwajg, who believe that after years of soaring growth in gas production:

The shale age appears to be entering the early stages of decline. Production is still growing year-on-year, however the growth has slowed from 10 Bcf/d per year throughout the 2012 to 2020 period to a mere 3.5 Bcf/d presently. Most importantly, on a sequential basis, the dry gas supply likely peaked in December 2023...The US is set to shift from a prolonged period of acute oversupply to a structural deficit of historic proportions. Although inventories remain high, our models predict they will draw to dangerous levels much sooner than anyone believes possible...The current natural gas market represents the perfect storm: dry gas production is faltering just as demand is set to surge. (Emphasis added.)

To be clear, Goehring and Rozencwajg are talking their book. They run the Goehring & Rozencwajg Resources Fund (GRHIX), a mutual fund with big positions in natural gas companies. Their biggest holding is Range Resources. More on Range in a moment.

Third, future wells may not be as productive. As one analyst told me, producers have already drilled their best rock. He said production growth, particularly in the Marcellus Shale, “has plateaued. It’s hard to replicate that earlier growth.” (This EIA graphic appears to confirm that production has flattened in Appalachia.) In addition, the analyst pointed to increasing regulatory constraints, including the EPA’s strict new rules on methane emissions (known as “quad O”), the friction involved in building new pipelines, and the Biden administration’s overt hostility toward all hydrocarbons.

