Women, Electrified

Here's the second section of my paper on electrification that was published last week by the Alliance For Responsible Citizenship

Here is another installment of the paper I wrote for the Alliance For Responsible Citizenship. It covers the sections on electricity’s importance to women and girls, and why coal continues to be a dominant fuel for power generation around the world. If you want to read the entire report, it’s available here.

Women, Electrified

Electricity is essential for all human beings. But it is particularly beneficial for women and girls because it frees them from the drudgery of energy poverty. Put short, electricity emancipates women and girls from the pump, the stove, and the washtub.

Numerous academic studies have shown the positive effect electrification has on women and girls. A 2002 study in Bangladesh by Abul Barkat, an economist at the University of Dhaka, found that the literacy rate for females in villages with electricity was 31% higher than it was in villages that lacked electricity. The study concluded that the availability of electricity has a “significant influence on education, especially on the quality of education. This influence is much more pronounced among the poor and girls in the electrified households than the poor and girls in non-electrified households.”

A 2010 study on post-apartheid electrification in South Africa found that “employment grows in places that get new access to electricity.” This was particularly true for women. The study found that electrification led to “large increases in the use of electric lighting and cooking, and reductions in wood-fuelled cooking over a five-year period, as well as a 9.5 percentage point increase in female employment.”

A 2012 study of rural electrification in India concluded that the availability of electricity had a significant impact on schooling for girls, finding:

“…electrification access increases school enrolment by about 6% for boys and 7.4% for girls. It also increases weekly study time by more than an hour, and the increase is slightly more for girls than boys. As a result of more study hours, children from households with electricity can be expected to perform better than their peers living in households without electricity.”

The same study found that “The impact of electrification on labour supply is positive for both men and women; that is, household access to electricity increases employment hours by more than 17% for women and only 1.5% for men.” Further, the study found that electrification reduces the overall poverty rate by 13.3%, and it concluded that “these findings indicate electrification’s substantial positive effect on overall household welfare.”

Complex studies are not needed to show that extreme shortages of electricity are a common factor in nearly every country where women and girls are vulnerable to illiteracy and child marriage. World Bank data shows that the countries with the highest female illiteracy rates are all in the Unplugged world. If you are a female in an impoverished country and do not have access to electricity, you are, effectively, a slave to the physical chores of the household: hauling water, making fires, grinding grain, and washing clothes. In 2014, the United Nations Children’s Fund released its “State of the World’s Children” report. It is a sobering document that details the plight of children around the world, and in particular, the plight of girls. Among the aspects that UNICEF examined was the issue of child marriage, that is, cases in which girls are married before age 18.

