An Inflation Hurricane Is Shorting The Electric Grid

Prices for generators, transformers, and other utility components are soaring. Hurricane Helene (and now Milton) will make the problem worse.

The reports about the damage caused by Hurricane Helene and the amount of water dumped on the region by the storm are gobsmacking. Last week, my friend, Jimmy Fortuna, an energy industry executive who lives in Asheville, sent me a text. He said, “Brother, I’m telling you, it’s like God’s own bulldozer went down these mountains and valleys. Maybe it did. Whole sections of town in Asheville and some whole towns in the mountains around us turned into mud flats.”

At least 230 people are confirmed dead from the storm. Major roadways were destroyed and it’s unclear when they will be rebuilt. Last week, a press release from Congressman Chuck Edwards, said some 360 electric substations were “damaged or destroyed” by Helene. And now Duke Energy is warning that about 1 million of its customers should prepare for extended outages due to Hurricane Milton. That Category 5 storm is expected to make landfall on Wednesday near Tampa, Florida.

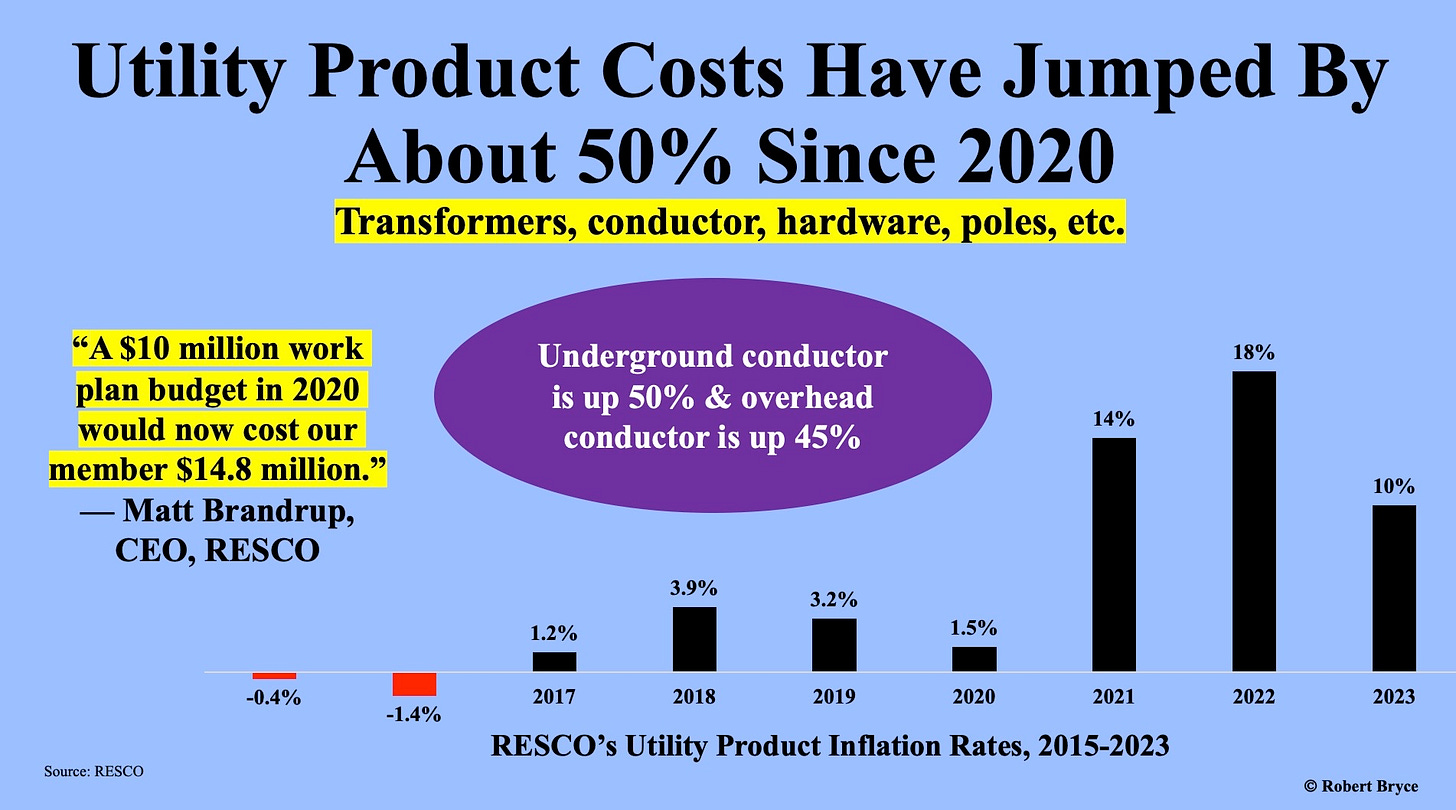

Hurricanes Helene and Milton are shaping up to be two perfect storms that will throw more fuel on the inflation storm that’s slamming the US electric grid. At the exact moment US utilities are facing EPA mandates to decarbonize their generation mix and the Biden Administration is pushing for massive expansions of high-voltage transmission and alt-energy capacity, the prices for all types of utility kit — from breakers and transformers to hardware and gas turbines — are soaring.

These hurricanes will put additional pressure on utility supply chains that are already struggling to keep up with demand. Add in shortages of skilled labor, and the result is that prices for critical components — and even whole power plants — have jumped by as much as 75% in less than two years. And those soaring prices will, of course, ultimately be paid by consumers.

