Nuclear Now?

Nuclear energy is gaining momentum, but big obstacles loom

On July 31, the Unit 3 reactor at Plant Vogtle began commercial operation. The milestone is a significant one for the U.S. nuclear sector. It’s the first new reactor to come online in the U.S. since 2016. The Unit 4 reactor is expected to come online later this year or early next year.

The addition of the Vogtle reactors to the American nuclear fleet is a welcome boost to a sector that’s desperate for traction. But the news from Vogtle is also bittersweet. Construction was expected to take four or five years. Instead, it took 11 years. The two units were supposed to cost $14 billion. Instead, they cost about $35 billion.

The completion of the reactors at Vogtle is among dozens of examples that nuclear energy is gaining steam both here in the U.S. and around the world. While it’s good to celebrate these wins, we need to take a sober look at nuclear energy and the challenges that lie ahead. I’ll focus on the three biggest ones: capital, fuel, and regulation.

Before going further, let me be clear: I am adamantly pro-nuclear and have been for more than a dozen years. My view is simple: If you are anti-carbon dioxide and anti-nuclear, you are pro-blackout. I am anti-blackout. I’m particularly anti-blackout since Winter Storm Uri left our home in Austin without power for two days in 2021. But it’s not enough to proclaim support for nuclear. We have to be clear-eyed about the many obstacles facing the sector.

Let me also be clear: many things are going right. Last year, after sustained activism by numerous pro-nuclear groups, California legislators voted to prevent the premature closure of the 2,250-megawatt Diablo Canyon Power Plant. This week, Wolverine Power Cooperative signed a power purchase agreement with Holtec International that could help rescue the Palisades Power Plant in Michigan from the wrecking ball.

This year, numerous nuclear companies have announced new investments, regulatory milestones, or contracts. The list of companies that are aiming to deploy cutting-edge reactors includes NuScale Power, X-Energy, Oklo, Kairos Power, Black Mesa Advanced Fission, Last Energy, Westinghouse, and others. In July, Ontario Power Generation announced a dramatic expansion of Canada’s nuclear fleet with an expansion of the world’s largest operating nuclear plant, Bruce Power. All across Europe, countries are returning to nuclear energy due to concerns about energy security and climate.

Public support for nuclear is increasing. In April, Gallup reported that 55% of Americans support nuclear energy, the highest percentage in a decade. Last year, Frankie Fenton released his pro-nuclear documentary, Atomic Hope. Earlier this year, Oliver Stone (along with Joshua Goldstein) released the pro-nuclear film, Nuclear Now, which is available on multiple streaming platforms. (In addition, Juice: Power, Politics, and The Grid, a five-part, pro-nuclear docuseries I am producing along with the film’s director, Tyson Culver, will be released in the fourth quarter. It will be distributed on YouTube and will be free. More details on that soon.)

Now back to the challenges. Let’s start with the most important one: money. The overwhelming majority of the money in the energy sector is being put into wind and solar, not nuclear.

There are plenty of examples to prove that point. The International Energy Agency recently published its “World Energy Investment 2023” report. As can be seen in the graphic above, which I created using numbers from the IEA report, global spending on renewables is ten times greater than the spending on nuclear energy and it has been that way for about a decade. The report has plenty of other sobering numbers. In 2023, global spending on nuclear will total $63 billion while spending on coal will total $148 billion. Spending on renewables will total some $659 billion while spending on upstream oil and gas will be about $508 billion.

Spending on nuclear in the U.S. is dwarfed by the amount of capital being lavished on wind, solar, EVs, and other forms of alt-energy. That can be seen in the graphic above, which was published this month by the Department of Energy’s Loan Program Office. While the individual numbers are not broken out, the image clearly shows that federal lending for “advanced nuclear,” a catch-all term that includes everything from small modular reactors to supply chains, is a fraction of the cash going to renewables, biofuels, offshore wind, EVs, hydrogen, and “advanced fossil.” (Whatever that is.)

Now to the fuel problem. I wrote about this issue in June, in “No U,” explaining that:

A looming shortage of enriched uranium and HALEU (short for high assay low enriched uranium) could derail the nuclear renaissance before it gets started. And that shortage will be particularly problematic for the United States, which operates the world’s biggest fleet of reactors and accounts for about 30% of global nuclear electricity generation.

This week, the Wall Street Journal reported that electric utilities “are on track to sign contracts for more uranium in 2023 than in any year since 2012.” In addition, the article cited the World Nuclear Association, which expects global nuclear generation capacity to expand by 75% between now and 2040. But all of that additional capacity hinges on getting uranium out of the ground and turning it into nuclear fuel.