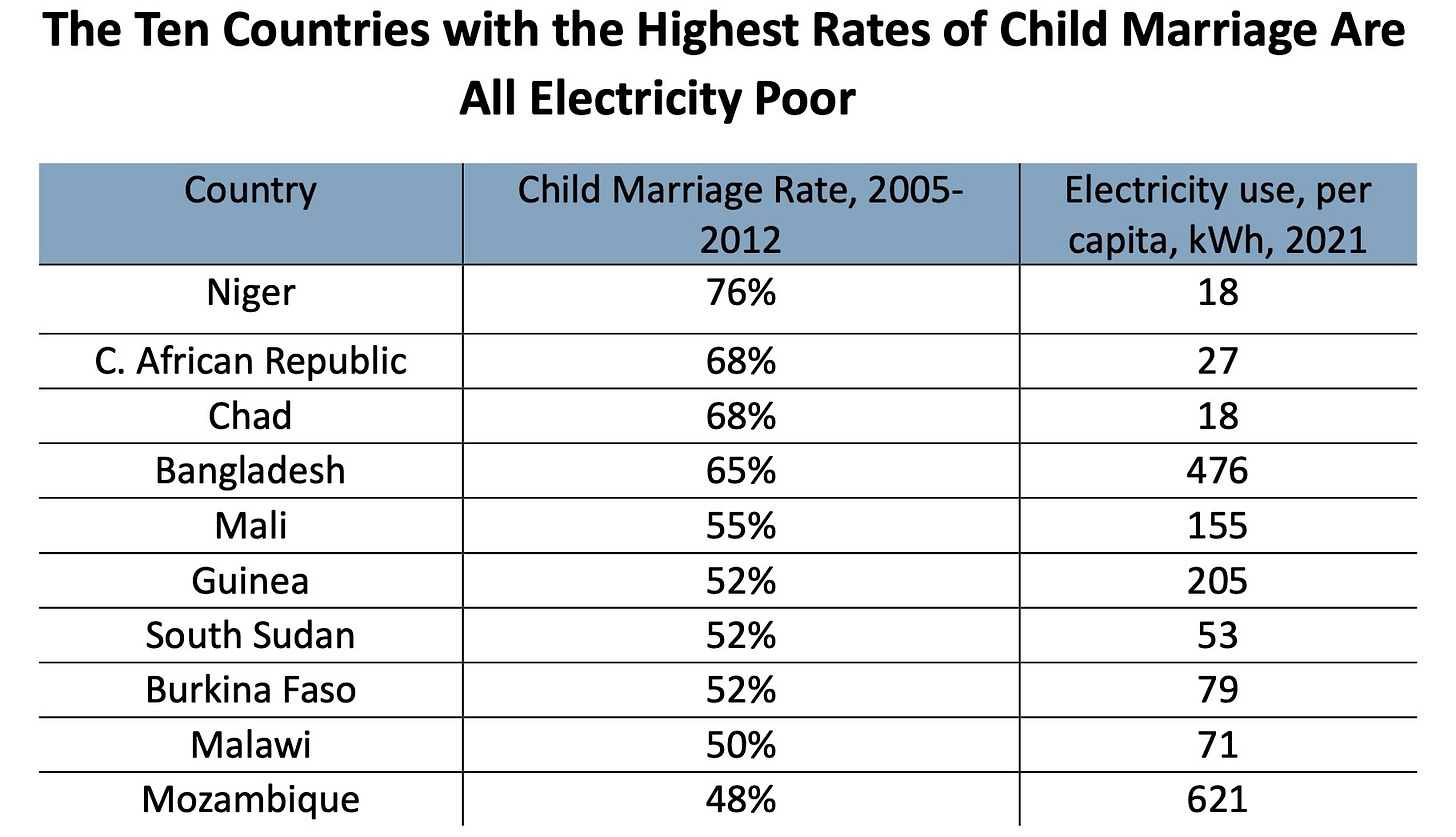

Figure 5

As seen in the graphic above, the 10 countries with the highest rates of child marriage are all in the Unplugged World. Furthermore, among those 10 countries, the rates of child marriage tend to be highest in the places where per capita electricity use is lowest. For instance, in Niger, between 2005 and 2012, according to UNICEF, about 28% of girls were married by the age of 15. By the age of 18, some 76% were married. As seen in the graphic and the Appendix, per capita electricity use in Niger is now about 18 kilowatt-hours per year. In the Central African Republic, electricity use is just 37 kilowatt-hours per capita per year. In Chad, it is 18 kilowatt-hours. In those three countries, the electricity usage rates are so small as to be insignificant. For example, a resident of Chad, who can use just 18 kilowatt-hours of electricity per annum, would, over the course of a year, only have enough power to boil a kettle of water every four days.

Electricity matters to women and girls because electric stoves can reduce the amount of cooking done with solid fuels. Indoor air pollution is a major cause of death for women and girls in developing countries.

Pivotal research on this problem was done by the late Kirk R. Smith, a professor of global environmental health at the University of California, Berkeley. Smith estimated that indoor cookstoves that use biomass released the smoke equivalent of 400 cigarettes per hour. In 2002, he wrote a piece for Science magazine titled “In Praise of Petroleum?” in which he challenged the notion that “for the poor as for everyone else, only renewable energy sources qualify as sustainable.” He pointed out that clean-burning hydrocarbons like butane and propane can reduce indoor air pollution and provide “high-quality energy services” for poor households.

During a 2009 interview, Smith told the author of this paper, “Poor women in rural areas of developing countries are about as low on the totem pole, globally, as you can get,” Smith said. “They don’t have anybody speaking for them. They don’t have their own Sierra Club or whatever.” Smith, who died in 2020, said, “Even if you were to substitute LPG [liquified petroleum gas, i.e., propane or butane] for all of the biomass used for cooking in the world, it would have very little impact on overall resources.” He continued: “Why ask the poor to take on the need to use fancy, new novel untested, renewable energy devices when we have something that’s good for them? They have many other needs. And this is a great thing for them.”

In 2007, the World Health Organization estimated that indoor air pollution was killing about 500,000 people in India every year, most of them women and children. The agency found that air pollution levels in some kitchens in rural India were 30 times higher than the recommended level and that the pollution was six times as bad as that found in New Delhi. Worldwide, as many as 1.6 million people per year die premature deaths due to indoor air pollution.

A 2021 study found that the “morbidity and mortality caused by exposure to household air pollution from the use of solid fuels remain a significant public health burden in many developing countries of the world.” According to the study, “[i]t is estimated that globally, about 3 billion people mostly in low-income countries use solid fuels for domestic cooking and heating with close to 646 million of these people living in sub-Saharan Africa, and this number is expected to continue to rise over the years.” It continued, “The use of solid (biomass) fuels and kerosene exposes household members to health-damaging pollutants...Each year, close to 4 million people die prematurely from illness attributed to household air pollution from inefficient cooking practices.”

The plight of women was a primary motivator for the politicians who pushed for rural electrification in the United States during the 1930s. One of the biggest proponents of electrification was George Norris, a flinty Nebraskan, who helped push the Rural Electrification Act of 1935 through Congress. In his 1945 autobiography, Fighting Liberal, Norris wrote vividly about growing up on a farm. “From boyhood, I had seen first-hand the grim drudgery and grind which had been the common lot of eight generations of American farm women...I knew what it was to take care of the farm chores by the flickering, undependable light of the lantern in the mud and cold rains of the fall, and the snow and icy winds of winter. I had seen the cities gradually acquire a night as light as day.” The full passage continues:

“I knew the heat of those summer days in a farm kitchen…where humidity and blazing sun combined with the stove to create unbearable temperatures. I had seen the drudgery of washing and ironing and sewing without any of the labour-saving electrical devices. I could close my eyes and recall the…unending punishing tasks performed by hundreds of thousands of women…growing old prematurely; dying before their time; conscious of the great gap between their lives and the lives of those whom accident of birth or choice placed in the towns and cities. Why shouldn’t I have been interested in the emancipation of hundreds of thousands of farm women?”

Another New Dealer, Lyndon Johnson, who was born and raised in the hard-scrabble hills of the Texas Hill Country, also deserves credit for the effort to bring electricity to rural America. During his long political career, which included reaching the White House in 1963, Johnson was proud of his efforts to boost rural electrification. For him, the grinding poverty of farm living without electricity was not an abstract notion. He was, as one biographer wrote, “raised by the light of lanterns and cooked for on a wood-burning stove. He had seen his mother scrubbing clothes in a washtub. He knew the insides of outhouses.”