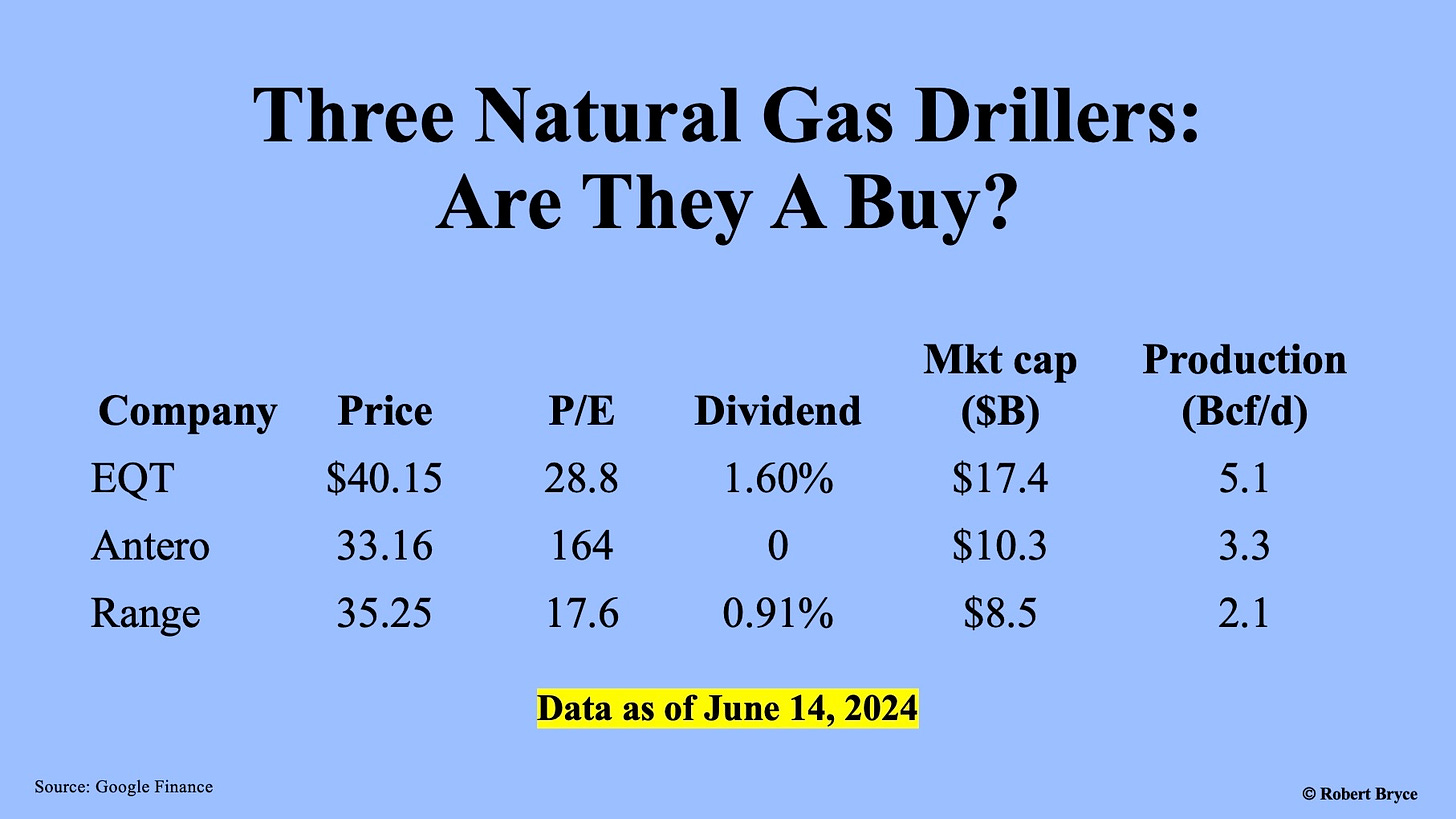

Which companies are most likely to benefit from higher gas prices? The three names I heard the most were EQT, Antero Resources, and Range Resources, all of which get the bulk of their production from the Marcellus Shale. I also heard about Chesapeake Energy, which has a lower P/E ratio and higher dividend than any of these three companies.

