Frank Sprague: America’s Greatest, Least-Known Inventor

Sprague perfected the electric motor, electric streetcar, and electric elevator. In doing so, he changed the world. But he’s almost unknown among American inventors.

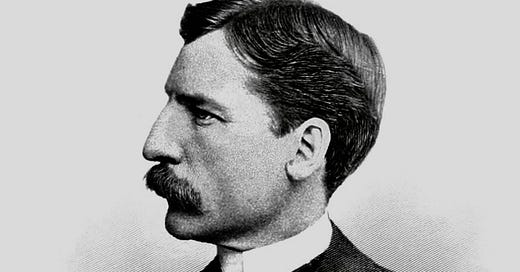

The pantheon of great American innovators includes people like Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Graham Bell, Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, the Wright Brothers, Eli Whitney, and Steve Jobs. But historians and technologists have largely overlooked Frank Sprague. Orphaned at the age of eight, Sprague would go on to attend the Naval Academy, work briefly for Edison, and become a titan of the Electric Age. During his long career, he was issued 95 patents for innovations in railway machinery, pumps, electric circuits, and electric motors. In 2020, I published my sixth book, A Question of Power: Electricity and the Wealth of Nations, which includes a chapter on Sprague called “The Vertical City.” I’m reprinting that chapter here. While writing A Question of Power, I also produced a feature-length documentary with director Tyson Culver. That film, Juice: How Electricity Explains The World, features a long look at Sprague and explains how, by perfecting the electric elevator, he fueled the rise of the vertical city. As you will see below, I’ve inserted excerpts from our documentary, which was released in 2019. (You may watch the entire film for free on YouTube).

I’m publishing this chapter and these interviews with the hope that more people will appreciate the innovations and breakthrough technologies pioneered by Frank Sprague, America’s greatest, least-known inventor.

The Vertical City

In 1882, when Thomas Edison launched the Electric Age with the first commercial electric grid, New York City was squat and squalid. The tallest structures in the city were the towers of the Brooklyn Bridge, which stood 84 meters (276 feet) high. The great bridge, designed by John Roebling had been under construction for 13 years was finally nearing completion. Edison and his employees, were likely closely monitoring the work on the bridge as it was just a few blocks east of Edison’s generating station on Pearl Street.

New York’s streets, as usual, reeked of horse feces and urine. Horses and horse-drawn wagons and streetcars dominated the thoroughfares. The air was often fouled with smoke from the many coal-fired steam engines that were providing power to factories, print shops, and other industries. Inside the city’s homes, offices, and factories, gas lighting – with all the heat and noxious fumes that came with it – dominated. For exterior lighting, entrepreneurs like Charles Brush had used arc lights to illuminate sections of the city.

The tallest building in the city was the Equitable Life Assurance Building at 120 Broadway. Located about half a mile west of Edison’s power plant, the Equitable building stood 40 meters (130 feet) high and was nearly twice the height of all previous business buildings. Completed in 1870, it was billed as a fire-proof building. It was constructed with iron framing and had ten floors that were served by five steam-powered elevators. Tourists flocked to the building to ride the elevators and visit the rooftop observation deck which also served as the site of New York City’s weather bureau. New Yorkers marveled at the Equitable building because nearly all of them lived and worked in buildings that were only half as tall, if that.

For nearly all of human civilization, the height of buildings was limited by people’s willingness to climb stairs. Any building taller than four, five or six stories, was impractical. Walking up two or three flights of stairs isn’t terrible. Carrying a load of groceries and a screaming infant up three or four flights of steep, dark stairs, is, pardon the pun, another story.

By electrifying part of Lower Manhattan, Edison ignited the rise of the vertical city. Indeed, the Electric Age and the skyscraper were birthed at about the same time and that birthing occurred in a remarkably small region of Lower Manhattan that covers about one square mile. There, Edison, Nikola Tesla, and George Westinghouse converged to pioneer the shape and components of the modern electric grid. But a lesser-known inventor — a man, who, like Tesla, briefly worked for Edison — was to leave an indelible mark on the urban environment. His name was Frank Julian Sprague.