As electricity frees women from the pump, the stove, and the washtub, it allows them to get educated, find jobs, and become active in civil society. Given that fact, it is not surprising that crucial advances in electrification occurred at about the same time women were gaining more political power. A look at the late 19th and early 20th centuries shows that women’s suffrage gained critical momentum during the same decades that the world’s major cities were being electrified. For example, 1893 was a turning point for the suffrage movement in America. That year, Colorado became the first state in the United States to adopt an amendment granting women the right to vote. That same year, at the Columbian Exhibition in Chicago, George Westinghouse proved that the alternating current would become the standard method of distributing electricity to customers. Also, in 1893—11 years after Edison began producing electricity in Lower Manhattan—women in New Zealand were granted the right to vote. In 1902, Australia gave women the right to vote. In 1906, Finland did the same.

Of course, numerous factors contributed to the success of the suffrage movement. But it is also clear that electrification paralleled the rise of women in society. As electrification swept around the globe, women began leaving the isolation and energy poverty of rural farms and ranches for better opportunities in brightly lit cities. As women got more jobs and independence, so did their desire for more power in the workplace and political office.

Today, policymakers should make reducing the death toll from indoor air pollution in developing countries a top priority. Electric cookstoves, and better availability of LPG (liquefied petroleum gas) in those countries, could save hundreds of thousands of lives per year.

So, what are the keys to bringing more electricity to developing countries so that more women and girls have more opportunities? The next section will discuss some of the difficult realities that policymakers face as they consider the global electricity landscape.

Powering Up

Globalisation can be seen in nearly every commodity, from coffee to tennis rackets and beer to automobiles. However globalization does not play much of a role in the electricity sector. Yes, there is plenty of trade in the fuels we use to produce electricity, including coal, natural gas, oil, and uranium. In addition, there is a booming global trade in solar panels, wind turbines, gas turbines, reciprocating engines, poles, and transformers. But very little electricity gets shipped across international borders. (Several countries in the European Union are the obvious exception to this fact.) The reason so little electricity gets traded across borders is that politicians are not willing to cede control of such a vital service to a foreign entity, no matter how friendly it might be. This lack of international trade means that countries must be largely self-sufficient in electricity generation. That, in turn, means that countries must choose the fuels and generation technologies that can assure affordable and reliable power for their citizens.