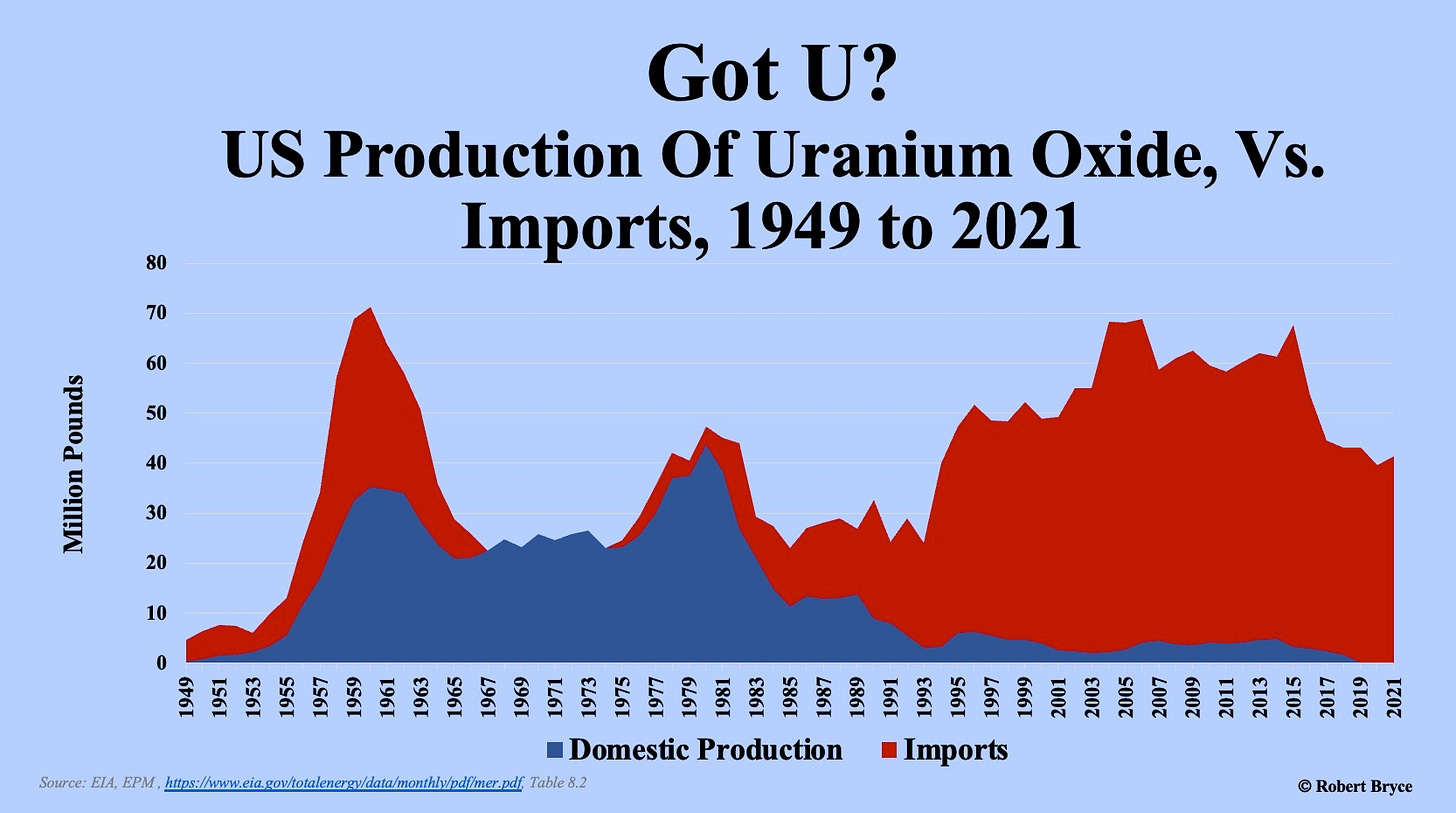

As can be seen in the graphic above, the U.S. nuclear sector used to be self-sufficient in uranium and nuclear fuel supplies. In 1980, the U.S. produced a record 43 million pounds of uranium oxide. Today, it isn’t producing any uranium oxide. Over the past four decades or so, the U.S. went from being the world’s biggest exporter of nuclear fuel to its biggest importer. And much of that fuel (about 14%) is coming from Russia, the world’s biggest enricher of uranium. About 46% of the world’s enrichment capacity is controlled by Russia.

In February, Centrus Energy, the only domestic producer licensed to produce HALEU, said that “A full-scale HALEU cascade, consisting of 120 individual centrifuge machines, with a combined capacity of approximately 6,000 kilograms of HALEU per year, could be brought online within about 42 months of securing the funding to do so.” But six metric tons won’t be nearly enough to meet demand. The Department of Energy estimates that more than 40 metric tons of HALEU will be needed by 2030. Last month, on the Power Hungry Podcast, Dan Poneman, the CEO of Centrus, told me the nuclear sector in the U.S. faces a chicken-and-egg problem. Utilities are not going to order a reactor that needs HALEU if they can’t be assured of having the fuel. But companies like Centrus, aren’t going to produce the HALEU if they don’t have a customer. The nuclear fuel challenge goes beyond enrichment. The U.S. will also need to ramp up domestic uranium mining.

