Gasoline Does The Lindy Effect

The US auto fleet keeps getting older. That means the demand for gasoline and diesel fuel will stay strong for years to come.

Last week, I took my 2012 Acura to my longtime auto repair shop, Rising Sun Automotive, for an oil change. Since we were going on a road trip, I asked the shop manager to check the car out and ensure everything was up to snuff.

A few hours later, they told me the car was due for a brake system flush and needed some suspension work. Thus, what I thought would be a $100 oil change turned into a $1,000 repair bill. But I was glad to pay it. Why? Even though the Acura has about 115,000 miles on the odometer, I like the car. It’s reliable, paid for, runs great, the tires are relatively new, and I am diligent about maintenance.

Furthermore, I have no desire to buy something else. I frequently rent new cars while traveling for speaking engagements, and I have yet to drive a vehicle (of any make) that made me want to buy one. Automakers are spending way too much money on buttons and complicated gadgets and far too little on basic functionality. Plus, new cars cost too much, and as my friends at Rising Sun keep telling me, replacement parts on newer cars are insanely expensive.

My attitude toward maintaining my aging automobile and my grumpiness about new cars aligns with tens of millions of other US motorists. Earlier this year, S&P Global Mobility found that the average age of cars and trucks in the US rose “to a new record of 12.6 years in 2024, up by two months over 2023.” In other words, the vintage of my 2012 Acura TSX is on par with the rest of the US fleet. Here’s the key paragraph from another S&P Global report on the same topic:

New vehicle prices remain prohibitively high for many consumers in the US, with average transaction price reported at US $47,218 in March 2024, according to S&P Global Mobility. Additionally, inflation is proving more persistent than expected and there is trepidation around the shift to electric vehicles. A combination of these factors has resulted in consumers keeping their vehicles on the road longer, driving average age upward. (Emphasis added.)