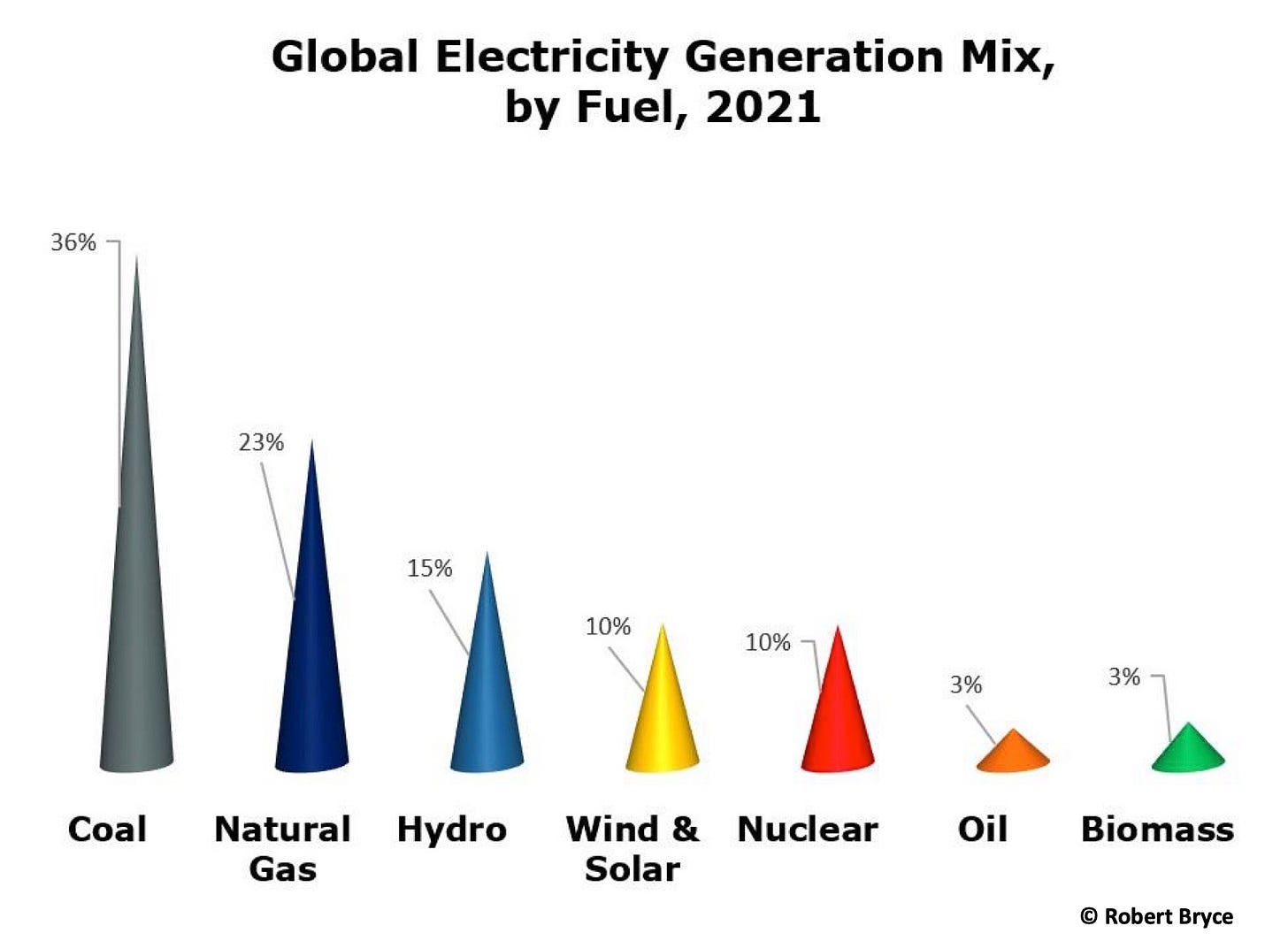

Figure 6

Over the past decade, renewable energy has grown rapidly in developing and advanced economies. That growth will likely continue. But as seen in the graphic above, hydrocarbons continue to dominate. Power plants that burn natural gas and coal provide about 59% of the world’s electricity. By itself, coal accounts for 36%. In fact, coal’s share of global generation has stayed between 36% and 40% since 1985, and that dominance will likely endure for decades to come.

In December 2022, the IEA reported that coal use was at an all-time high and that global coal demand would not peak until 2025 at the earliest. The Paris-based agency reported that “the current energy crisis has forced some countries to increase their reliance on coal in spite of climate and energy targets.” The agency also predicted that global coal demand will likely plateau but is unlikely to peak until 2025, noting:

“A convergence of factors is supporting an increase in coal demand. First, tight natural gas supplies and the resulting high gas prices are driving some countries and companies to turn to relatively cheaper coal. Second, heat waves and droughts in some regions of the world drove up electricity demand and reduced hydropower generation, creating a gap that had to be filled by mostly dispatchable thermal power plants. Last, nuclear power generation was exceptionally weak in 2022, especially in Europe, where France had to shut down a significant portion of its nuclear capacity for maintenance.”

Also notable in that report was this line about the world’s most populous country: “India’s coal consumption has doubled since 2007 at an annual growth rate of 6%—and it is set to continue to be the growth engine of global coal demand.”[1]

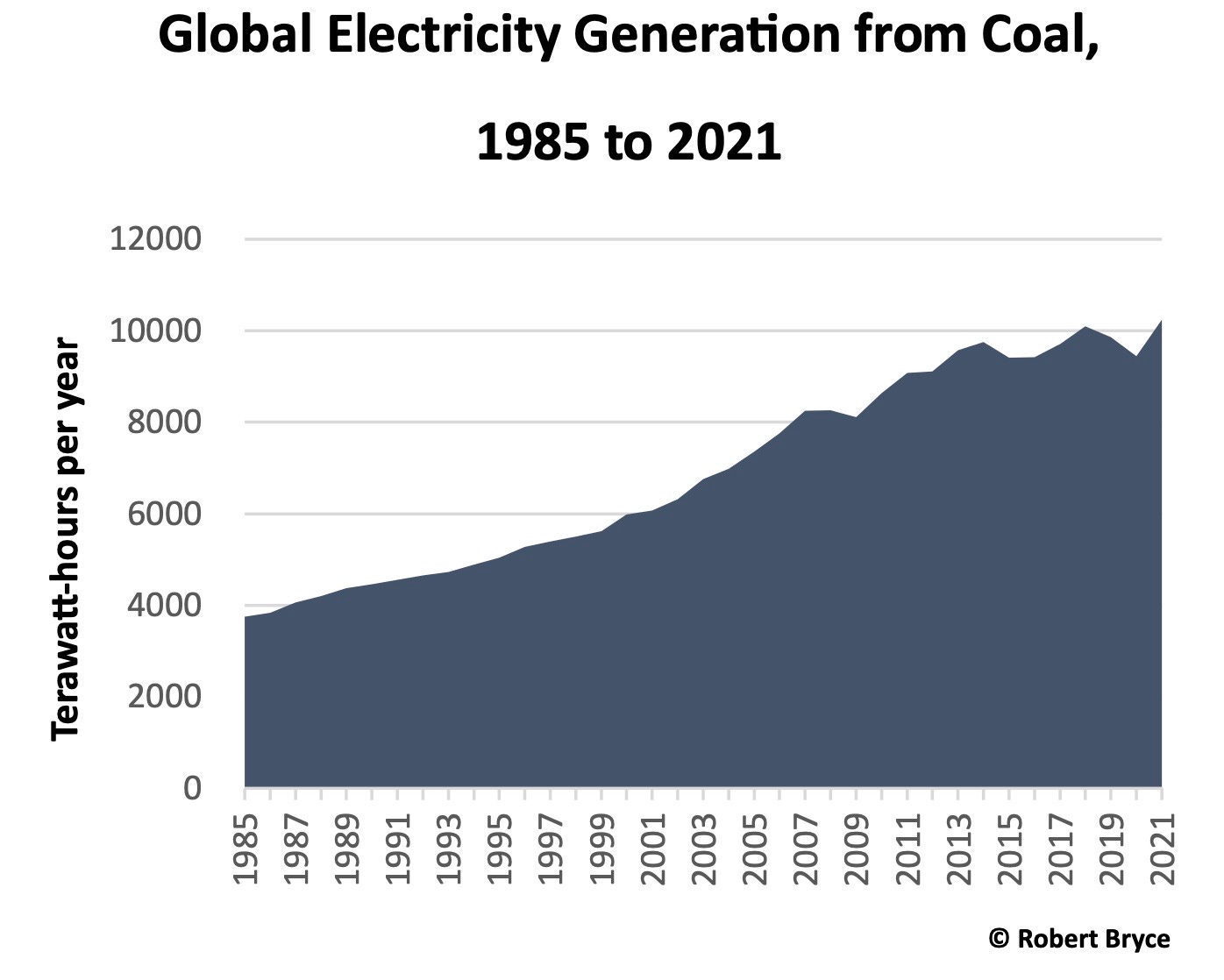

Figure 7

The continuing importance of coal for electricity production, which has grown almost every year since 1985, can be understood by reviewing several recent events in Unplugged countries.