Over the past few months, I’ve interviewed several dozen people who work in the power sector about the supply chain and labor challenges they face. The best summary I got was from an engineer who works at a leading engineering, procurement, and construction firm. He told me “If we had the parts, we don’t have enough people. And if we had enough people, we don’t have the parts.” Indeed, an inflationary hurricane is shorting the grid. (A hat tip here to my pal, Meredith Angwin, and her marvelous book, Shorting The Grid.)

Here's what I have found in my reporting over the past few months, along with five charts that illustrate the inflation now hitting the US electric grid.

Let’s start with labor. Over the past six months, at multiple conferences, I’ve heard that the shortage of skilled labor is, in many cases, acute. In July, during a conference sponsored by the Virginia Manufacturers Association, one of the speakers addressed the challenge of trying to build more data centers in the state. He said, “We don’t need any more engineers. We have engineers. We need more welders, electricians, and pipefitters.”

Last month, I talked with the engineer from the EPC firm I mentioned above. He said his firm is turning down work because they don’t have enough skilled labor to do it. “We don’t have the materials and we are racing toward not having the people...We are paying non-union laborers union-scale wages.” In addition, he said the skill level of the workers his company employs has declined. That means he has to deploy twice as many on-site supervisors as he did a few years ago. The higher labor and material costs have resulted in eye-popping increases in project costs. About 20 months ago, his firm estimated the price of a large gas-fired power plant at $400 million -- and that price did not include the gas turbines. “We just turned in a firm price of $700 million,” he told me.

