Nuclear Now? Part 2

Big Tech and Big Banks are jumping on the nuclear energy bandwagon. But the nuclear revival won't happen quickly and a massive shakeout looms.

After decades of decline, the US nuclear energy sector has, almost overnight, become the hottest topic in the electricity business. Here’s a quick review of the significant nuclear news over the past six months.

Last Monday, 14 of the world’s biggest financial institutions met in the Rainbow Room at Rockefeller Center to announce they would be lending money for new nuclear energy projects. They said they will back the goal set during the COP 28 meeting last year in Dubai to triple global nuclear energy capacity by 2050.

Earlier this month, tech giant Microsoft and Constellation Energy announced a deal under which the latter will spend some $1.6 billion to restart the Unit 1 reactor at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania. That reactor was shuttered in 2019. When the Unit 1 reactor comes online sometime in 2028, Microsoft will use the juice to power data centers, including those doing AI. Also this month, Oracle said it will build a data center powered by three small modular reactors (SMRs). The company didn’t specify the location of the project or the company that would be providing the reactors.

In August, Holtec International said it plans to restart the 800-megawatt reactor at the Palisades Power Plant in Michigan by the end of next year. If successful, the now-shuttered reactor would be the first to restart operations in US history. Holtec’s effort is backed by $1.5 billion in loans from the Department of Energy and a $300 million grant from the state of Michigan.

In March, Amazon Web Services bought a 960-MW data center campus from Talen Energy that is powered by the 2,500-MW Susquehanna nuclear plant. An Amazon spokesperson said the move was being made to “supplement our wind and solar energy projects, which depend on weather conditions to generate energy.”

All these moves are welcome. They are also proof that support for nuclear energy has — finally! — become mainstream. Last week, everyone’s favorite green chicken, Doomberg, declared that the announcement “almost certainly marks a critical inflection point that will finally give investors around the world the confidence to pour much-needed capital into new nuclear deployment at scale.” Doomberg quoted Mark Nelson of the Radiant Energy Group, who said Monday’s announcement was “a watershed moment for nuclear power.” Nelson also made a critical point, (and one that I’ve been making for years). He said: “Electricity is not, and never was, a commodity.”

Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Nikki Hsu echoed that same point: “People say power is just a commodity. Nuclear power doesn’t seem to be a commodity now.”

While the shift in sentiment among investors and policymakers is welcome (and long overdue), we have to be sober about the current state of the nuclear sector and where it’s going. More than two dozen companies are vying to commercialize SMRs. Others are betting on the larger, gigawatt-size reactors. The potential rewards for the winning companies are apparent. The US electricity sector alone sells nearly 4,000 terawatt-hours of juice and generates about $500 billion in revenue every year. The global electricity sector takes in some $1.6 trillion annually.

But obstacles abound. To understand them, I contacted two veterans of the nuclear sector, Chris Gadomski, head of nuclear research at Bloomberg New Energy Finance, and Ray Rothrock, a California-based venture capitalist who has invested in 11 nuclear startups. Here’s what they had to say.

Before turning to Gadomski and Rothrock, it’s important to note that one of the biggest challenges facing new nuclear in the US are the subsidies for alt-energy, which dwarf those given to hydrocarbons and nuclear power.