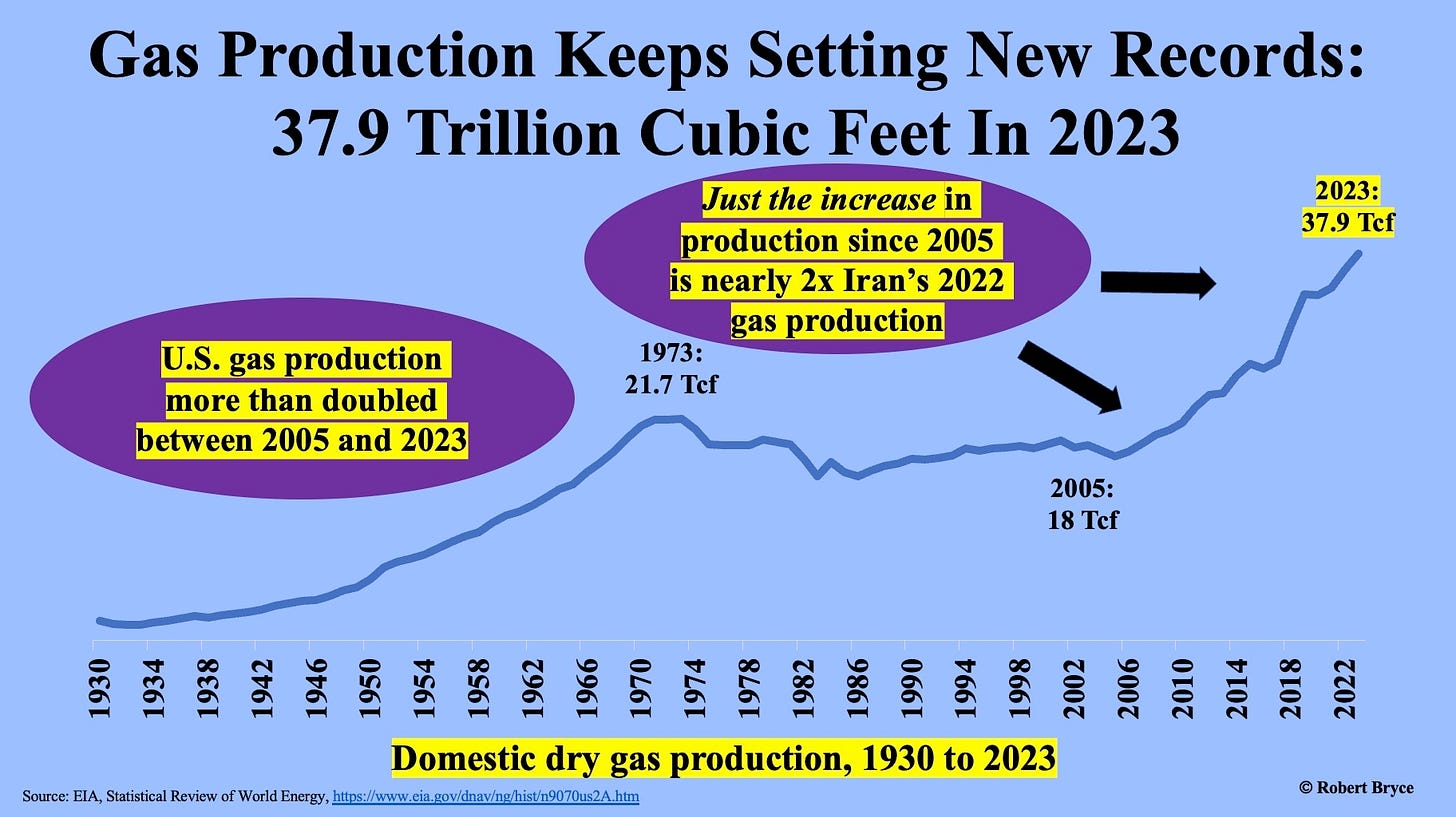

That’s the bullish case. But there are an equal number of reasons to be bearish. As the graphic below shows, U.S. gas production keeps setting new records. Why? The industry keeps getting better at pulling hydrocarbons out of the ground. That point leads to the first reason why gas prices won’t stay high for very long.

Producers are gonna drill. As soon as gas prices increase and stay high for a while, the industry will respond by deploying more rigs. At a recent energy conference in Irving, Texas, Doug Lawler, the president and CEO of Oklahoma City-based Continental Resources, said his company could quickly produce a lot more gas. Lawler said Continental, the biggest privately held oil and gas company in the country, could double its gas production in Oklahoma’s Anadarko Basin to 1 Bcf/d within six to eight months if they wanted to, and they’d only need six drilling rigs to do so.

Shilpa Abbitt, the CEO of Caliber Resource Partners, an Oklahoma City-based energy investment firm, echoed that sentiment. She told me, “The moment prices get higher on a slight demand increase, producers react, and everything corrects again.”

Second, demand could disappoint. As shown in the graphic above, power demand in U.S. has been almost flat since 2005. Yes, we could see a big jump in electricity use, which could mean a big jump in power burn, but we haven’t seen it yet. In fact, overall domestic electricity use fell by 1.7% last year. Furthermore, since 2005, industrial demand has barely budged. Between 2005 and 2023, domestic industrial demand grew by just 1.3%.

Other reasons why gas demand could be less than expected include an economic slowdown here in the U.S. and around the world. In addition, the Biden administration could slap another “pause” on LNG exports, and the expected power burn needed for data centers and AI could be less than everyone expects due to ongoing improvements in computer energy efficiency.

Third, the industry’s ongoing productivity gains are nothing short of astonishing. Last month, I interviewed a longtime oil and gas executive from Tulsa who holds positions in several publicly traded oil and gas producers. When I asked about natural gas, he said flatly, “I’m a doubter of the high prices.” When I mentioned the three gas-focused companies listed above, he replied, “I don’t own any of those stocks.” One of the main reasons he doubts gas prices will stay up for very long is that the industry’s technology keeps improving. “We can drill 24,000-foot wells in 15 days. We do it regularly,” he said