Sprague doesn’t have the name recognition of Tesla, the Serbian-born genius who invented the AC motor. Nor is Sprague’s name as famous as that of Westinghouse, the industrialist who commercialized the transformer, the device that allows electricity producers to boost (or decrease) the voltage carried on a given electricity line. Tesla, Westinghouse and Edison get plenty of well-deserved attention. But it was Sprague who developed the first electric motors that ran on Edison’s grid. Sprague would go on to electrify urban transportation by putting his motors on streetcars, subways, and railroads. But it was at 253 Broadway, just half a mile northwest of Edison’s original power plant on Pearl Street that Sprague deployed the first set of electric elevators, a technology that would fundamentally reshape our cities.

Born on July 25, 1857 in Milford, Connecticut, Frank Julian Sprague knew hardship from an early age. His mother died when he was eight years old. A few months after her death, Frank and his brother, Charles, were abandoned by their father. They were taken in by their aunt, Elvira Betsy Ann Sprague, who lived in North Adams, Massachusetts. In 1874, Frank was encouraged to take the entrance exam for West Point, but instead ended up taking the entrance test for the US Naval Academy. Sprague did well and was admitted to the school in Annapolis. The Naval Academy, which was then considered one of the best universities in the country, was perfect for Sprague. Midshipmen were schooled in everything from navigation to geometry. As one Sprague biographer put it, at the Naval Academy, students were “taught to think concretely, abstractly, and above all, systematically.” Those skills would be critical to Sprague’s success. He graduated in 1878, ranking seventh out of his class of 50, earning honors in math, physics, and chemistry. He later recalled that while in Annapolis, he “developed something of a flair for mathematics, and particularly for naval architecture and physics.”

Sprague took an early discharge from the Navy to work for Edison. His first day working for the great inventor was the same day the Brooklyn Bridge opened: May 24, 1883. Edison immediately put Sprague to work overseeing the installation of new electric grids in Sunbury, Pennsylvania and Brockton, Massachusetts. Sprague proved his worth almost from the outset, showing Edison’s men how to use mathematical calculations to determine the size of wiring needed to serve the demand on a given electric grid.

Sprague’s technical training and mathematical skills stood in sharp contrast to Edison’s method of endless experimentation. Sprague was impressed by Edison’s operation, but he wasn’t happy. He wanted to develop and deploy electric motors for industry and transportation. Joseph J. Cunningham, the pre-eminent historian on the electrification of New York City and the author of the excellent 2013 book, New York Power, told me that “the value of a practical motor had become obvious to Sprague” while he was working for Edison. But Edison showed no interest in developing a motor and instead focused on lighting.

In April 1884, after just 11 months with Edison, Sprague set out on his own, a move that he admitted later, came with “considerable risk.” That’s an understatement. When he quit Edison, Sprague was 27 years old, new to New York City and had little money. His salary with Edison had been modest: $2,500 per year (about $65,300 in 2016 dollars). Quitting the most famous and successful inventor of the 19th century was one of many risky bets that Sprague would make over the next two decades.

Sprague may have frequently lacked the money needed to commercialize his inventions, but he never lacked for confidence in his ability and intellect. Prior to Sprague, electric motors were largely theoretical. Edison and others had fashioned motors out of generators by running them backwards, that is, rather than spinning the rotor on the generator to produce outgoing current, they would feed electric current into the generator. Edison thrilled visitors to his laboratory in Menlo Park by giving them rides on a miniature train that he had built on the grounds. The track was about a mile long and provided power to the train through electrified rails. The train could reach speeds of 40 miles per hour but it didn’t have a proper motor, instead, it used a generator that was running in reverse. Although such an arrangement could work, it forced the generator to perform at a task for which it hadn’t been designed.

Sprague saw an opportunity. His confidence attracted investors, the most important of whom was Edward Hibberd Johnson, who was also one of Edison’s early backers. With Johnson’s backing, Sprague set up his own shop and began designing and building direct-current (DC) electric motors. Within a few months, he had several working prototypes which he showed at the Philadelphia Electrical Exposition in September 1884.

This is an excerpt of an interview we did with Joe Cunningham that appeared in Juice: How Electricity Explains The World.