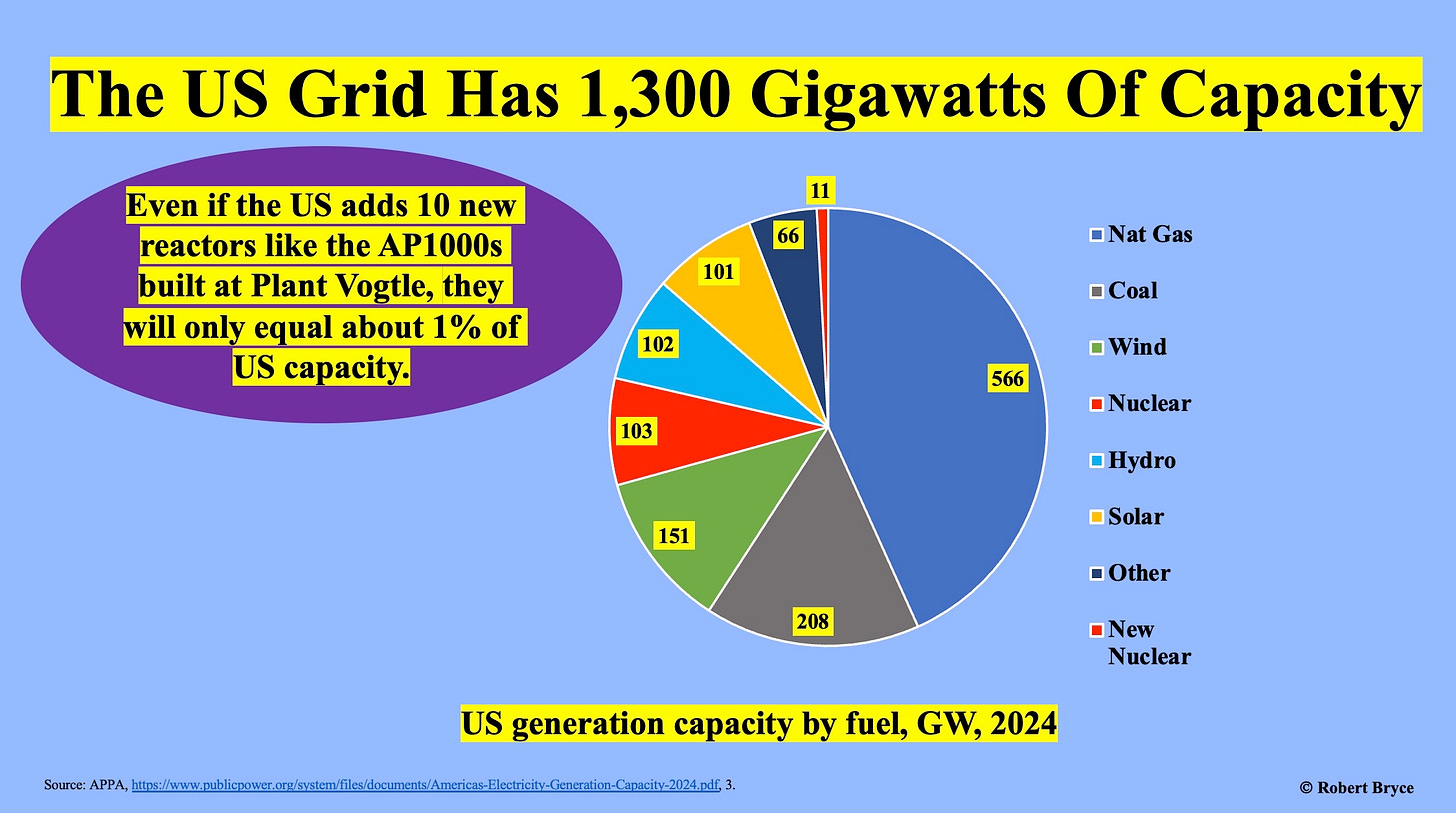

As I reported last September, the solar and wind sectors are gorging on federal tax credits. As seen above, in 2022, solar energy producers got about 300 times more in federal tax incentives per unit of energy produced than nuclear producers. Wind energy producers got 70 times more. Those massive subsidies are driving the spending on the grid. According to data published by the American Public Power Association, between 2016 and 2023, 64% of all the generation capacity added to the US grid was wind and solar. Nuclear accounted for just 1%. Those alt-energy subsidies distort wholesale power markets and encourage utilities and power producers to shutter thermal power plants and build more weather-dependent generation capacity.