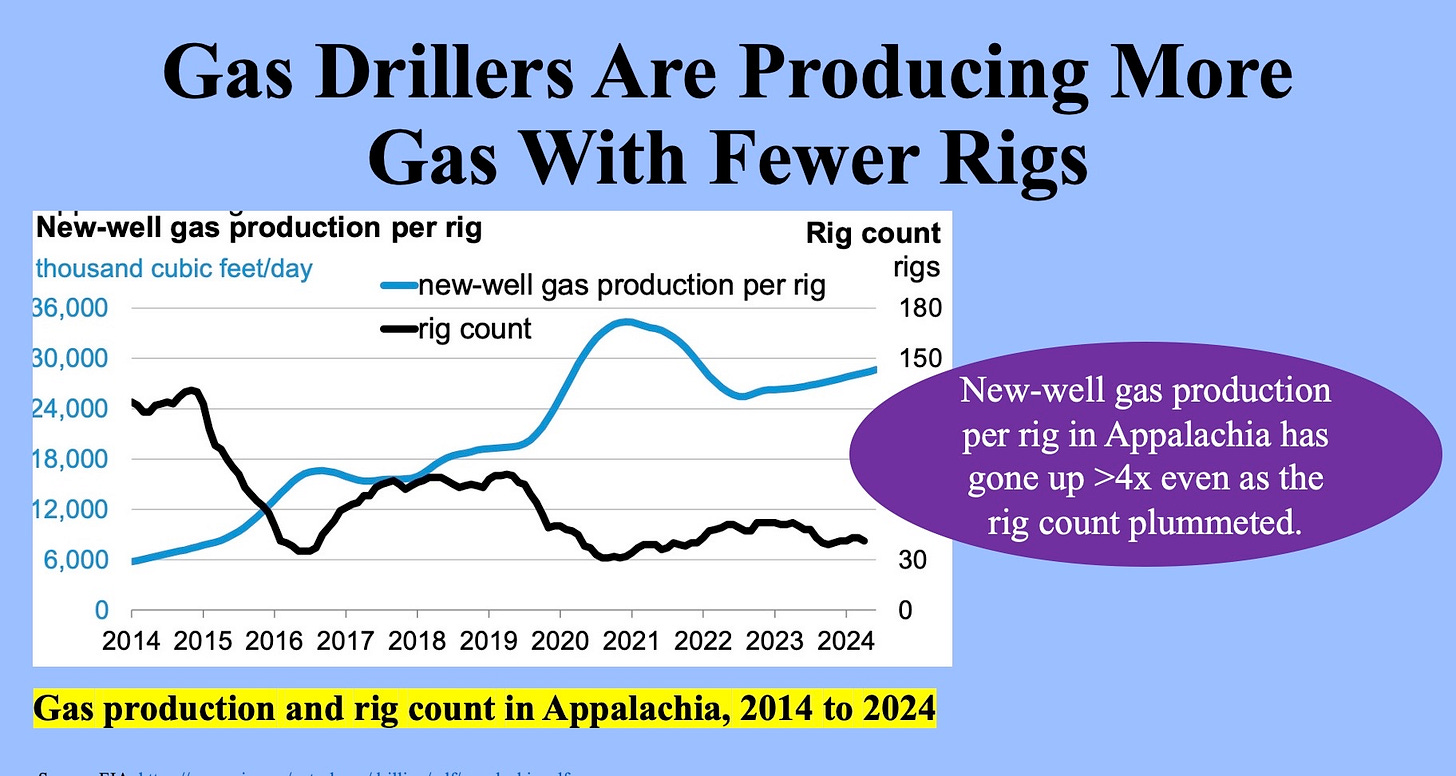

The graphic above, which uses a screengrab from a recent EIA report, illustrates the stunning efficiency increases over the past decade. Between 2014 and 2024, gas production in Appalachia roughly tripled, going from about 13 Bcf/d to about 36 Bcf/d. Over that same period, the number of rigs dropped from about 120 to about 40, and new-well gas production per rig increased from about 6 MMcf/d to about 29 MMcf/d. Those increases are due to better drilling rigs, more powerful pumps, longer laterals (two- and three-mile horizontal sections are now commonplace), and continuing improvements in hydraulic fracturing.

I can see the case for higher prices. But there’s an old adage in the commodities business that has yet to be proven wrong: the cure for high prices is high prices. Place your bets accordingly.

Finally, you might add this side note to your calculations: it appears the Hapgood-Masterson No. 1 is still producing gas.

As always, I’d appreciate it if you clicked that ♡ button.

While you’re at it, please subscribe and share. Thanks.

All this beautiful clean burning natural gas could and should be the savior of residential electricity generation and distribution here in the USA. Smaller high efficiency natural gas power stations utilized in a Shared Modular Grid Configuration will be the future of affordable electricity here and abroad. This approach totally eliminates the need for vulnerable, expensive, expansive grids. Once we the people demand energy freedom from the regulatory NAZIS, pipelines are far less vulnerable and less expensive to develop and maintain. The future is bright ; however, there is a fight to be won. Demand energy freedom for the American people, it’s just common sense. (Thomas Payne). Hugh G.

Capitalism would solve this problem if the government would let it.