As Cunningham explains, Sprague’s motors “took industry by storm.”1 They were powerful, compact, and operated at constant speed with little or no sparking. Edison himself endorsed Sprague’s motor, calling it “the only true motor; the others are but dynamos turned into motors. His machine keeps the same rate of speed all the time, and does not vary with the amount of work done.” For a time, Sprague’s motors were the only ones allowed to run on Edison’s New York grid. Textile producers and other manufacturers were among the eager customers for Sprague’s new motors. Within a year of launching his new venture, Sprague had sold 3,000 of them. Within a decade, 47 different types of electric motors produced by Sprague and other companies, had “found application on cranes, lifts, machine tools, and other equipment.”

While his motors were an immediate success, Sprague wasn’t satisfied with putting them into cranes, lifts, and looms. He wanted to electrify transportation. There were plenty of reasons for that. By the 1880s, New York and other bustling cities were desperate to find an alternative to horse-drawn trolleys. Some 40 horses per day were dying on the streets of New York City, victims of accidents, overwork, or broken legs from slipping on slick cobblestone streets. The average life expectancy for a horse pulling a streetcar was less than two years. Those herds of horses were depositing hundreds of tons of manure and tens of thousands of gallons of urine per day on the city’s streets. Vacant lots were piled high with enormous mounds of stinking dung. The manure provided a breeding ground for swarms of disease-carrying flies, which were blamed for outbreaks of typhoid and other health problems. During dry periods, the manure was a stinky nuisance that mixed with the city’s airborne dust. During heavy rains, the dung merged with water and mud to form a slimy, pungent, pollutant that stuck to everything it touched.