On 23 January 2023, Pakistan was hit by a nationwide blackout that left about 220 million people in the dark. The blackout came just a few days after Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif had ordered all federal departments in Pakistan to slash their electricity use by 30%. The government also ordered all markets to close by 8.30 p.m. and restaurants to be shuttered by 10 p.m. The blackout hit at about 7:30 a.m. on a Monday, and was blamed on a “major breakdown” in the national grid. A government official said there had been a “fluctuation in voltage” and that “power generating units were shut down one by one due to cascading impact.”

The January blackout was only the latest in a long series of outages in Pakistan. In October 2022, southern parts of the country were hit by a blackout that lasted about 12 hours. In January 2021, a blackout “plunged all of Pakistan’s major cities into darkness, including the capital Islamabad, Karachi and the second-largest city, Lahore. There were no immediate reports of disruption at hospitals, which often rely on backup generators. A water and power ministry spokesman said electricity had been restored to some parts of the country but many areas in Lahore and Karachi were still waiting.” In 2018, a power outage hit most of eastern and northern Pakistan.

Pakistan’s shaky electric grid led to a predictable response from the Pakistani government. In February 2023, it announced it would quit importing liquified natural gas (“LNG”) for its power sector and would instead quadruple the size of its domestic coal-fired generation capacity. The move came after a surge in global prices of LNG in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Pakistan Energy Minister Khurram Dastgir Khan told Reuters, “LNG is no longer part of the long-term plan,” and that the country would increase its domestic coal-fired power capacity to 10 gigawatts, a four-fold increase over the 2.3 gigawatts of capacity now in place. As Reuters explained, “Pakistan’s plan to switch to coal to provide its citizens reliable electricity underscores challenges in drafting effective decarbonization strategies.”

In Bangladesh, fuel and foreign currency shortages have resulted in the country’s worst electricity crisis in a decade. In mid-June, industrial and residential consumers were experiencing blackouts lasting 10 to 12 hours per day. During the first five months of 2023, the Bangladesh grid operator was forced to cut power for 114 days. For comparison, the grid operator cut power on 113 days in all of 2022. Bangladesh, which is among the world’s poorest countries, will be burning more coal in the coming years. In 2022, the country commissioned a new 1,010-megawatt coal-fired power plant.

The most populous country in the Unplugged World, India, continues to embrace coal. In late 2022, the Indian government launched its biggest-ever auction for coal mining. According to an article in The Hindu Business Line, the government offered “133 blocks for auction, of which 71 are new mines and 62 are rolling over from earlier tranches of commercial auctions.” The auctions came just a few weeks after Power Minister Raj Kumar Singh said that India would add as much as 56 gigawatts of new coal-fired generation capacity by 2030. That would be an increase of about 25% over the country’s current installed base of about 204 gigawatts of coal-fuelled generation. In explaining the move, Singh said “My bottom line is I will not compromise with my growth...Power needs to remain available.”

Of course, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and India are not the only countries that have turned to coal in recent years. So has Germany. In October 2022, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz announced that Germany was reopening five power plants that burn lignite, a low-rank coal. Furthermore, the country’s need for lignite to keep its power plants operating was so critical that the German utility company, RWE, dismantled the Keyenberg wind project in the western part of the country to make room for the expansion of the Garzweiler coal mine. Lignite from Garzweiler fuels the Neurath C power plant, which is one of the power plants being brought back online. A spokesperson for RWE told the Guardian newspaper that “We realize this comes across as paradoxical.”

Paradoxical or not, the moves by these many countries provide clear evidence of the Iron Law of Electricity. The Iron Law of Electricity says people, businesses, and countries will do whatever they have to do to get the electricity they need. And that, of course, includes burning more coal.

Over the past six years, I have seen the Iron Law of Electricity at work with my own eyes. I have watched as people steal electricity in India, pay the generator mafia in Lebanon, and run small gasoline-fuelled generators in Louisiana to make sure they have the electricity they need to refrigerate their food, cook their dinner, and heat or cool their homes. The Iron Law of Electricity says that no one will willingly sit in the dark. Instead, people will find a way to get the electricity they need because energy—and electricity in particular—means life. The absence of energy means death. Those facts show why coal will not go away any time soon, particularly in Asia.