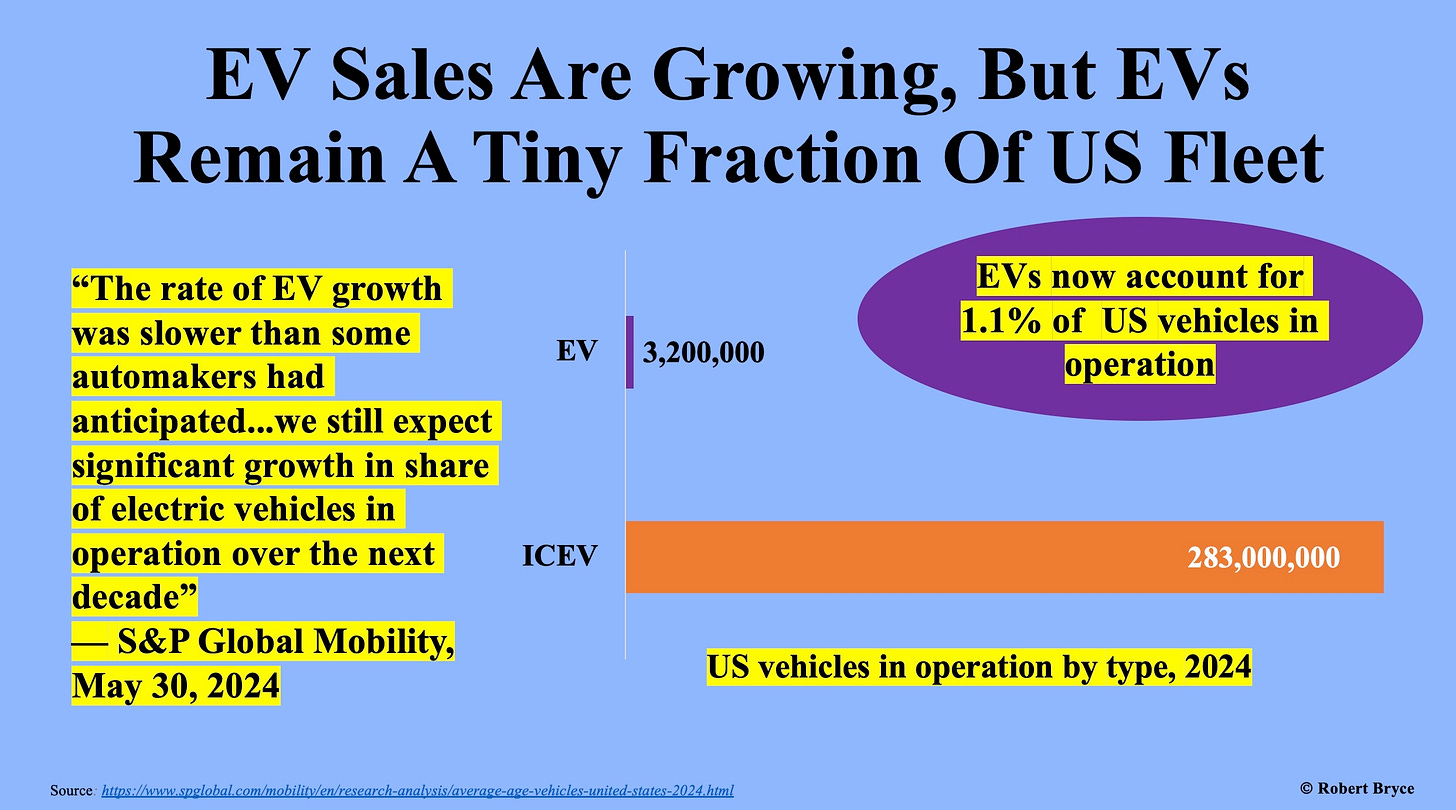

As seen above, there are now 286 million vehicles in operation in the US, and the average passenger car is 14 years old. The combined age of the fleet, which mixes cars and light trucks, is 12.6 years. S&P Global Mobility expects the auto fleet to continue aging through 2028, when some 40% of all the vehicles in the country will be between 6 and 14 years old.

Why does this matter? The S&P numbers show that despite all the never-ending hype about electric vehicles and the pending EPA mandate that could require 70% of all new car sales to be EVs or plug-in hybrids by 2032, the internal combustion engine vehicles now on the road will continue to dominate. That means US demand for gasoline (and diesel fuel) will not decline significantly anytime soon.