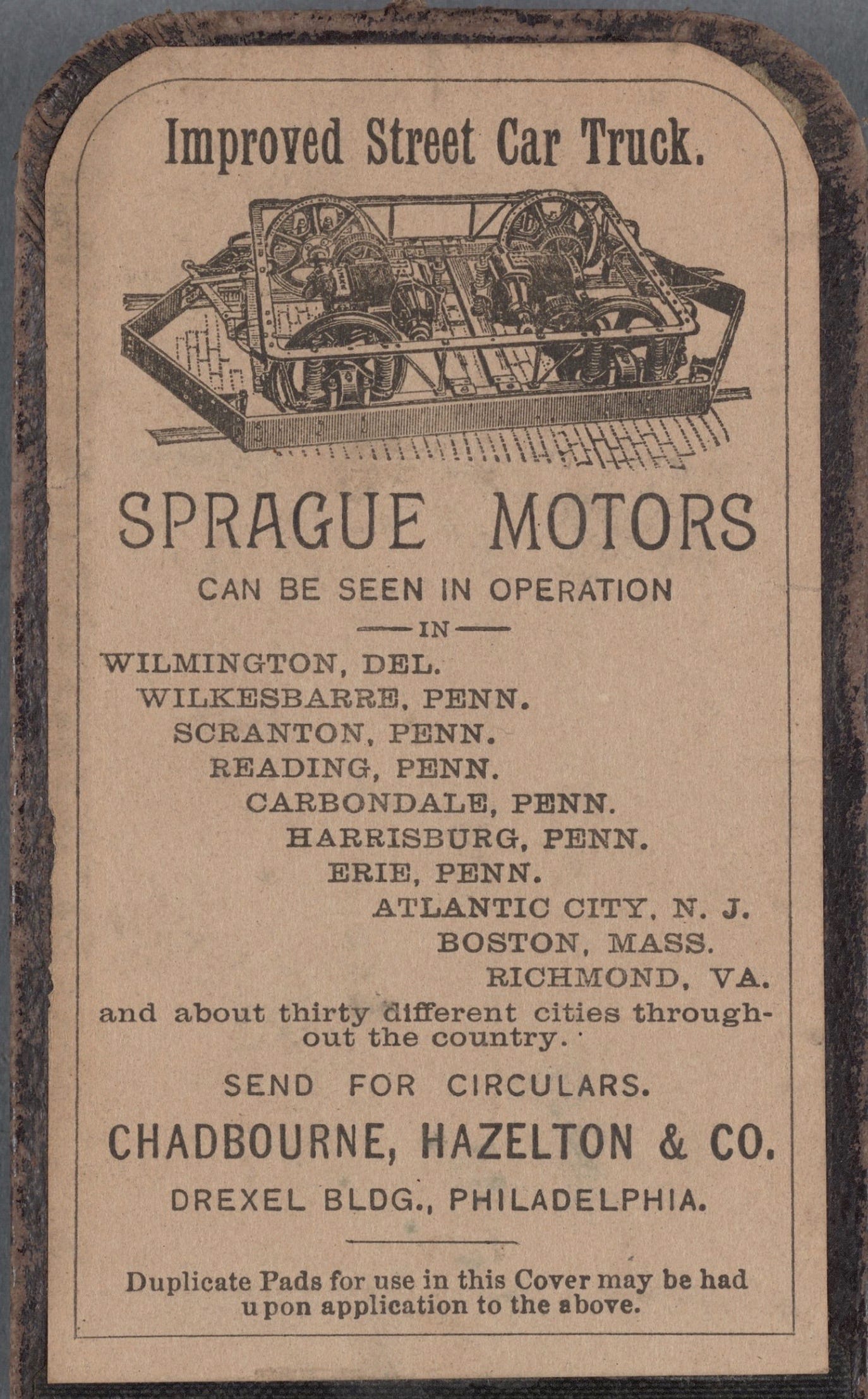

Sprague knew that his electric motor could provide a faster, cheaper, cleaner method of urban transport. In November 1884, just two months after showing his motors in Philadelphia, Sprague and Johnson formed the Sprague Electric Railway and Motor Company. Over the next few months, he had, in his words, “schemed out” plans for an electric railway and began testing a prototype in New York City. Sprague hoped his first customer would be the Manhattan Elevated Railway which was owned by the financier Jay Gould, who was one of the richest people in America. He was also one of the most reviled. (In 1869, Gould and another financier, Jim Fisk, tried to corner the gold market. They failed to do so, but their attempt caused the prices of stocks and agricultural products to plummet.) Gould owned a controlling interest in the Manhattan Elevated Railway Company, which ran the Second, Third, Sixth, and Ninth Avenue elevated lines, all of which used steam-powered locomotives. The steam locomotives provided transportation to city residents, but they were hated by New Yorkers because they were dirty and noisy. And because they were elevated, they often showered sparks and coal dust onto pedestrians below.

Sprague got an opportunity to demonstrate his technology for Gould. But the demonstration ended badly after Sprague — who was operating one of his prototype rail cars — suddenly reversed the current in the controller, which caused a loud explosion and a load of flying sparks. Gould, startled by the explosion, tried to jump off the train and left in a huff. Unable to prove his technology in New York, Sprague signed a contract in May 1887 to install an electric rail system in Richmond, Virginia. The risk of the deal was obvious. The deal called for the Richmond Union Passenger Railway to pay Sprague $110,000 (about $3 million in 2016 dollars) but only once the entire system – 40 cars, 80 motors, and a central station generating 280,000 watts (375 horsepower) – were operating satisfactorily. Thus, Sprague was going to have to construct a power plant that was about half the size of Edison’s first generating station on Pearl Street (which was rated at 600,000 watts) and he was going to have to do something far more complicated than what Edison had achieved.

Sprague’s grid would have to do more than merely provide illumination. Sprague had to build a grid that could power heavy, moving cars loaded with dozens of people. He would have to engineer a motor strong enough and durable enough to handle highly variable loads. He also had to figure out how to mount the motors on the carriages and design a system that would supply continuous power to the moving cars. Moreover, he had to prove that it could all be done safely, cheaply, and under a crushing deadline. Sprague later admitted that the contract for the Richmond system was one that a “prudent businessman would not ordinarily assume.” If he failed to make the rail system work it would mean “blasted hopes and financial ruin.”

When he started, Sprague had only a blueprint of the Richmond system. He had to design, test, and deploy everything that would be needed, from the overhead wire system to how to attach his motors to the axles of the cars. Making matters worse, Richmond was a terrible place to test his system. As author Frank Rowsome explains in his marvelous 2013 biography of Sprague, The Birth of Electric Traction, the streets of Richmond would challenge the great inventor at every step. Shortly after the project got underway, “serious problems emerged. The steep grades and sharp turns of Richmond’s topography, its unpaved streets, and its clay soil rendered the route a ‘horse killer’ that was ruinously expensive to operate by traditional technologies.”