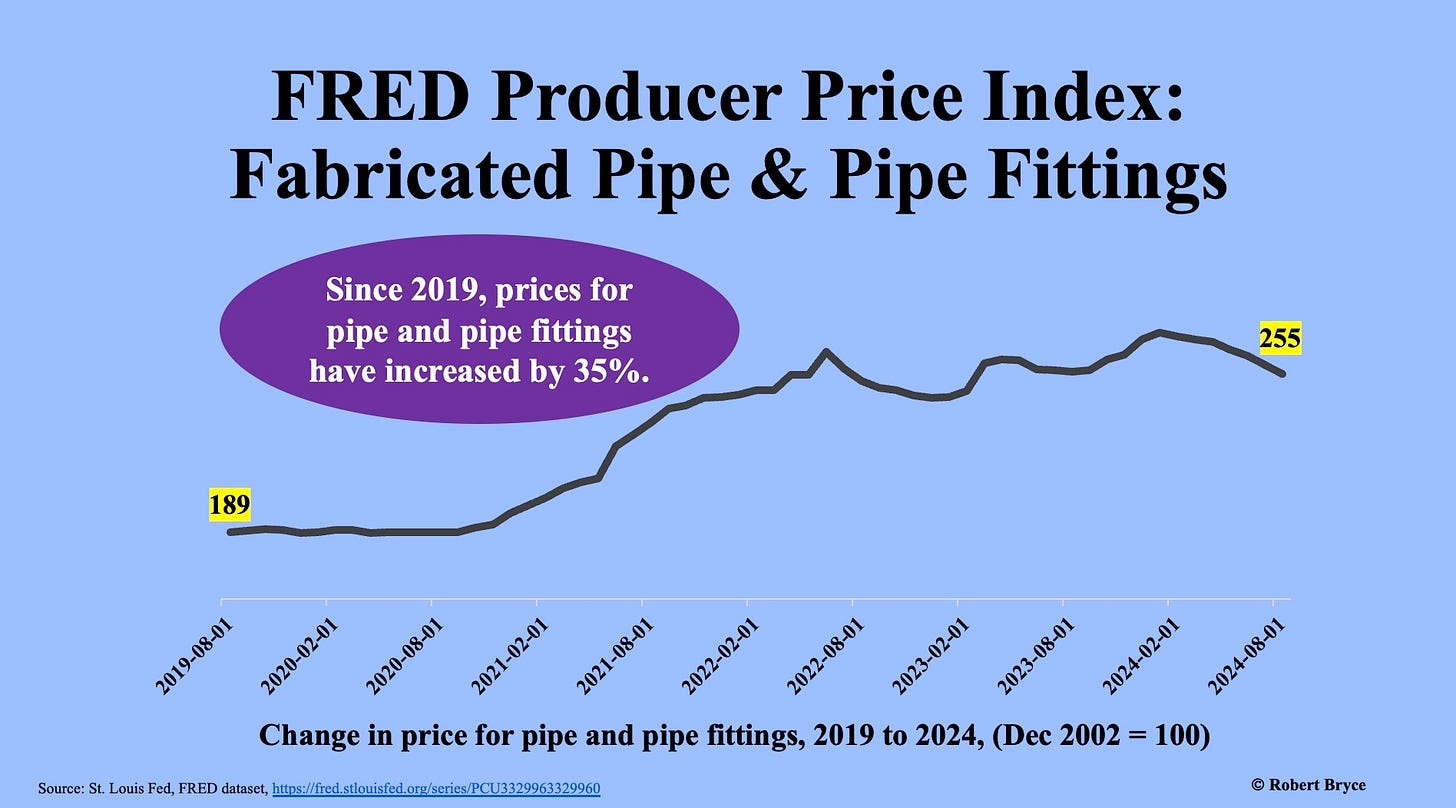

In addition to the 75% increase in project cost in less than two years, the same engineer told me that the critical high-voltage equipment, including breakers, transformers, and switchgear, are all long lead-time items. “They drive all of our schedules.” He also said that even pedestrian commodities, including pipe and pipe fittings, are soaring in price.

As seen above, data from the St. Louis Fed shows that the prices for pipe and pipe fittings have jumped by 35% since 2019.

