Swedish rare earths won’t dent China’s monopoly for decades

The new discovery is big, but turning ore into magnets is the real challenge.

Last week, the Swedish government announced the discovery of a huge rare earth deposit. Heralded as the largest such discovery in Europe, it holds an estimated 1 million metric tons of rare earth oxides, according to LKAB, the government-owned mining firm.

The discovery of the Per Geijer deposit, located next to the Kiruna Mine in northern Sweden, is significant because rare earth elements—also known as the lanthanides—are key ingredients in alt-energy technologies. But China has a near-monopoly on the global supply chain for both the rare earths themselves and the sintered magnets that are critical to two of the highest-profile alt-energy technologies: Electric vehicles and wind turbines. Both use high-output magnets that contain neodymium, one of the most important of the rare earths. Neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) magnets are often doped with two other rare earths elements, praseodymium, and terbium, so they perform better in high-temperature environments.

Last year, the Department of Energy issued a stark report titled “Rare Earth Permanent Magnets: Supply Chain Deep Dive Assessment.” This paragraph sums up the problem:

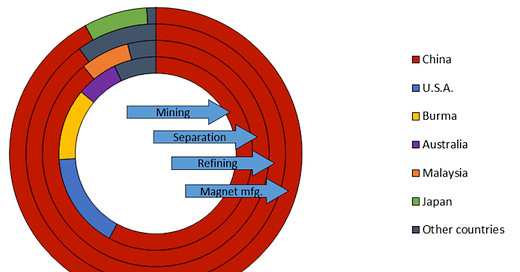

While the mine production of RE elements has diversified since 2012, China still accounts for an estimated 89 percent of total RE separation capacity, an estimated 90 percent of total metal refining capacity, and approximately 92 percent of global sintered NdFeB magnet manufacturing. The United States, by comparison, accounted for about 16 percent of total RE mine production in 2020 (up from less than 1 percent in 2012), but still is not separating rare earths or refining them into metals, and produces less than 1% of the world’s NdFeB magnets, although there are plans to add domestic capacity in each of these areas.

Read that again: China controls “approximately 92 percent of global sintered NdFeB magnet manufacturing.” The key graphic from that report is at the top of this page.

Thus, while Sweden may be able to ramp up the mining of rare earths, that is only a part of the challenge. The U.S. and other countries don’t have the capacity needed to produce magnets from rare earths. Furthermore, the timeline for the new mine in Sweden is so far in the future that it won’t make a difference to the global rare earth supply for at least a decade -- and that is the best-case scenario. (In my fourth book, Power Hungry, published in 2010, I have a chapter on rare earths and China’s control over them. It’s titled: “Myth: Going ‘Green’ Will Reduce Imports of Strategic Commodities and Create ‘Green’ Jobs.”)

When LKAB made the announcement, the company’s president and CEO Jan Moström, warned that “it will take several years to investigate the deposit and the conditions for profitably and sustainably mining it. We are humbled by the challenges surrounding land use and impacts that exist to develop this into a mine and that will need to be analysed to see how to avoid, minimize and compensate for it. Only then can we proceed with an environmental review application and apply for a permit.” He continued, saying “If we look at how other permit processes have worked within our industry, it will be at least 10 to 15 years before we can actually begin mining and deliver raw materials to the market.”

Remember, that’s 10 to 15 years to get the raw materials. The materials will then have to be processed and turned into magnets. Last April, James Kennedy, the president of ThREE Consulting, a St. Louis-based firm that specializes in rare earth elements and critical minerals, came on the Power Hungry Podcast to talk about rare earths and the alt-energy sector’s dependence on China. He said that China is using its dominance over technology metals “as geostrategic tools, or weapons.”

Kennedy said that while the U.S. and other countries may ramp up mining, they don’t have enough processing capacity or the ability to turn out large quantities of magnets. (Last September, the Energy Department announced $156 million in funding to help jumpstart the domestic processing.) That means any rare earth ore produced from domestic mines (the U.S. has just one active mine, in Mountain Pass, California) must be shipped to China for processing. About that issue, Kennedy told me “We’re mining rare earths for China. They’re converting them to metals and magnets, and then they’re selling them back to us. They’re deciding who gets them and who doesn’t. And that will be the case from now [to] 2030, and now to 2050. Because the way China can manage its monopoly is it focuses all of its subsidies specifically on the separation of rare earths, and much more specifically, on the conversion of pure oxides to metallics...And the subsidies there are so significant, that no company outside of China has ever been economically competitive.”

In summary, the Swedish discovery is important. But it’s not going to change global dependence on Chinese supply chains anytime soon. Back in 1992, Deng Xiaoping said “the Middle East has oil. China has rare earths. We must take full advantage of this resource.” That’s exactly what China has done. Changing that reality will take decades.

Want more content?

Subscribe to the Power Hungry Podcast or watch it on YouTube

Watch Juice. It’s now available for free on YouTube

Buy A Question of Power: Electricity and the Wealth of Nations (& give it a good review)

Follow me on Twitter

Follow me on TikTok

Need a speaker for your conference, class, or webinar? Ping me!

Another great post, Robert.

Re: Admin's new loan guarantee for the lithium mine in NV, it occurred to us to hope it's only extraction and not processing. The latter takes a lot of water. In case it didn't occur to DoE or the Admin, NV has been just a bit stretched for water of late.

In 15 years (read 20 years) the impossibility and fraud of "green energy" and going all electric will be exposed and over. Or our economies will be so obliterated it won't matter.

That the left is willing to destroy the environment to "save it" tells you everything you need to know about the veracity of their claims.