But Sprague had a genius for machines and the tools needed to build and repair them. As Rowsome put it, Sprague “was a man for whom machinery wanted to work…he had an instinct for elegant simplicity in design and for arrangements of mechanism that could be persuaded to work without endless finagling.” Despite his genius and his equally significant aptitude for hard work, Sprague and his team endured myriad setbacks, including derailments and burned out motors. The setbacks were costly and forced Sprague to miss a deadline. The owners of the railway demanded, and got, a reduction in the final price, to $92,000. But Sprague and his team of engineers and mechanics pressed on and in May 1888, just 12 months after he signed the contract, the Richmond Union Passenger Railway was declared a success. Sprague’s rail cars were traveling a total of 11,000 miles and carrying some 40,000 passengers per week. The owners of the railway were ecstatic. By the time they paid Sprague, the new railway was producing profits of about $6,000 per month.

By completing the system in Richmond, Sprague had designed, built, and successfully deployed, the world’s first full-scale commercial electric railway. His success in Richmond helped fuel the deployment of similar systems all over the world. Not only that, the designs that Sprague developed for the Richmond system — including the way he attached his motors to the axles and truck frames of the railcars — would become the standard design for electric trolley and rail systems around the world.

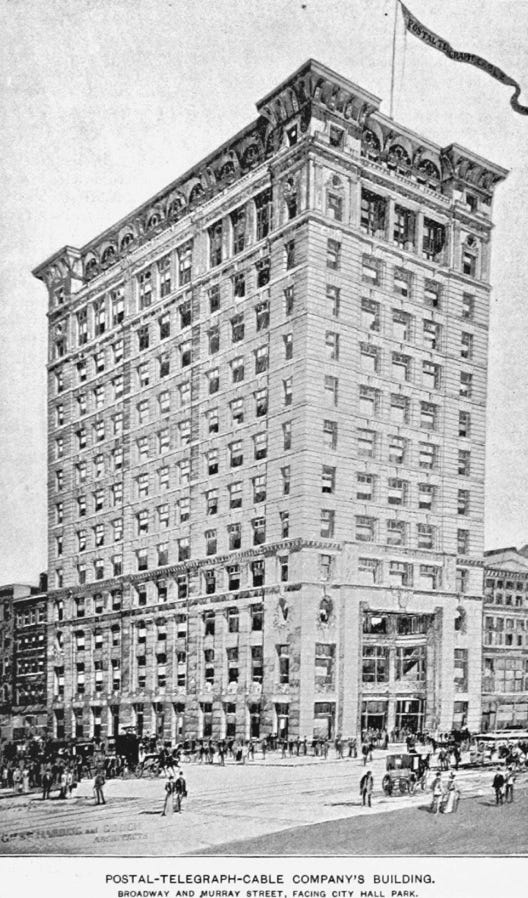

After figuring out how to use his electric motors to move passengers across the horizon, Sprague focused on moving them skyward. In 1891, he formed the Sprague Electric Elevator Company with a partner, Charles Pratt, who owned patents on a couple of elevator technologies that overlapped with Sprague’s designs. The new venture got its first opportunity when the Postal Telegraph Cable Company decided to build a skyscraper in lower Manhattan at 253 Broadway. Formed in 1883, Postal Telegraph was among the fastest-growing companies of that era and quickly became a key competitor of Western Union, which was controlled by Jay Gould. The new building was to signify that the Postal Telegraph company could compete with Western Union. The new building was to be among the tallest in New York. Due to the prestige that would inevitably come with such a project, the competition for the elevator contract was fierce. At that time, Elisha Otis’s elevator company dominated the market with its hydraulic elevators. But the contract was nevertheless won by the Sprague Electric Elevator Company.