Although the nuclear sector is having its day in the sun, it’s also clear that a massive shakeout looms. At least 26 companies — some startups, some state-backed nuclear giants — are developing or deploying SMRs. Here’s the list I compiled:

Steady Energy, Oklo, NuScale Power, Kairos Power, Rolls-Royce, GE Hitachi, Westinghouse, TerraPower, Terrestrial Energy, ARC Clean Technology, X-energy, General Atomics, Holtec International, Aalo, Rosatom, China National Nuclear Corporation, Last Energy, Blue Energy, Radiant Nuclear, Thorcon, Flibe Energy, Moltex Energy, Ultra Safe Nuclear, Natura Resources, NuWard (a division of EDF), and Newcleo. (Please add any SMR company not shown here in the comments section.)

Most of these companies are paper reactor outfits. A handful of them are moving dirt on their prospective sites. All are working to garner the capital, contracts, and regulatory approvals needed to permit and build their reactors. While some designs are more promising than others, only a few of these companies will ever build an SMR, much less make a profitable business out of doing so.

Rothrock, who has a degree in nuclear engineering, expects that “only two or three,” of the SMR companies will succeed. He didn’t predict which ones would win, but he believes reactor designs that rely on water cooling may have some advantages in getting regulatory approvals. Rothrock also said that the SMR companies that are backed by deep-pocketed investors could have an advantage, but it won’t be a decisive one. “Money doesn’t equal speed,” he said. Well-capitalized companies will have more staying power, but they won’t be able to get their projects through the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s approval process any faster than their rivals, he said.

Rothrock said the recent announcements by Microsoft/Constellation and Holtec to reopen shuttered reactors are heartening. But he also noted, “Turning old plants back on is the only thing we have right now.” Rothrock expects SMRs to start coming online in the US in the 2030s.

Gadomski was equally cautious. He said the goal to triple global nuclear capacity is “an admirable and ambitious target,” but it will be “burdened by significant political, economic and technical challenges.” He continued, pointing out that many of the lenders who pledged support for nuclear “are tied to nations with robust nuclear ambitions, think Canada, France, the UAE, and the UK. It is not surprising, nor a huge leap, therefore, that a large French bank with existing ties to the national nuclear operator Électricité de France would express support for financing more nuclear.”

Like Rothrock, Gadomski expects the first SMRs will come online in the US in the 2030s. That, in turn, means new nuclear plants won’t make a significant dent in the domestic generation mix for many years. As seen above, the US now has about 1,300 gigawatts (GW) of installed generation capacity. Of that, about 103 GW is nuclear. Even if the US added 10 more reactors the size of the two AP1000s that were recently completed at Plant Vogtle, in Georgia, doing so would only add about 11 GW to the US fleet. (The two reactors at Vogtle cost $34 billion and took 10 years to build.) Adding 11 GW of nuclear capacity would be a great start, but it won’t be a game-changer on a US grid with 1,300 GW of capacity.1

I asked Gadomski if the recent change in sentiment by Big Tech and Big Banks will catalyze significant new investment. He replied:

The challenge is not so much in the availability of financing, but rather in addressing the underlying cost and construction issues that make new nuclear such an undertaking. If recent nuclear construction in Western markets did not have such a dismal schedule and cost-overrun track record, financing would be less of a challenge. The Chinese can build a nuclear reactor for one-fifth the cost on a per-kilowatt-electric basis than what Plant Vogtle cost. Recent and ongoing construction in Finland, France and the UK demonstrates schedule and budget overruns as well. That is one reason the Koreans have won a bid for building two 1,000-MW reactors in the Czech Republic for $17 billion. (Emphasis added.)