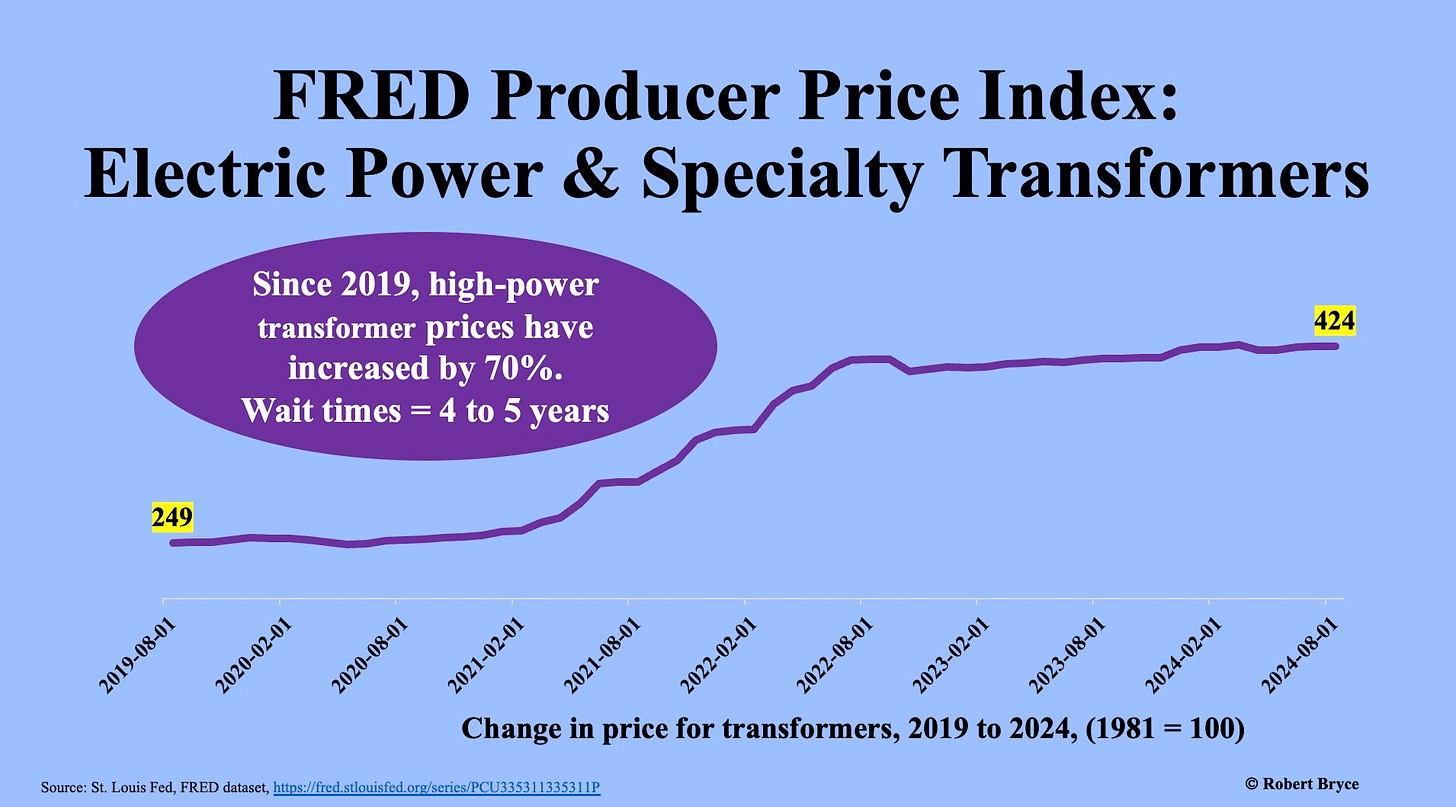

The St. Louis Fed data also show huge increases in transformer prices. But price isn’t the only hurdle facing the electric sector. The other challenge is availability of key components. Several sources in the industry pointed out that the domestic electric sector must now compete in the international market for items like gas turbines, breakers, and transformers. For example, they pointed to a $7.8 billion deal announced last year by Saudi Arabia, which is rapidly expanding its electric grid. The agreement calls for the construction of some 7,200 megawatts of new gas-fired capacity in the kingdom. In June, Siemens Energy and GE Vernova announced that they were supplying turbines with a total capacity of about 3,800 megawatts to the kingdom.

“It’s a different ballgame,” an executive at a large equipment manufacturer told me. “It’s much more of a global market with major global demand. We’ve seen global demand before, but nothing like the Saudis saying, ‘We need 8 gigawatts.’” He continued, saying that demand “Has strained the supply chain... you are trying to supply multiple markets that have huge needs.”

How bad is the situation? The executive told me his firm, which manufactures large gas turbines (170 megawatts and above) known as frame, or F-class machines, now has a waitlist of four years. In addition to the long wait times, the price tag for those turbines has increased by 50 to 75% over the past two to three years.

The same firm also makes high-power transformers. “The transformer situation is as bad or worse than gas turbines,” he told me. “It’s four to five years for large transformers.” When I asked about the voltages, he said all the transformers have extended lead times. “Once you get to 230 kV, the lead times increase with the voltage. All of them have super-long lead times. Four to five years,” he said.