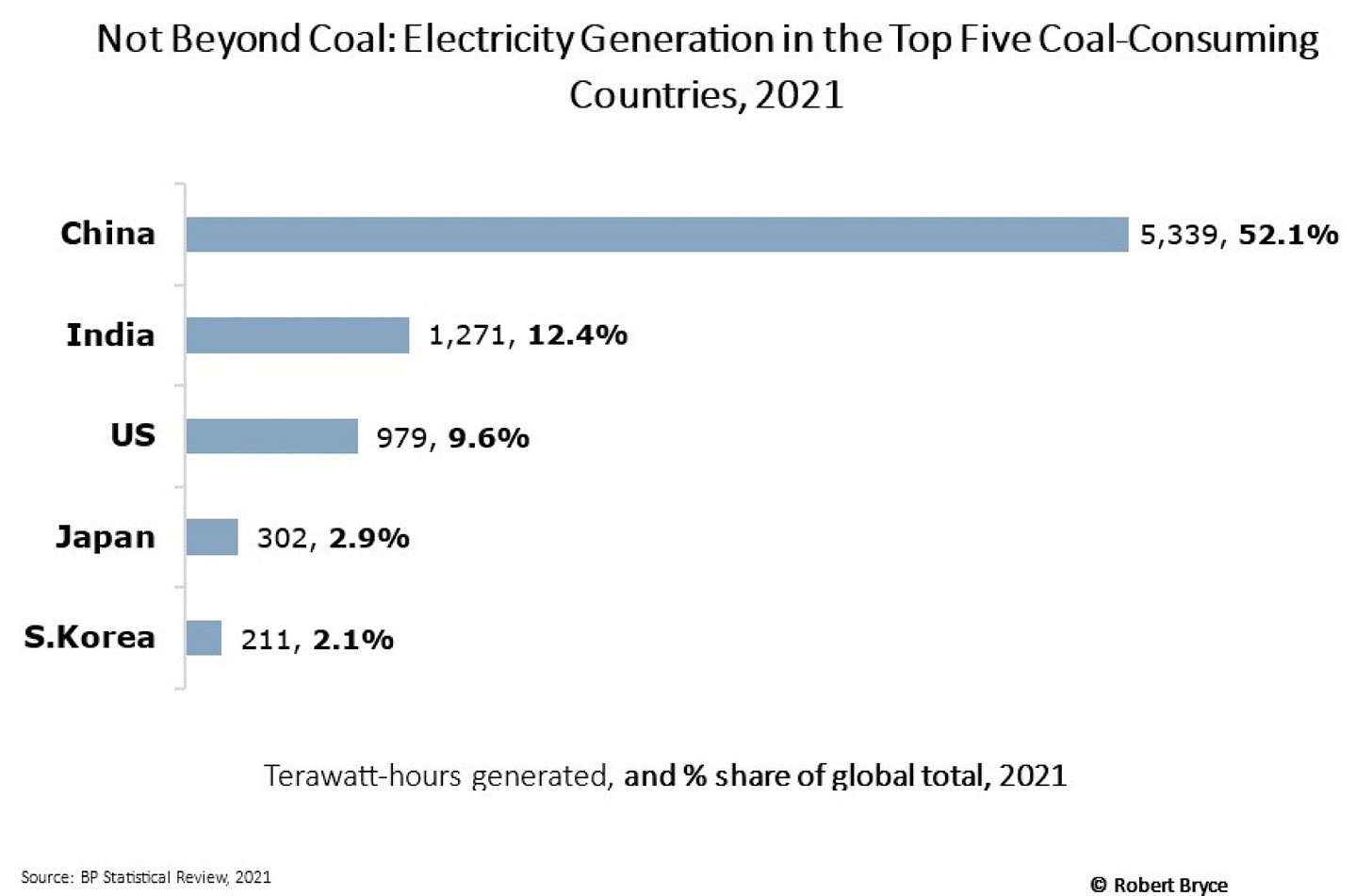

Figure 8

China consumes more coal (about 86 exajoules in 2021) than the rest of the world combined. China uses that coal to make steel and for industrial processes, but its biggest use is for power generation. As can be seen in the graphic above, China generated about 5,300 terawatt-hours of electricity from coal in 2021. That is about four times the amount generated by India and more than five times as much as the United States.

Although China accounts for the biggest share of global coal use, other countries are also increasing their use of coal. This is even true in Japan, the home of the Kyoto Protocol. Although the Japanese government has claimed that it will achieve net zero by 2050, Japanese utilities are currently building a new 1,300-megawatt coal-fired power plant near Kurihama called Yokosuka. The plant will have two ultra-supercritical generators and will be completed in 2024. Shikoku Electric Power is also building a 500-megawatt coal plant in Saijo. Like the Yokosuka plant, it will use ultra-supercritical technology, which is the most efficient way to burn coal. In addition, Japanese utilities are building eight new gas-fired power plants that will have a total capacity of 5.5 gigawatts.

Indeed, while the growth in global coal use is slowing, it will remain a key fuel for electricity generation for decades to come. In February 2023, Global Energy Monitor reported that China permitted about two new coal-fired power plants per week in 2022. The permitted plants will have “a staggering 106 gigawatts of new coal capacity... equivalent to 100 large coal-fired power plants.” The group also noted that permitted capacity quadrupled compared to 2021 and that “China has seen a rapid increase in electric peak loads...due to an increase in the prevalence of air conditioners and exceptionally intense heat waves. This is prompting an increase in coal power plant development.”