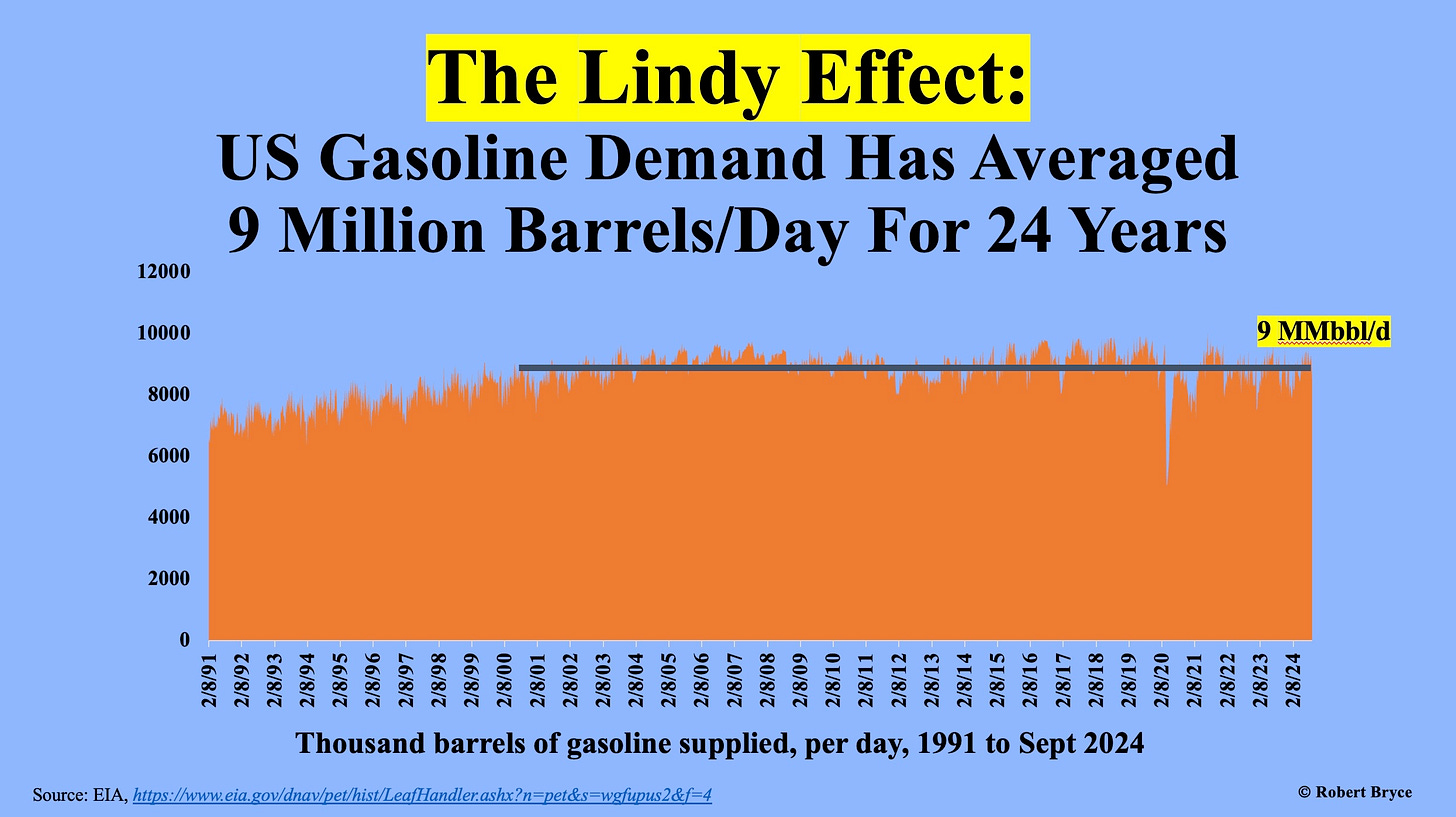

The persistence of old cars like my Acura and the gasoline needed to fuel them can be explained by the Lindy Effect. As I noted last year in “Fire Sale,”

The continued demand for gasoline reflects the Lindy Effect. Author Nassim Nicholas Taleb explained the Lindy Effect in his 2012 book Antifragile: Things That Gain From Disorder. He wrote, “If a book has been in print for 40 years, I can expect it to be in print for another 40 years.” Put another way, the older something is, the more likely it is to be around in the future.

That description fits my car. I bought it new. I’ve kept it for a dozen years, and I plan to keep it for another dozen. For the record, our other cars are even older than the Acura. We also own a 2006 Toyota Tundra and a 2005 4Runner, which we outfitted with a new engine last year. In short, there’s evidence for the aging of the US auto fleet in my own driveway.

The S&P report also contains some stark numbers on EVs. As seen above, of the 286 million vehicles on US roads, about 283 million are internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs). By comparison, there are only about 3.2 million EVs. Thus, EVs now account for slightly more than 1% of all US vehicles in operation. The EV fleet is growing. S&P said EV registrations jumped by 52% in 2023 compared to 2022. But it also noted that “The rate of EV growth was slower than some automakers had anticipated.”

That’s an understatement. All over the world, automakers are junking their EV plans. Earlier this month, Volvo Cars announced it was scrapping its plans to go all-electric by 2030. That comes on the heels of news that Ford Motor Co. has killed plans for an all-electric SUV. GM, Volkswagen, Mercedes, and other big carmakers have also, as the Wall Street Journal put it, “curbed their EV ambitions.”

Even if EV sales pick up, don’t expect a significant drop in oil consumption. Earlier this year, oil analyst Art Berman declared EVs “will have no effect” on overall oil demand. Berman said believing EVs will impact oil use “reflects a fundamental ignorance of the refining process.” He explained:

There is a sequence of products made in a refinery. It’s not an a la carte menu in which you can order diesel, kerosene and jet fuel but tell the waiter to hold the gasoline. Gasoline is produced first. Even if EVs led to less gasoline demand, it would still have to be produced to get the other products. The only way to reduce oil demand is to use less oil, not some distilled fraction of oil. (Emphasis added.)

I’ll end with one more point, and it’s one I have made many times before. Crude oil — and the refined products we get from it — is a miraculous substance. Whether it is energy density, cost, scale, ease of handling, or flexibility, nothing comes close to good old dino juice. It is a nearly perfect fuel for transportation. In short, if oil didn’t exist, we’d have to invent it.

In an era where the knuckleheads from Just Stop Oil are getting headlines for their soup-throwing hijinks, that’s a reality that some people might consider an inconvenient truth.

Before you go:

Please click that ♡ button, share, and subscribe.

I would get the same look of amazement when I said I have been married for 35 yrs as when I said I had 235,000 miles on my SUV. Sadly, it was a mechanic’s error that finally put her in the ground - I truly loved that car, maybe just as much as my husband. We’d been through a lot. What’s the key? Maintenance - in both cases.

"Automakers are spending way too much money on buttons and complicated gadgets"

Boy, do I ever agree with that!