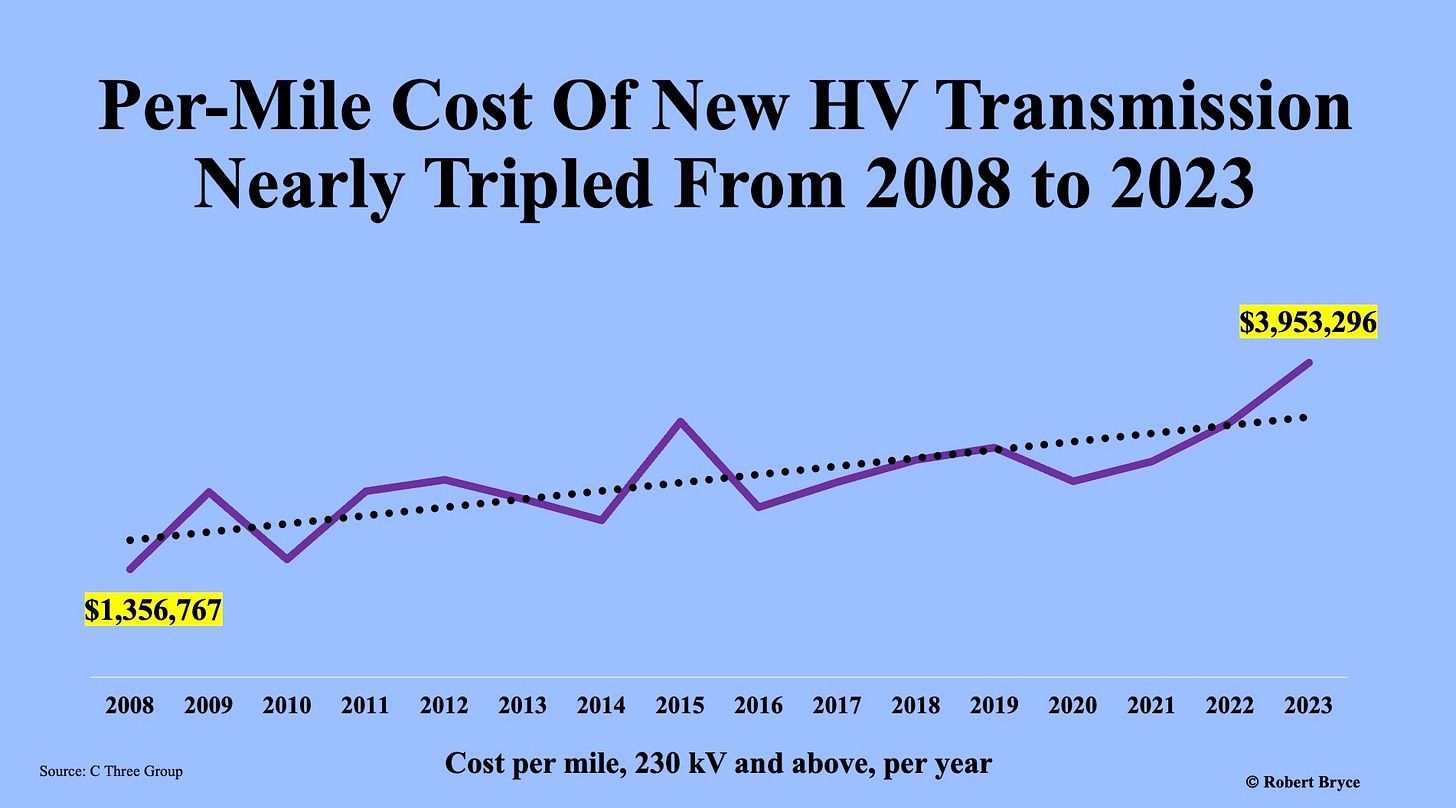

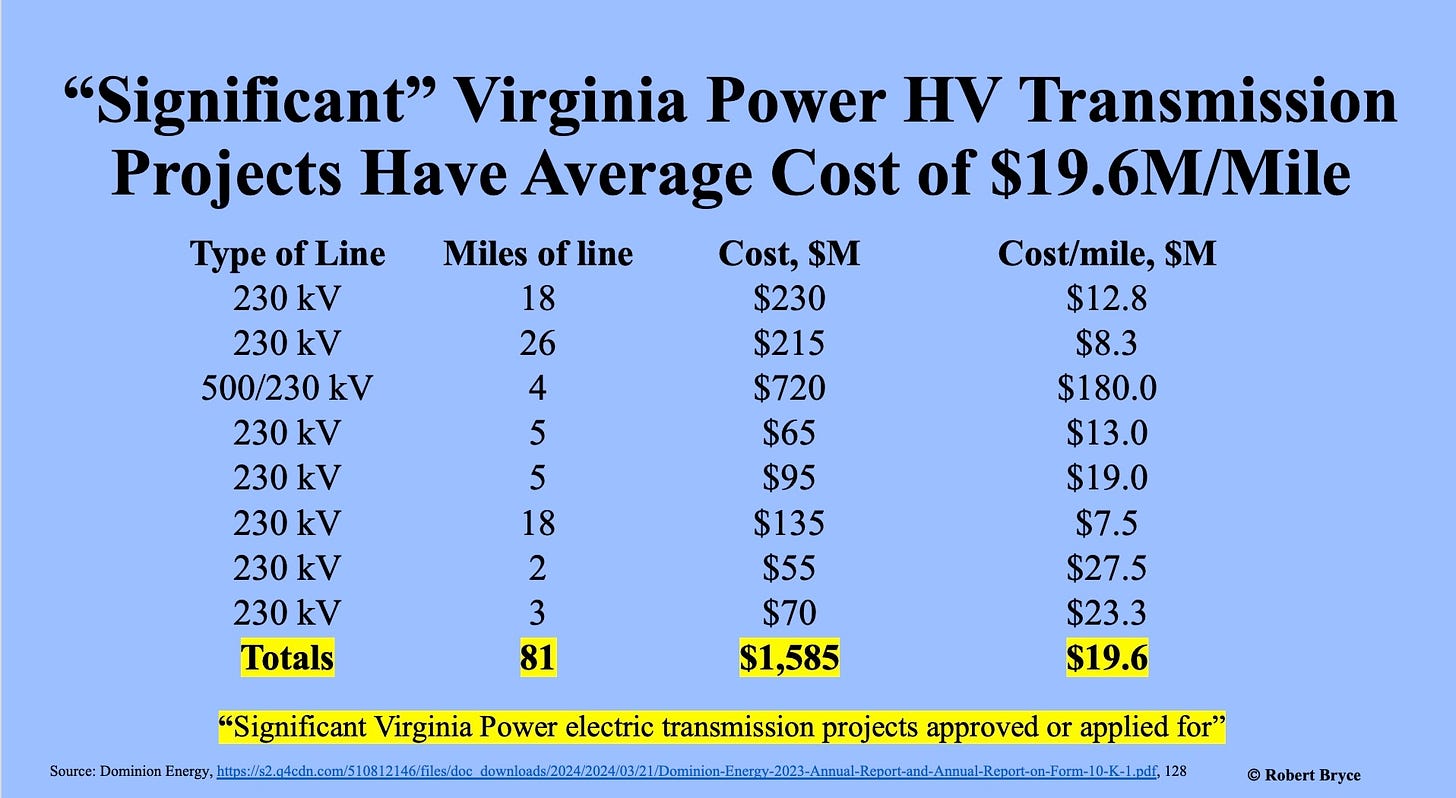

The cost of high-voltage transmission capacity is also soaring. According to data from C Three Group, the per-mile cost of new capacity has nearly tripled since 2008. Costs show no sign of slowing. The costs on some projects boggle the mind. Dominion Energy noted in its 2023 annual report that it is working on a project in Loudoun County, Virginia, that includes new substations and four miles of high-voltage transmission. The estimated project cost is $720 million, or about $180 million per mile. The utility also published a list of other “significant” Virginia Power transmission projects.

As seen above, the company is now building about 81 miles of transmission projects that will cost nearly $1.6 billion, or about $19.6 million per mile. Even if we remove the Loudoun County project from the list, the cost of the new transmission still exceeds $11 million per mile. Of course, consumers will ultimately pay all of those costs.

The takeaway here is obvious. While academics, politicians, NGOs, and climate activists are claiming we need to electrify everything due to concerns about catastrophic climate change, the people who are replacing aging grid infrastructure, hardening the existing grid, building new power plants, repairing hurricane-damaged equipment, and preparing the electric sector for big increases in demand from AI, EVs, and other electron-hungry gear, are saying that they don’t have the parts, or the people, to get the job done.

In other words, the energy transition we keep hearing about will not happen quickly, will not be easy, and will definitely not be cheap.

Before you go:

Please do me a favor by clicking that ♡ button. And, of course, please share and subscribe.

Sadly very little of this madness is necessary. We are wasting resources to connect worthless wind and solar resources we don’t need, that are hundreds of miles from load centers, all because some bought, corrupt, manipulated computer models say the temperature might go up at some point in the future.

All this new transmission is pure fallacy. Early in my career an old engineer told me it is easier to move molecules than electrons. In 50 years I have never seen a case where that isn’t true.

Thank you Robert. I am frequently reminded, so endlessly quote, a saying an esteemed former boss of mine had in a frame on his office wall: "Nothing is impossible for those who don't have to do it".