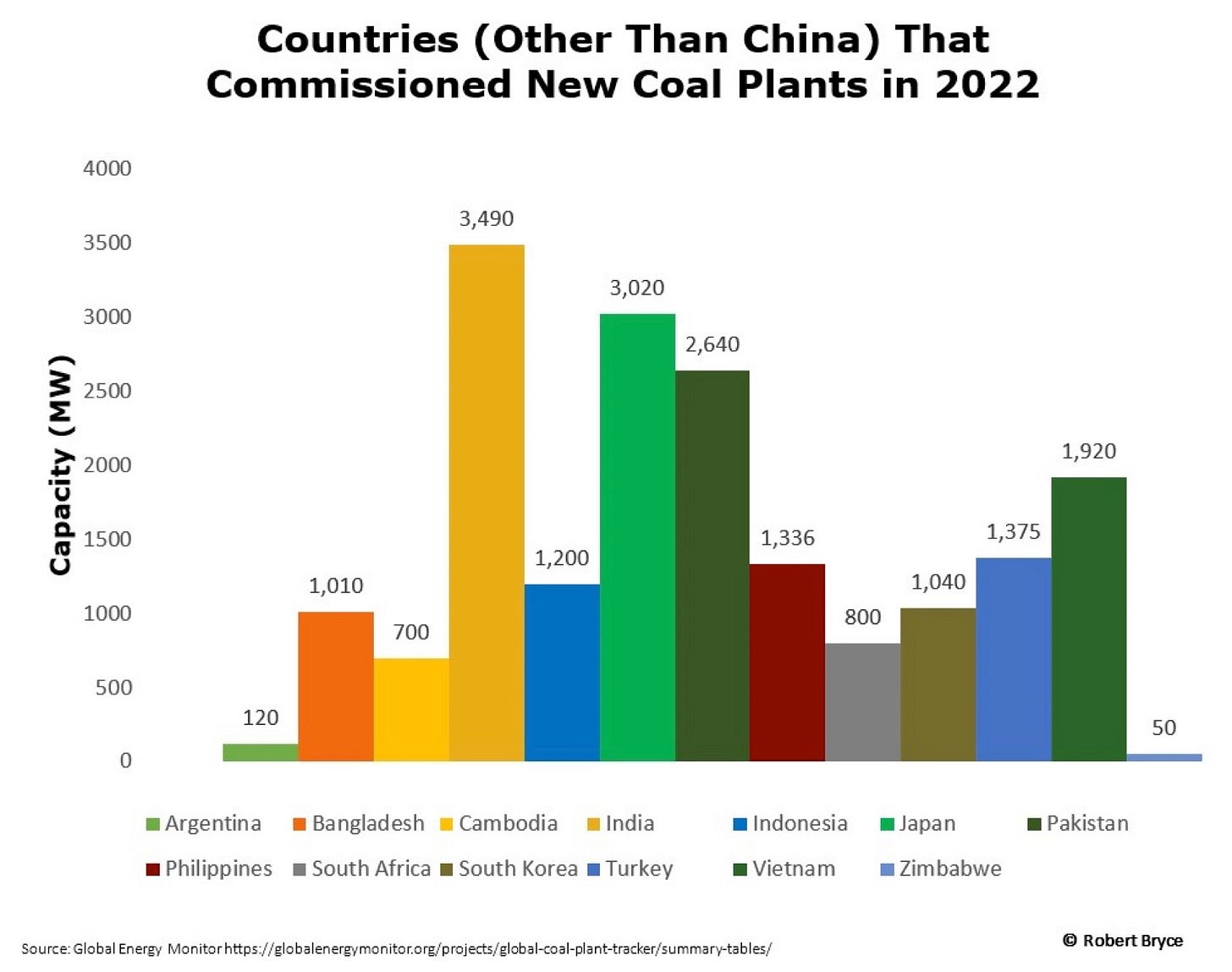

Figure 9

China accounted for 59% of the new coal-fired capacity that was brought online in 2022. But numerous other countries also commissioned new coal plants last year. According to Global Energy Monitor, Argentina, Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Japan, Pakistan, Philippines, Turkey, Vietnam, and Zimbabwe, all brought new coal-fired capacity online in 2022. As can be seen in the graphic above, those countries brought on nearly 19 gigawatts of new coal-fired capacity (China commissioned nearly 27 gigawatts). It should also be noted that of the 13 countries outside of China that brought on new coal-fired capacity in 2022, seven of them were in the Unplugged World.