The deal required Sprague’s new company to install six elevators: two of them were to be express elevators. The remaining four would provide local service. The contract called for Sprague’s electric elevators to equal, or exceed, the speed of hydraulic elevators. In addition, they were to require less maintenance and use less space. As with the Richmond railway contract the deal was dangerously one-sided. If his elevators didn’t work as Sprague promised, the contract required him to rip them out and replace them, at his cost, with hydraulic elevators. Thus, Sprague had to – from scratch – design, test, and install everything he was going to need. If he failed, it meant buying a complete — and in his view, inferior — elevator system from his rivals. Nevertheless, on October 8, 1892, Sprague signed the contract to install electric elevators in the Postal Telegraph building.

Over the next two years, Sprague and his team overcame a myriad of problems. Among the most difficult to resolve was making the elevator cars run smoothly, without sudden jerks or starts. Passengers on horse-drawn street cars were used to being aboard a vehicle that stopped or started suddenly. Passengers knew to hold tight to the carriage in case a horse slipped, or started up suddenly. They hung on instinctively because they didn’t want to be tossed overboard. Furthermore, passengers on street cars could anticipate bumps, or sudden starts by watching the traffic around the street car and the horses pulling it. By contrast, elevator passengers have no way to anticipate what might happen. There are no horses or traffic to monitor for visual or audible clues.

Through patient testing and development, Sprague solved the problem of jerky starts and stops. He also made other key refinements to vertical transportation, including an automatic floor-alignment system and a self-centering operator’s control that stopped the elevator car if it was released, a mechanism that became known as the “dead-man’s control.” By 1894, when the Postal Telegraph Building was finished, Sprague’s elevators worked perfectly. Sprague received a letter from the architects which praised his machinery saying that even though the electric-drive system was “a radical departure in elevator practice,” the new elevators, in “economy of space occupied, speed, ease of motion, safety, and cost of running, the building committee as well as ourselves, are decided of the opinion that the results have far exceeded our expectations.”

Another remarkable fact about Sprague’s first set of elevators at the Postal Telegraph Building is this: they operated at speeds comparable to those of modern-day elevators. Four of the elevators Sprague installed at the Postal Telegraph building operated at a speed of 325 feet per minute (5.9 kilometers per hour). That’s the speed of a brisk walk. The two express elevators whisked passengers skyward even faster: at 400 feet per minute, or 7.3 kilometers per hour.

This is an excerpt of an interview we did with Carol Willis of the Skyscraper Museum that’s included in Juice: How Electricity Explains The World.

That speed was key to their success. Elevators have to be fast. In cities, and in small towns, we want to travel as fast – or faster – when we travel vertically as we do while traveling horizontally. People in cities are in a hurry. A New York minute doesn’t last very long because residents of Manhattan, Brooklyn, and the other three boroughs have places to go and people to see.

Our travel habits are determined not necessarily by distance, but by time. That is, we don’t worry so much about how far we need to travel, as we do about how long it will take us to get where we’re going. This time budget has become known as the Marchetti Constant. Named for the Italian physicist Cesare Marchetti, it says that people spend about an hour per day getting around — going to work, shopping, and going to school. Further, Marchetti found that that hour-per-day rule applied to ancient cities such as Rome and Marrakesh. Those cities were about five kilometers across, which was about the distance an average person can walk in an hour. To prove his point, Marchetti compared the geographic growth of Berlin over time and found that it expanded concentrically over the years as advances in transportation increased the distances people could travel during that one-hour time period.

Our travel-time constraints also apply to vertical transportation. With the electric elevators at 253 Broadway, Sprague proved that vertical transportation could be just as fast – and far safer – than traveling by foot on level ground. That was a crucial turning point for New York’s real estate market. Sprague’s elevators helped make the vertical spaces above the streets as valuable – or more valuable – than what lay along the bustling boulevards. Today, the world’s most-prosperous cities are routinely populated by office and residential buildings that are 50 stories tall and taller because occupants and visitors can get from the street level to the penthouse in a minute or two.

“Electricity is why we have modern cities,” says Jesse Ausubel, the director of the Program for the Human Environment at Rockefeller University in New York City. Electrification “completely transformed the structure, the geography the geometry of cities.”

This is an excerpt of an interview we did with Rockefeller University’s Jesse Ausubel that’s featured in Juice: How Electricity Explains The World.