I also asked Gadomski to handicap the global nuclear race. China is now building five times more nuclear capacity than any other country (29.6 GW). Other than China, which countries will be the first to deploy new reactors? He replied:

BNEF expects the first new reactor in North America to come online in Ontario, Canada, around 2030. They will build a 300-MW General Electric Hitachi SMR for which the company is simultaneously developing opportunities in other parts of Canada and in Eastern Europe. Poland, like other countries in that region, rely heavily on fossil fuels...There is also a lot of interest in the Middle East, where Russia is building four reactors each in Egypt and Turkey. India’s reliance on coal presents that nation as a logical candidate for more nuclear. Historically, development there has been slow.

Cost will be an ongoing challenge. The restarts in Pennsylvania and Michigan won’t necessarily result in cheap power. Bloomberg Intelligence estimates Microsoft will pay at least $100 per megawatt-hour for the electricity from the restarted reactor at Three Mile Island. Another estimate from Jefferies LLC put the figure at $112 per MWh. Last year, Oglethorpe Power Corporation, which owns part of the new reactors at Vogtle, said it would pay about $140 per MWh for the electricity it gets from the reactors. That’s significantly more expensive than the wholesale power prices that prevailed across the US last year.

Of course, there are other challenges, including competition from heavily subsidized alt-energy, low-cost natural gas, and the well-funded dullards who work for the anti-nuclear industry. In July, Ken Braun, a sharp-eyed reporter at Capital Research Center, found that the US anti-nuclear NGOs have combined annual revenues of “at least $2.5 billion.” That’s an increase of about $200 million from the estimate Braun published in 2023.

The punchline here is obvious: There’s much to celebrate with these recent announcements. But the US nuclear sector withered over a period of decades. It will take decades to build it back up.

I’ll end with a salient point from Rothrock. “Nuclear energy is now a strategic issue,” he told me. It’s clear that the US needs to generate a lot more electricity and that the importance of the grid, from a national security standpoint, is more evident than ever. But expanding the nuclear sector will, he said, require “strategic long-term thinking.”

Let’s hope we see more strategic long-term thinking from policymakers.

A reminder: I’m going paid on October 1

I know that some readers were disappointed to learn that I'm going to a paid model. I kept my Substack free for as long as I could. But I'm an independent reporter. My only source of income is from speaking engagements. I love public speaking, and I’m good at it. I also love meeting people across America (and farmers and ranchers in particular). But the speaking business requires a ton of travel. Going paid on Substack will, I hope, provide a reliable income stream and allow me to spend more time writing, researching, and, engaging with readers. Thanks again for your support.

Before you go:

You will do me a favor by clicking that ♡ button. And while you’re at it, please share and subscribe.

Gadomski also pointed out that no new reactors are currently being built in the US. However, TerraPower has started constructing the non-nuclear part of its plant in Kemmerer, Wyoming. Kairos has done the same at Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

The note in the graphic says that adding 10 new 1,000MW reactors will add only 1% to total US capacity, but fails to note that it would add approximately 5% to total generation and all of the generation would be delivered when needed, not when the sun shines or the wind blows. Only 54 nuclear power plants (94 reactors) in the US currently produce 21% of the electricity. More than 2,500 utility scale solar sites produce only 3.4% of our electricity and 1,500 wind projects with over 71,000 turbines produce only 10% of our electricity. There are hundreds of decommissioned coal power plant sites that could easily host new gigawatt scale nuclear reactors. They are all brownfield industrial sites with access to cooling water and existing grid connections. Most are located in or near major load centers. The main issue with cost and schedule overruns is the NRC and its zero risk tolerance approach developed in the 1970's. This needs to be updated to the current state of technology.

A real turning point will be deciding to build more AP1000s. The cost runups of Vogtle 3 and 4 gave people the false impression that there is flaw. To get costs down requires building many reactors of the same design in succession. SMRs are not likely, in the long run, to be as cheap as large reactors. It will be a tragedy if lessons learned on Vogtle are lost, and the skilled workers are dissipated.

The eventual failure of wind and solar will bring about the nuclear renaissance, but with education it can hopefully be accelerated. Wind and solar subsidies are a perfect example of how subsidies can backfire. As is often the case, the loser was picked over the winner.