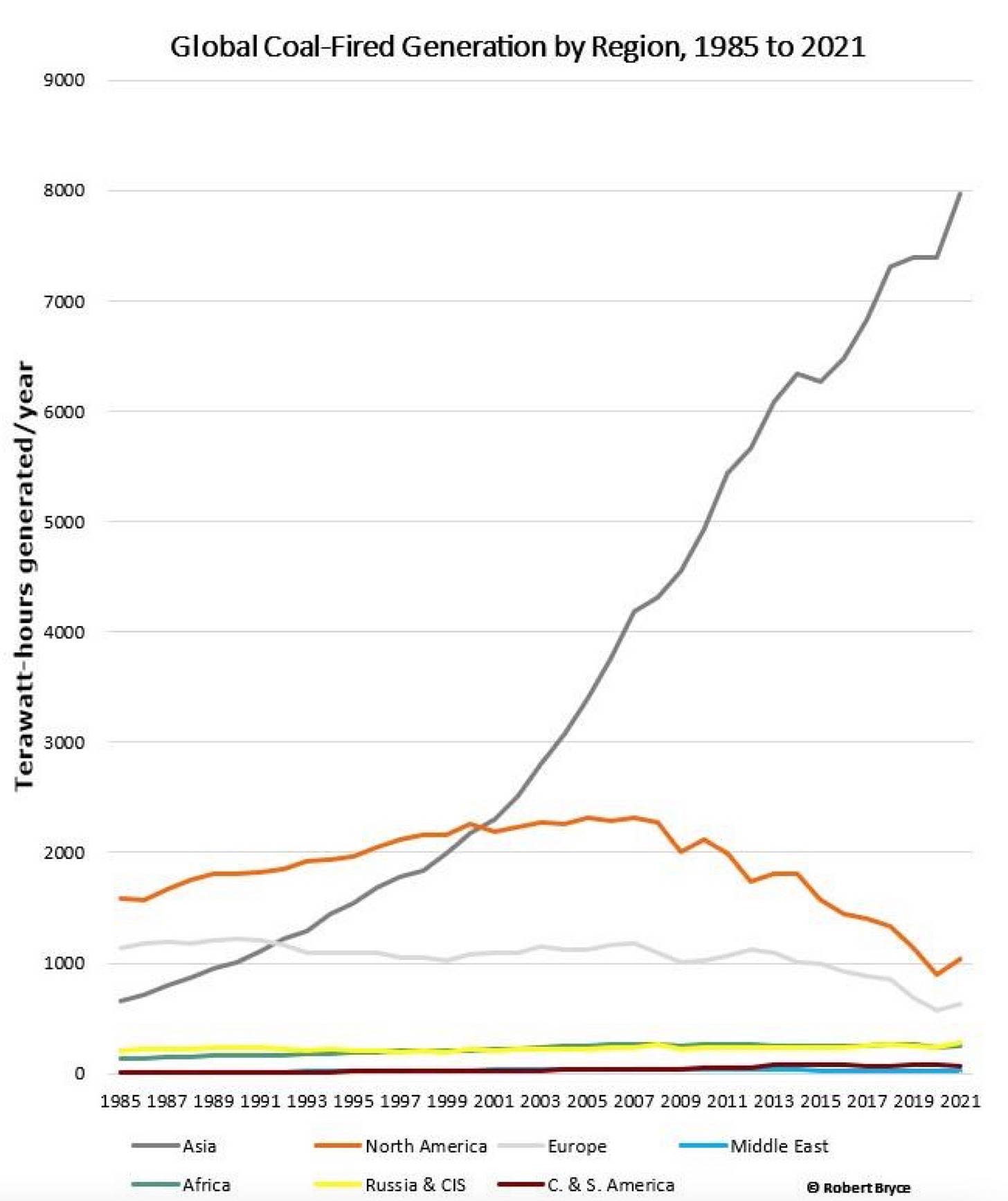

Figure 10

As can be seen in the graphic above, coal use in North America and Europe is falling. That is not the case in Asia.

It is essential to understand that industrial growth in Asia is driving much of that coal use as Western countries outsource manufacturing to China and other countries. Some of that fast growth in coal demand is occurring in Vietnam. On 14 June 2023, the Vietnam News Agency reported that the country’s state-owned coal miner, Vinacomin, will boost production by 15% this year so that it can increase supplies to the country’s power stations. The announcement followed several weeks of rolling blackouts in Vietnam that were wreaking havoc on big manufacturers that have been flocking to the country in recent years. In a 12th June article, Reuters quoted Hong Sun, the chairman of the Korean Chamber of Commerce in Vietnam, who said, “Many factories have had to suspend production due to severe power cuts, and the cuts are regular...This is a very serious problem for South Korean companies operating in Vietnam.”

Despite significant investments in hydro, solar, and wind, Vietnam is now getting about 60% of its juice from coal-fired power plants. Since 2009, Vietnam’s coal-fired electricity output has grown tenfold. More growth is on the way. Last year, according to Global Energy Monitor, Vietnam commissioned about 1,900 megawatts of new coal-fired capacity. That capacity will be used to help meet soaring demand. Over the past decade, electricity generation in Vietnam has been growing by an astounding 9% per year.

On 27 May 2023, James Kennemer, a consultant who helps companies access manufacturing capacity in Asia, wrote that Vietnam will soon become the “premier location” for manufacturing “shoes, furniture, garments, and electronics...The world’s largest brands are opening factories in Vietnam: Apple, Samsung, Nike, Adidas, LG, Foxconn, and others are examples of companies that have shut down Chinese factories in favour of Vietnamese factories.” He continued, saying Vietnam is “open for investment with little red tape” and that more factories are moving to the country, “especially after the U.S.-China trade war escalation.” He added that “big tech is moving into Vietnam...Apple recently started producing AirPods in Vietnam to cut down on import costs from China. Samsung has also moved into the country...The last few years have seen an increase of over 300% in electronics.” And here was the key line: the “average cost of hiring a factory employee in Vietnam is 1/3 those in China.”

The trends at work are obvious: in their never-ending search for cheap labour, multinational corporations are moving manufacturing from China to Vietnam. China industrialised by burning massive amounts of coal. Now, it is Vietnam’s turn.

Given the ongoing global dependence on coal-fired generation, how should policymakers be thinking of coal?

First, they should be working to assure that all coal plants are fitted with pollution-control devices to help reduce smog and air pollution. Second, they should be working to assure that all new coal plants are built with the highest possible efficiency so that grid operators are wringing the maximum amount of electricity possible from each ton of coal they burn. But recognising the ongoing need for coal only addresses part of the challenge. Bringing more poverty-stricken countries into modernity will also require overcoming the sticky problem of corruption.

Please click that ♡ button.

I was on the Financial Sense podcast last week with Simon Michaux, talking to Jim Puplava about energy demand, metals, minerals, and the foolishness of relying on Chinese supply chains. Check it out.

This week on the Power Hungry Podcast, I talked to my friend, Jeff Sandefer, the co-founder of Acton Academy, about why every child is a “genius,” and why the Acton model has gained so much traction.

Even more important in many parts of the world than release from the pump, the tub, and the stove is the release from the grindstone and the standing mortar and pestle. Preparing grains for cooking is laborious and takes as much as 5 hours a day. Thanks for this article.

Thanks for the great article.

I have personally worked for 4 years in Rwanda to extend the distribution network and connect entire villages to the national grid. It is a game changer when you have electricity.

As one Rwandan lady told me: “Now I can finally see the beauty of my village during the night”.