Ausubel went on, “Rome, 2,000 years ago, had a million people. But essentially cities remained the same for hundreds, thousands of years.” The limit of all the old great cities, “whether it was Beijing or Baghdad or Rome or Cairo…,” was about 1 million people. After electrification, he said, “suddenly we were able to move into three dimensions.” With electricity, we can “have these cities not just of one million, but of two, and three, and five, and ten million people.” Ausubel continued, saying “basically, height is electrical.” In other words, the taller the building, the more restricted we are in the types of energy that can be used. In a one-story building, Ausubel said, “it's not much of a problem to bring some hay, or a cord of wood, or whatever, to create heat or other forms of energy. However, if you have a 10-story building, wood and hay don't work very well. If you have a 100-story building, the only kinds of energy that you want in a very tall building like that in fact are electricity and gasses.”

The electrification that began in New York City shaped cities. It also shaped the natural environment. Tall buildings fueled by electricity allow cities to have greater population density. Those densely packed vertical cities help reduce the human footprint on the natural world. “Cities are the salvation of nature,” Ausubel told me, “It’s only by concentrating a significant portion of humanity in livable, attractive cities, that we have the chance to spare the rest of nature for the lions, and the tigers, and the eagles.”

The impact of electrification on New York City and its population can be seen in the numbers. In 1880, two years before Edison launched the Pearl Street plant, the city held 1.2 million people. Two decades later, the population had nearly tripled to 3.4 million. By 1930, the population had doubled again to 6.9 million. Electricity unleashed the beast of what New York City is today. It allows 8.6 million people to thrive in one of the world’s densest and most vibrant cities.

Today, the world’s cities contain more than half of the world’s population but cover less than three percent of its land. Those small footprints are obvious in New York City. People who live in the Big Apple use less energy and less stuff than their counterparts in suburban America because they live in smaller spaces, many of which are stacked on top of each other. It takes far less cement, wood, and copper to provide living space for an apartment dweller in mid-town Manhattan than it does to house a suburbanite living in Sugar Land, Texas.

By pioneering electric elevators and electric transportation, Sprague not only helped spare nature, he also had a hand in creating an urban real-estate boom. Some of the world’s most-expensive real estate can be found atop the tallest buildings. In 2014, the penthouse at the Odeon Tower in Monaco, a 170-meter (560 feet) skyscraper, was put on the market for $400 million. In Singapore, the “super penthouse” in Clermont Residences, the tallest residential structure in the city, was available for a mere $47 million. About that same time, a penthouse pad at the Pierre Hotel in New York was selling for $125 million and three other high-rise apartments in Manhattan were selling for about $100 million.

Those swanky apartments are only part of the real-estate story. In 2017, a group of economists estimated that the land in New York City — repeat, just the land, not the buildings — was worth about $2.5 trillion. That land is worth trillions because of what can be built on it, or rather, what can be built above it. Electrification allowed New York to become one of the world’s most-vertical cities.Only Hong Kong has more skyscrapers — which currently refers to buildings that are at least 150 meters (which is roughly 50 stories, or 492 feet) — than New York City. Today’s New Yorkers navigate the vertical world thanks to the city’s 71,000 elevators, which are direct descendants of the ones that Sprague instated at the Postal Telegraph Building.

The pioneering work done by Edison, Sprague, Tesla, Westinghouse, Stanley, and others would provide the blueprint for nearly every electric grid that followed. Their innovations set the stage for a wave of electrification that swept the globe and continues to this day.

Before you go:

Please click that ♡ button, subscribe, and share.

I have opened the comment section on this piece to free and paid subscribers alike.

My dear friend Joe Cunningham, deserves a shoutout. Perhaps more than any other writer, Joe has helped assure that Frank Sprague gets proper recognition for his myriad accomplishments and inventions. For more of Joe’s work on Sprague, read this excellent history of the electrification of Grand Central Terminal, which he co-wrote with John L. Sprague. Additional info on Sprague, including excellent work by John L. Sprague, can be found here.

Wonderful summary and history. I did not know about Frank Sprague or how he changed our world. thank you

Nice article, and I learned something! Did make me pause at one point. "It takes far less cement, wood, and copper to provide living space for an apartment dweller in mid-town Manhattan than it does to house a suburbanite living in Sugar Land, Texas." Sincerely, Suburbanite from Sugar Land.