The final issue is regulation, both on the international and domestic stages. Policymakers in countries that aspire to join the nuclear age will have to develop frameworks and standards for nuclear operations, fuel enrichment, waste handling, and disposal. Developing those frameworks, and the personnel to enforce them, will take years.

Here in the U.S., the industry has to overcome the bureaucracy at the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the Democratic Party’s reflexive opposition to nuclear energy. (As I wrote in 2020, the party has been anti-nuclear for nearly half a century.) While that stance has started to change, it hasn’t disappeared. In a September 7 piece in The Hill, Ted Nordhaus, the executive director of the Breakthrough Institute, expressed bewilderment at the Biden Administration’s nomination of Commissioner Jeff Baran for a third term on the NRC. Nordhaus wrote:

The Baran confirmation marks a crucible for Senate Democrats. Over two five-year terms on the Commission, Baran has been a reliable obstructionist, consistently opposing reasonable measures to modernize regulation of nuclear energy to value its benefits as a clean and reliable source of carbon-free energy. Over the same period, congressional Democrats have largely reversed their long-standing skepticism about nuclear energy, committing billions to commercialize a new generation of advanced nuclear reactors that promise to be smaller, safer, and less costly than today’s behemoth conventional reactors and directing the NRC to modernize its regulations to accommodate these new reactor technologies…But without new leadership on the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the promise of new nuclear technology is unlikely to be realized. The NRC has repeatedly failed to meet its own timeline for developing a new framework for licensing advanced reactors...With the first wave of those advanced reactor technologies now seeking licenses from the NRC, something will have to give. Baran, unfortunately, is not the man for this job.

Of course, the challenges facing nuclear go beyond capital, fuel, and regulation. We will also need to bolster supply chains that can provide the metal, pumps, and pipes that will be needed by the next generation of reactors. We will need training programs for welders, pipefitters, and engineers. In addition, in the U.S. we will need to reform electricity markets, abolish the subsidies for weather-dependent renewables, and incentivize the deployment of new nuclear plants. Congress will have to pass legislation to resolve the nuclear waste issue. And of course, policymakers will have to contend with the anti-industry industry, which continues to wage its idiotic war on nuclear energy. As I reported here last month, in “The Anti-Nuclear Industry Is A $2.3 Billion-Per-Year Racket,” anti-nuclear NGOs in the U.S. are outspending the pro-nuclear groups by about 14 to 1.

The punchline here is obvious: Reviving the global nuclear sector won’t be cheap, or easy, or quick. But there are many reasons for optimism. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has catalyzed a surge in interest in nuclear energy. A cadre of young, dedicated, pro-nuclear advocates has emerged here in the U.S. and in Europe. In addition, there are security reasons to push for nuclear energy. The U.S. and Europe must not cede global nuclear leadership to Russia and China, the latter of which is building 21 nuclear reactors. Meanwhile, with the Vogtle units now being completed, the U.S. has zero reactors under construction.

There is no path forward for reducing greenhouse gas emissions from the electric sector that doesn’t include a massive investment in nuclear energy. It’s time to get cracking.

Note: I corrected an error in the original graphic on global clean energy spending. The spending is in US$Billion. This year, spending on renewables will total about $659 billion while nuclear spending will be about $63 billion.

Please click that ♡ button. And don’t forget to subscribe and share.

Thanks.

The Plant Vogtle project has been a disaster for nuclear power in the U.S. What it demonstrated is that the U.S. no longer has the expertise to build nuclear power. Contrast Vogtle with Barakah in the United Arab Emirates. Barakah has four units that produce 1,400 megawatts each. The fourth unit is about to come online at the end of the year. The total cost was $24.4 billion. Vogtle built two units, 1,100 megawatts each, and spent more than $30 billion. The financial risk of nuclear power is so great that utility companies cannot and will not take it on. It is also hard for nuclear power to make money in the face of wind and solar operators who can afford to give their electricity away for free. They make so much from government subsidies that selling electricity is a sideline. A decade ago there was a genuine nuclear revival underway. Quite a number of projects were being pursued all around the U.S. because many sites here are licensed for multiple units but have not built all they are licensed for. Palo Verde is an example -- licensed for six units but only three have been built. The NRC has also licensed several advanced designs -- Vogue built pre-licensed AP1000 reactors -- so the regulatory hurdles have already been cleared, only the financing and construction risks remain. Sadly, these risks are enormous, as Vogtle demonstrated, and all the projects that were active a decade ago have been abandoned. It's going to require a huge change in policy by U.S. politicians and the now entrenched wind and solar interests are going to fight every step of the way. Our energy policy has descended into a gigantic mess, and it won't be easily extracted.

Why let unelected bureaucrats pick winners and losers using taxpayer money? What’s wrong with all energy sources competing on a cost/benefit basis?